Title screen of The Trap

Lucy Kelsall

Stephen Lambert

(Executive Producer)

| The Trap: What Happened to Our Dream of Freedom | |

|---|---|

Title screen of The Trap |

|

| Approx. run time | 180 min. (in three parts) |

| Genre | Documentary series |

| Written by | Adam Curtis |

| Directed by | Adam Curtis |

| Produced by | Adam Curtis Lucy Kelsall Stephen Lambert (Executive Producer) |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Original channel | BBC Two |

| Original run | 11 March 2007 – 25 March 2007 |

| No. of episodes | 3 |

| Preceded by | The Power of Nightmares |

The Trap: What Happened to Our Dream of Freedom is a BBC documentary series by English filmmaker Adam Curtis, well known for other documentaries including The Century of the Self and The Power of Nightmares. It began airing in the United Kingdom on BBC Two on 11 March 2007.[1]

The series consists of three one-hour programmes which explore the concept and definition of freedom, specifically, "how a simplistic model of human beings as self-seeking, almost robotic, creatures led to today's idea of freedom."[2]

Contents[hide] |

The series was originally entitled Cold Cold Heart and was scheduled for transmission in Autumn 2006. Although it is not known what caused the delay in transmission, nor the change in title,[3] it is known that the DVD release of Curtis's previous series The Power of Nightmares had been delayed due to problems with copyright clearance, caused by the high volume of archive soundtrack and film used in Curtis's characteristic montage technique.[improper synthesis?][4]

Another documentary series (title unknown) based on very similar lines—"examining the world economy during the 1990s"—was to have been Curtis's first BBC TV project on moving to the BBC's Current Affairs Unit in 2002, shortly after producing Century of the Self.[5]

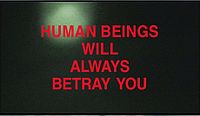

In this episode, Curtis examines the rise of game theory during the Cold War and the way in which its mathematical models of human behaviour filtered into economic thought. The programme traces the development of game theory with particular reference to the work of John Nash, who believed that all humans were inherently suspicious and selfish creatures that strategised constantly. Using this as his first premise, Nash constructed logically consistent and mathematically verifiable models, for which he won the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences, commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics. He invented system games reflecting his beliefs about human behaviour, including one he called "Fuck You Buddy" (later published as "So Long Sucker"), in which the only way to win was to betray your playing partner, and it is from this game that the episode's title is taken. These games were internally coherent and worked correctly as long as the players obeyed the ground rules that they should behave selfishly and try to outwit their opponents, but when RAND's analysts tried the games on their own secretaries, they instead chose not to betray each other, but to cooperate every time. This did not, in the eyes of the analysts, discredit the models, but instead proved that the secretaries were unfit subjects.

What was not known at the time was that Nash was suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, and, as a result, was deeply suspicious of everyone around him—including his colleagues—and was convinced that many were involved in conspiracies against him. It was this mistaken belief that led to his view of people as a whole that formed the basis for his theories. Footage of an older and wiser Nash was shown in which he acknowledges that his paranoid views of other people at the time were false.

Curtis examines how game theory was used to create the USA's nuclear strategy during the Cold War. Because no nuclear war occurred, it was believed that game theory had been correct in dictating the creation and maintenance of a massive American nuclear arsenal—because the Soviet Union had not attacked America with its nuclear weapons, the supposed deterrent must have worked. Game theory during the Cold War is a subject Curtis examined in more detail in the To The Brink of Eternity part of his first series, Pandora's Box, and he reuses much of the same archive material in doing so.

A separate strand in the documentary is the work of R.D. Laing, whose work in psychiatry led him to model familial interactions using game theory. His conclusion was that humans are inherently selfish, shrewd, and spontaneously generate strategems during everyday interactions. Laing's theories became more developed when he concluded that some forms of mental illness were merely artificial labels, used by the state to suppress individual suffering. This belief became a staple tenet of counterculture during the 1960s. Reference is made to the Rosenhan experiment, in which bogus patients, surreptitiously self-presenting at a number of American psychiatric institutions, were falsely diagnosed as having mental disorders, while institutions, informed that they were to receive bogus patients, "identified" numerous supposed imposters who were actually genuine patients. The results of the experiment were a disaster for American psychiatry, because they destroyed the idea that psychiatrists were a privileged elite able to genuinely diagnose, and therefore treat, mental illness.

All these theories tended to support the beliefs of what were then fringe economists such as Friedrich von Hayek, whose economic models left no room for altruism, but depended purely on self-interest, leading to the formation of public choice theory. In an interview, the economist James M. Buchanan decries the notion of the "public interest", asking what it is and suggesting that it consists purely of the self-interest of the governing bureaucrats. Buchanan also proposes that organisations should employ managers who are motivated only by money. He describes those who are motivated by other factors—such as job satisfaction or a sense of public duty—as "zealots".

As the 1960s became the 1970s, the theories of Laing and the models of Nash began to converge, producing a widespread popular belief that the state (a surrogate family) was purely and simply a mechanism of social control which calculatedly kept power out of the hands of the public. Curtis shows that it was this belief that allowed the theories of Hayek to look credible, and underpinned the free-market beliefs of Margaret Thatcher, who sincerely believed that by dismantling as much of the British state as possible—and placing former national institutions into the hands of public shareholders—a form of social equilibrium would be reached. This was a return to Nash's work, in which he proved mathematically that if everyone was pursuing their own interests, a stable, yet perpetually dynamic, society could result.

The episode ends with the suggestion that this mathematically modelled society is run on data—performance targets, quotas, statistics—and that it is these figures combined with the exaggerated belief in human selfishness that has created "a cage" for Western humans. The precise nature of the "cage" is to be discussed in the next episode.

The second episode reiterated many of the ideas of the first, but developed the theme that drugs such as Prozac and lists of psychological symptoms which might indicate anxiety or depression were being used to normalise behaviour and make humans behave more predictably, like machines.

This was not presented as a conspiracy theory, but as a logical (although unpredicted) outcome of market-driven self-diagnosis by checklist based on symptoms, but not actual causes, discussed in the previous programme.

People with standard mood fluctuations diagnosed themselves as abnormal. They then presented themselves at psychiatrist's offices, fulfilled the diagnostic criteria without offering personal histories, and were medicated. The alleged result was that vast numbers of Western people have had their behaviour and mentation modified by SSRI drugs without any strict medical necessity.

The Ax Fight—a famous anthropological study of the Yanomamo people of Venezuela by Tim Asch and Napoleon Chagnon—was re-examined and its strictly genetic-determinist interpretation called into question. Other researchers were called upon to verify Chagnon's conclusions and arrived at totally opposed opinions. The suggestion was raised that the presence of a film crew and the handing out of machetes to some, but not all, tribesmen might have caused them to 'perform' as they did. While being questioned by Curtis, Chagnon was so annoyed by this suggestion that he terminated the interview and walked out of shot, protesting under his breath.

Film of Richard Dawkins propounding his ultra-strict "selfish gene" analogy of life was shown, with the archive clips spanning two decades to emphasise how the severely reductionist ideas of programmed behaviour have been absorbed by mainstream culture. (Later, however, the documentary gives evidence that cells are able to selectively replicate parts of DNA dependent on current needs. According to Curtis such evidence detracts from the simplified economic models of human beings). This brought Curtis back to the economic models of Hayek and the game theories of Cold War. Curtis explains how, with the "robotic" description of humankind apparently validated by geneticists, the game theory systems gained even more hold over society's engineers.

The programme describes how the Clinton administration gave in to market theorists in the US and how New Labour in the UK decided to measure everything it could, the better to improve it, introducing such artificial and unmeasurable targets as:

It also introduced a rural community vibrancy index in order to gauge the quality of life in British villages and a birdsong index to check the apparent decline of wildlife.

In industry and the public services, this way of thinking led to a plethora of targets, quotas, and plans. It was meant to set workers free to achieve these targets in any way they chose. What these game-theory schemes did not predict was that the players, faced with impossible demands, would cheat.

Curtis describes how, in order to meet artificially inflated targets:

In a section called "The Death of Social Mobility", Curtis also describes how the theory of the free market was applied to education. With league tables of school performance published, the richest parents moved house to get their children into better schools. This caused house prices in the appropriate catchment areas to rise dramatically—thus excluding poorer parents who were left with the worst-performing schools. This is just one aspect of a more rigidly stratified society, which Curtis identifies in the way in which the incomes of the poorest (working class) Americans have actually fallen in real terms since the 1970s, while the incomes of the average (middle class) have increased slightly and those of the highest earners (upper class) have quadrupled. Similarly, babies in poorer areas in the UK are twice as likely to die in their first year as children from prosperous areas.

Curtis's narration concludes with the observation that the game theory/free market model is now undergoing interrogation by economists who suspect a more irrational model of behaviour is appropriate and useful. In fact, in formal experiments the only people who behaved exactly according to the mathematical models created by game theory are economists themselves, or psychopaths.

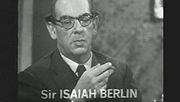

The final programme focussed on the concepts of positive and negative liberty introduced in the 1950s by Isaiah Berlin. Curtis briefly explained how negative liberty could be defined as freedom from coercion and positive liberty as the opportunity to strive to fulfill one's potential. Tony Blair had read Berlin's essays on the topic and wrote to him[7] in the late 1990s, arguing that positive and negative liberty could be mutually compatible. He never received a reply, as Berlin was on his death bed.

The programme began with a description of the Two Concepts of Liberty, claiming that it was Berlin's opinion that, since it lacked coercion, negative liberty was the 'safer' of the two. Curtis then explained how many political groups who sought their vision of freedom ended up using violence to achieve it.

For example the French revolutionaries wished to overthrow a monarchical system which they viewed as antithetical to freedom, but in so doing ended up with the Reign of Terror. Similarly, the Bolshevik revolutionaries in Russia, who sought to overthrow the old order and replace it with a society in which everyone was equal, ended up creating a totalitarian regime which used violence to achieve its ends.

Using violence, not simply as a means to achieve one's goals, but also as an expression of freedom from Western bourgeois norms, was an idea developed by African revolutionary Frantz Fanon. He developed it from the Existentialist ideology of Jean-Paul Sartre, who argued that terrorism was a "terrible weapon but the oppressed poor have no others." [8]. These views were expressed, for example, in the revolutionary film The Battle of Algiers.

This programme also explored how economic freedom had been used in Russia and the problems this had introduced. A set of policies known as "shock therapy" were brought in mainly by outsiders, which had the effect of destroying the social safety net that existed in most other western nations and Russia. In the latter, the sudden removal of e.g. the subsidies for basic goods caused their prices to rise enormously, making them hardly affordable for ordinary people. An economic crisis escalated during the 1990s and some people were paid in goods rather than money. Yeltsin was accused by his parliamentary deputies of "economic genocide", due to the large numbers of people now too poor to eat. Yeltsin responded to this by removing parliament's power and becoming increasingly autocratic. At the same time, many formerly state-owned industries were sold to private businesses, often at a fraction of their real value. Ordinary people, often in financial difficulties, would sell shares, which to them were worthless, for cash, without appreciating their true value. This ended up with the rise of the Oligarchs—super-rich businessmen who attributed their rise to the sell offs of the '90s. It resulted in a polarisation of society into the poor and ultra-rich, and indirectly led to a more autocratic style of government under Vladimir Putin, which, while less free, promised to provide people with dignity and basic living requirements.

There was a similar review of post-war Iraq, in which an even more extreme "shock therapy" was employed—the removal from government of all Ba'ath party employees and the introduction of economic models which followed the simplified economic model of human beings outlined in the first two programmes—this had the result of immediately disintegrating Iraqi society and the rise of two strongly autocratic insurgencies, one based on Sunni-Ba'athist ideals and another based on revolutionary Shi'a philosophies.

Curtis also looked at the neo-conservative agenda of the 1980s. Like Sartre, they argued that violence would sometimes be necessary to achieve their goals, except they wished to spread what they described as democracy. Curtis quoted General Alexander Haig then US Secretary of State, as saying that "some things were worth fighting for". However, Curtis argued, although the version of society espoused by the neo-conservatives made some concessions towards freedom, it did not offer true freedom. The neo-conservatives were ardent supporters of the Augusto Pinochet regime in Chile which used violence to crush opponents in a virtual police state.

The neo-conservatives also took a strong line against the Sandinistas—a political group in Nicaragua—who Reagan argued were accepting help from the Soviets and posed a real threat to American security. The truth was that the Sandinistas posed no real military threat to the US, and a disinformation campaign was started against them painting them as accessories of the Soviets. The Contras, who were a proxy army fighting against the Sandinistas, were—according to US propaganda—valiantly fighting against the evil of Communism. In reality, argued Curtis, they were using all manner of techniques, including the torture, rape and murder of civilians. The CIA funded the Contras by allegedly flying in cocaine into the United States, as financing the Contras directly would have been illegal.

However such policies did not always result in the achievement of neo-conservative aims and occasionally threw up genuine surprises. Curtis examined the Western-backed government of the Shah in Iran, and how the mixing of Sartre's positive libertarian ideals with Shia religious philosophy led to the revolution which overthrew it. Having previously been a meek philosophy of acceptance of the social order, in the minds of revolutionaries such as Ali Shariati and Ayatollah Khomeini, Revolutionary Shia Islam became a meaningful force to overthrow tyranny.

The programme reviewed the Blair government and its role in achieving its vision of a stable society. In fact, argued Curtis, the Blair government had created the opposite of freedom, in that the type of liberty it had engendered wholly lacked any kind of meaning. Its military intervention in Iraq had provoked terrorist actions in the UK and these terrorist actions were in turn used to justify restrictions of liberty.

In essence, the programme suggested that following the path of negative liberty to its logical conclusions, as governments have done in the West for the past 50 years, resulted in a society without meaning populated only by selfish automatons, and that there was some value in positive liberty in that it allowed people to strive to better themselves.

The closing minutes directly state that if western humans were ever to find their way out of the "trap" described in the series, they would have to realise that Isaiah Berlin was wrong and that not all attempts at creating positive liberty necessarily ended in coercion and tyranny.

Economist Max Steuer criticised the documentary for "romanticis[ing] the past while misrepresenting the ideas it purports to explain"; for example Curtis suggested that the work of Buchanan and others on public choice theory made Government officials wicked and selfish, rather than simply providing an account of what happened.[9]

In the New Statesman, Rachel Cooke argued that the series didn't make a coherent argument.[10] She said that while she was glad Adam Curtis made provocative documentaries he was as much of a propagandist as those he opposes.[10]

While commending the series, Radio Times stated that The Trap's subject matter was not ideal for its 21:00 Sunday time slot on the minority BBC Two. This placed the three episodes against Castaway 2007 on BBC One, the drama Fallen Angel, the first two of a series of high-profile Jane Austen adaptations on ITV1, and season six of 24 on Sky One. However, the series secured a consistent share of the viewing audience throughout its run:

1. "Fuck You Buddy" (11 March 2007) ~ 1.4 million viewers; 6% audience share

2. "The Lonely Robot (18 March 2007) ~ 1.3 million viewers; 6% audience share

3. "We Will Force You To Be Free" (25 March 2007) ~ 1.3 million viewers; 6% audience share

It Felt Like a Kiss is an olfactory-audiovisual promenade-style theatre production, first performed between 2 and 19 July 2009 as part of the second Manchester International Festival, co-produced with the BBC[1]. Themed on "how power really works in the world"[2], it is a collaboration between film-maker Adam Curtis and the Punchdrunk theatre company, with original music composed by Damon Albarn and performed by the Kronos Quartet. The visitor is immersed in sets based on archive footage from Bagdad, 1963; New York, 1964; Moscow, 1959; in the Amygdala, 1959-69; and Kinshasa, 1960. The title is taken from The Crystals' 1962 song "He Hit Me (It Felt Like A Kiss)", written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King.[3]

Contents[hide] |

The production was staged at Quay House, in the disused former offices of the National Probation Service on Quay Street, central Manchester. The production ran between 2 and 19 July 2009, as part of the second Manchester International Festival.

| “ | Imagine walking into a disused building. You find yourself inside a film. It is a ghost story where unexpected forces, veiled by the American Dream, come out from the dark to haunt you… | ” |

|

— [3]

|

The film and event makes extensive use of archive footage. Upon arrival at the event groups of nine[4] visitors are taken to a darkened sixth floor. The 54 minute film (available for a limited time online in the UK)[5] is only a small section ("the film club") of the event.[6]

Featured in the story are Eldridge Cleaver, Doris Day, Little Eva, Philip K Dick, Enos (a chimpanzee sent into space), Sidney Gottlieb, Rock Hudson, Saddam Hussain, Richard Nixon, Lee Harvey Oswald, Lou Reed, Mobutu Sese Seko, B F Skinner, Phil Spector, Tina Turner and Frank Wisner.

| “ | I wanted to do a film about what it actually felt like to live through that time ... Where you could see the roots of the uncertainties we feel today, the things they did out on the dark fringes of the world that they didn't really notice at the time, which would then come back to haunt us. | ” |

|

— Adam Curtis[7]

|

As with all Curtis' work, the Helvetica typeface is prominently featured, but unlike his other works, it does not feature narration.

The production started life as an experimental film by Adam Curtis, commissioned by the BBC. Curtis approached Felix Barrett of the Punchdrunk theatre company, with the proposal that a production could be created "as though the audience were walking through the story of the film".[8]

The film was shown to Damon Albarn, already associated with the Manchester International Festival through the productions Demon Days Live in 2006 and Monkey: Journey to the West in 2007. He agreed to write a score for the production, which was then recorded by the San Francisco-based Kronos Quartet.

According to Adam Curtis the production is "the story of an enchanted world that was built by American power as it became supreme...and how those living in that dream world responded to it".[8] He has also said; "it’s trying to show to you that the way you feel about yourself and the way you feel about the world today is a political product of the ideas of that time”.[9]

"The politics of our time," according to Curtis, "are deeply embedded in the ideas of individualism...but it's not the be-all-and-end-all...the notion that you only achieve your true self if your dreams, your desires, are satisfied...it's a political idea".[7]

Felix Barrett has stated that the production was influenced by his love of ghost trains and haunted houses, and by the idea of blurring fiction with reality: "It takes the idea of the viewer as voyeur and asks at what point are you watching, inside or even starring in the film".[8]

The development of new techniques of interrogation by "everyone over Level 7" in the CIA during the 1960s is a theme of the production, and the suggestibility of human beings is something that the production seeks to highlight.[citation needed]

See It Felt Like A Kiss (Spotify))

| The Power of Nightmares | |

|---|---|

title screen |

|

| Format | Documentary series |

| Directed by | Adam Curtis |

| Narrated by | Adam Curtis |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom |

| Language(s) | English |

| No. of episodes | 3 |

| Production | |

| Producer(s) | Adam Curtis Executive Producer Stephen Lambert |

| Running time | 180 minutes |

| Broadcast | |

| Original channel | BBC Two |

| Original run | 20 October – 3 November 2004 |

The Power of Nightmares, subtitled The Rise of the Politics of Fear, is a BBC documentary film series, written and produced by Adam Curtis. Its three one-hour parts consist mostly of a montage of archive footage with Curtis's narration. The series was first broadcast in the United Kingdom in late 2004 and has subsequently been broadcast in multiple countries and shown in several film festivals, including the 2005 Cannes Film Festival.

The films compare the rise of the Neo-Conservative movement in the United States and the radical Islamist movement, making comparisons on their origins and claiming similarities between the two. More controversially, it argues that the threat of radical Islamism as a massive, sinister organised force of destruction, specifically in the form of al-Qaeda, is a myth perpetrated by politicians in many countries—and particularly American Neo-Conservatives—in an attempt to unite and inspire their people following the failure of earlier, more utopian ideologies.

The Power of Nightmares has been praised by film critics in both Britain and the United States. Its message and content have also been the subject of various critiques and criticisms from conservatives and progressives.

Contents[hide] |

|

|

|

|

Paul Wolfowitz and Ayman al-Zawahiri, featured

representatives of Neo-Conservatism and Islamism respectively. |

||

The first part of the series explains the origin of Islamism and Neo-Conservatism. It shows Egyptian civil servant Sayyid Qutb, depicted as the founder of modern Islamist thought, visiting the U.S. to learn about the education system, but becoming disgusted with what he saw as a corruption of morals and virtues in western society through individualism. When he returns to Egypt, he is disturbed by westernisation under Gamal Abdel Nasser and becomes convinced that in order to save society it must be completely restructured along the lines of Islamic law while still using western technology. He also becomes convinced that this can only be accomplished through the use of an elite "vanguard" to lead a revolution against the established order. Qutb becomes a leader of the Muslim Brotherhood and, after being tortured in one of Nasser's jails, comes to believe that western-influenced leaders can justly be killed for the sake of removing their corruption. Qutb is executed in 1966, but he inspires the future mentor of Osama bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, to start his own secret Islamist group. Inspired by the 1979 Iranian revolution, Zawahiri and his allies assassinate Egyptian president Anwar Al Sadat, in 1981, in hopes of starting their own revolution. The revolution does not materialise, and Zawahiri comes to believe that the majority of Muslims have been corrupted by their western-inspired leaders and thus may be legitimate targets of violence if they do not join him.

At the same time in the United States, a group of disillusioned liberals, including Irving Kristol and Paul Wolfowitz, look to the political thinking of Leo Strauss after the perceived failure of President Johnson's "Great Society". They come to the conclusion that the emphasis on individual liberty was the undoing of the plan. They envisioned restructuring America by uniting the American people against a common evil, and set about creating a mythical enemy. These factions, the Neo-Conservatives, came to power under the Reagan administration, with their allies Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, and work to unite the United States in fear of the Soviet Union. The Neo-Conservatives allege the Soviet Union is not following the terms of disarmament between the two countries, and, with the investigation of "Team B", they accumulate a case to prove this with dubious evidence and methods. President Reagan is convinced nonetheless.[1]

In the second episode, Islamist factions, rapidly falling under the more radical influence of Zawahiri and his rich Saudi acolyte Osama bin Laden, join the Neo-Conservative-influenced Reagan Administration to combat the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan. When the Soviets eventually pull out and when the Eastern Bloc begins to collapse in the late 1980s, both groups believe they are the primary architects of the "Evil Empire's" defeat. Curtis argues that the Soviets were on their last legs anyway, and were doomed to collapse without intervention.

However, the Islamists see it quite differently, and in their triumph believe that they had the power to create 'pure' Islamic states in Egypt and Algeria. However, attempts to create perpetual Islamic states are blocked by force. The Islamists then try to create revolutions in Egypt and Algeria by the use of terrorism to scare the people into rising up. However, the people are terrified by the violence and the Algerian government uses their fear as a way to maintain power. In the end, the Islamists declare the entire populations of the countries as inherently contaminated by western values, and finally in Algeria turn on each other, each believing that other terrorist groups are not pure enough Muslims either.

In America, the Neo-Conservatives' aspirations to use the United States military power for further destruction of evil are thrown off track by the ascent of George HW Bush to the presidency, followed by the 1992 election of Bill Clinton leaving them out of power. The Neo-Conservatives, with their conservative Christian allies, attempt to demonise Clinton throughout his presidency with various real and fabricated stories of corruption and immorality. To their disappointment, however, the American people do not turn against Clinton. The Islamist attempts at revolution end in massive bloodshed, leaving the Islamists without popular support. Zawahiri and bin Laden flee to the sufficiently safe Afghanistan and declare a new strategy; to fight Western-inspired moral decay they must deal a blow to its source: the United States.[2]

The final episode addresses the actual rise of al-Qaeda. Curtis argues that, after their failed revolutions, bin Laden and Zawahiri had little or no popular support, let alone a serious complex organisation of terrorists, and were dependent upon independent operatives to carry out their new call for jihad. The film instead argues that in order to prosecute bin Laden in absentia for the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings, US prosecutors had to prove he was the head of a criminal organisation responsible for the bombings. They find a former associate of bin Laden, Jamal al-Fadl, and pay him to testify that bin Laden was the head of a massive terrorist organisation called "al-Qaeda". With the September 11th attacks, Neo-Conservatives in the new Republican government of George W. Bush use this created concept of an organisation to justify another crusade against a new evil enemy, leading to the launch of the War on Terrorism.

After the American invasion of Afghanistan fails to uproot the alleged terrorist network, the Neo-Conservatives focus inwards, searching unsuccessfully for terrorist sleeper cells in America. They then extend the war on "terror" to a war against general perceived evils with the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The ideas and tactics also spread to the United Kingdom where Tony Blair uses the threat of terrorism to give him a new moral authority. The repercussions of the Neo-Conservative strategy are also explored with an investigation of indefinitely-detained terrorist suspects in Guantanamo Bay, many allegedly taken on the word of the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance without actual investigation on the part of the United States military, and other forms of "preemption" against non-existent and unlikely threats made simply on the grounds that the parties involved could later become a threat. Curtis also makes a specific attempt to allay fears of a dirty bomb attack, and concludes by reassuring viewers that politicians will eventually have to concede that some threats are exaggerated and others altogether devoid of reality.[3]

Adam Curtis originally intended to create a film about conflict within the conservative movement between the ideologies of Neo-Conservative "elitism" and more individualist libertarian factions. During his research into the conservative movement, however, Curtis first discovered what he saw as similarities in the origins of the Neo-Conservative and Islamist ideologies. The topic of the planned documentary shifted to these latter two ideologies while the libertarian element was eventually phased out.[4] Curtis first pitched the idea of a documentary on conservative ideology in 2003 and spent six months compiling the films.[5][6] The final recordings for the three parts were made on 10 October, 19 October and 1 November 2004.[7][8][9]

The film uses a montage of various stock footage from the BBC archives, often used for ironic or humorous effect, over which Curtis narrates.[4][5] Curtis has credited James Mossman as the inspiration for his montage technique, which he first employed for the 1992 series Pandora's Box,[10] while his use of humour has been credited to his first work with television as a talent scout for That's Life![5] He has also compared the entertainment format of his films to the American Fox News channel, claiming the network has been successful because of "[their viewers] really enjoying what they're doing".[4]

To help drive his points, Curtis includes interviews with various political and intellectual figures. In the first two films, former Arms Control and Disarmament Agency member Anne Cahn and former American Spectator writer David Brock accuse the Neo-Conservatives of knowingly using false evidence of wrongdoing in their campaigns against the Soviet Union and President Bill Clinton.[1][2] Jason Burke, author of Al-Qaeda: Casting a Shadow of Terror, comments in The Shadows in the Cave on the failure to expose a massive terrorist network in Afghanistan.[3] Additional interviews with major figures are added to drive the film's narrative. Neo-Conservatives William and Irving Kristol, Richard Pipes and Richard Perle all appear to chronicle the Neo-Conservative perspective of the film's subject.[1][3] The history of Islamism is discussed by the Institute of Islamic Political Thought's Azzam Tamimi, political scientist Roxanne Euben and Islamist Abdulla Anas.[1][2]

The film's soundtrack includes at least two pieces from the films of John Carpenter, whom Curtis credited as inspiration for his soundtrack arrangement techniques,[10] as well as tracks from Brian Eno's Another Green World. There is also music by composers Charles Ives and Ennio Morricone, while Curtis has credited the industrial band Skinny Puppy for the "best" samples in the films.[11]

The Power of Nightmares was first aired in three consecutive weeks on BBC 2 in 2004 in the United Kingdom, beginning with Baby it's Cold Outside on 20 October, The Phantom Victory on 27 October and The Shadows in the Cave on 3 November, although the murder of Kenneth Bigley led the BBC to curtail their advertising prior to its airing.[7][8][9][12] It was rebroadcast, in January 2005, over three days, with the third film updated to take note of the Law Lords ruling from the previous December that detaining foreign terrorist suspects without trial was illegal.[13]

In May 2005, the film was screened in a 2½ hour edit at the Cannes Film Festival out of competition.[14] Pathé purchased distribution rights for this cut of the film.[6]

As of 1 January 2008, the film has yet to be aired in the United States. Curtis has commented on this failure:

Something extraordinary has happened to American TV since September 11. A head of the leading networks who had better remain nameless said to me that there was no way they could show it. He said, 'Who are you to say this?' and then he added, 'We would get slaughtered if we put this out.' When I was in New York I took a DVD to the head of documentaries at HBO. I still haven't heard from him.[6]

Although the series has not been shown on U.S. television, its three episodes were shown in succession, on 26 February 2005, as part of the True/False Film Festival in Columbia, Missouri, with a personal appearance by Curtis.[15][16] It has also been featured at the 2006 Seattle International Film Festival and the San Francisco International Film Festival, with the latter awarding Curtis their Persistence of Vision Award.[17][18][19] The film was also screened at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York, and had a brief theatrical run in New York City during 2005.[20][21]

The films were first aired by CBC in Canada in April 2005, and again in July 2006.[22] The Australian channel SBS had originally scheduled to air the series in July 2005, but it was cancelled, reportedly in light of the London bombings of 7 July.[23][24] It was ultimately aired in December, followed by Peter Taylor's The New Al-Qaeda under the billing of a counter-argument to Curtis.[25]

In April 2005, Curtis expressed interest in an official DVD release due to a significant demand by viewers, but noted that his usual montage technique created serious legal problems with getting such a release secured.[26] An unofficial DVD release was made in the quarterly DVD magazine Wholphin over a period of three issues.[27][28][29]

The Power of Nightmares received generally favourable reviews from critics.[30] Rotten Tomatoes reported that 86% of critics gave the film positive write-ups, with an average score of 8.1/10, based upon a sample of seven reviews.[31] At Metacritic, which assigns a normalised rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film received an average score of 78, based on six reviews.[30] Entertainment Weekly described the film as "a fluid cinematic essay, rooted in painstakingly assembled evidence, that heightens and cleanses your perceptions" while Variety called it "a superb, eye-opening and often absurdly funny deconstruction of the myths and realities of global terrorism".[32][33] The San Francisco Chronicle had an equally enthusiastic view of the film and likened it to "a brilliant piece in the Atlantic Monthly that's (thankfully) come to cinematic life".[34] The New York Times had a more skeptical review, unimpressed by efforts to compare attacks on Bill Clinton by American conservatives with Islamist revolutionary activities, claiming (in a review by literary and film critic A. O. Scott) that "its understanding of politics, geo- and national, can seem curiously thin"[21]. In May 2005, Adam Curtis was quoted as saying that 94% of e-mails to the BBC in response to the film were supportive.[6]

The film was awarded a BAFTA in the category of "Best Factual Series" in 2005.[35] Additional awards were given by the Director's Guild of Great Britain and the Royal Television Society.[36][37]

Progressive observers were particularly pleased with the film. Common Dreams had a highly positive response to the film and compared it to the "red pill" of the Matrix series, a comparison Curtis has apparently appreciated.[26][38] Commentary in the Village Voice was also mostly favorable, noting: "As partisan filmmaking it is often brilliant and sometimes hilarious - a superior version of Syriana."[39] The Nation, while offering a detailed critique on the film's content, said of the film itself "[it] is arguably the most important film about the 'war on terrorism' since the events of September 11".[40]

Among conservative and neoconservative critics in the United States, The Power of Nightmares has been described as "conspiracy theory", anti-American or both. David Asman of FoxNews.com said, "We wish we didn't have to keep presenting examples of how the European media have become obsessively anti-American. But they keep pushing the barrier, now to the point of absurdity."[41] His views were shared by commentator Clive Davis, concluding his commentary on the film for National Review with "British producers, hooked on Chomskyite visions of 'Amerika' as the fount of all evil, are clearly not interested in even beginning to dig for the truth".[42] Other observers variously described the films as pushing a conspiracy theory. Davis and British commentator David Aaronovitch both explicitly labelled the film's message as a conspiracy theory, with the latter saying of Curtis "his argument is as subtle as a house-brick".[42][43] Attacks in this vein continued after the 7 July 2005 London bombings, with CBN referencing the film as a source for claims by the "British left" that "the U.S. War on Terror was a fraud" and the Australia Israel & Jewish Affairs Council calling it "the loopiest, most extreme antiwar documentary series ever sponsored by the BBC".[24][44] In The Shadows in the Cave, Curtis stressed that he did not discount the possibility of any terrorist activity taking place, but that the threat of terrorism had been greatly exaggerated.[3] He responded to accusations of creating a conspiracy theory that he believes that the alleged use of fear as a force in politics is not the result of a conspiracy but rather the subjects of the film "have stumbled on it".[26]

Peter Bergen, writing for The Nation, offered a detailed critique of the film. Bergen wrote that even if al-Qaeda is not as organised as the Bush Administration stresses, it is still a very dangerous force due to the fanaticism of its followers and the resources available to bin Laden. On Curtis's claim that al-Qaeda was a creation of neo-conservative politicians, Bergen said: "This is nonsense. There is substantial evidence that Al Qaeda was founded in 1988 by bin Laden and a small group of like-minded militants, and that the group would mushroom into the secretive, disciplined organisation that implemented the 9/11 attacks."[45] Bergen further claimed that Curtis's arguments serve as a defence of Bush's failure to capture bin Laden in the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan and his ignoring warnings of a terror attack prior to September 11.[46]

Additional issues have been raised over Curtis's depiction of the Neo-Conservatives. Davis's article in National Review showed his displeasure with Curtis's depiction of Leo Strauss, claiming, "In Curtis's world, it is Strauss, not Osama bin Laden, who is the real evil genius."[42] Peter Bergen claimed the film exaggerated the influence of Strauss over Neo-Conservatism, crediting the political philosophy more to Albert Wohlstetter.[47] A 2005 review on Christopher Null's Filmcritic.com took issue with The Phantom Victory 's retelling of the attacks on Bill Clinton, crediting these more to the American Religious Right than the "bookish university types" of the Neo-Conservative movement.[48]

Daniel Pipes, a conservative American political commentator and son of Richard Pipes who was interviewed in the film, wrote that the film dismisses the threat posed by Communism to the United States as, in Pipes words, "only a scattering of countries that had harmless Communist parties, who could in no way threaten America." Pipes noted that the film adopts this conclusion without mentioning the Comintern, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Klaus Fuchs or Igor Gouzenko.[49]

There are also allegations of omissions in the history described by the film. The absence of discussion of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was noticed by observers.[21][39] Davis claimed that Leo Strauss's ideas had been formed by his experiences in Germany during the Weimar Republic and alleged the film's failure to mention this was motivated by a wish to display Strauss as concerned with American suburban culture, like Qutb.[42]

Media Lens criticised the film for failing to explore the role of big business in the situation it described.[50]

After its release, The Power of Nightmares received multiple comparisons to Fahrenheit 9/11, American film-maker Michael Moore's 2004 critique on the first four years of George W. Bush's presidency of the United States. The Village Voice directly named The Power of Nightmares as "the most widely discussed docu agitprop since Fahrenheit 9/11".[39] The Nation and Variety both gave comments ranking Curtis's film superior to Fahrenheit and other political documentaries in various fields; the former cited Curtis's work being more "intellectually engaging" and "historically probing" while the latter cited "balance, broad-mindedness and sense of historical perspective".[33][40] Moore's work has also been used as a point of comparison by conservative critics of Curtis.[42]

Curtis has attempted to distinguish his work from Moore's film, dismissing him as "a political agitprop film-maker".[6]

| The Century of the Self | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Adam Curtis |

| Produced by | Adam

Curtis Lucy Kelsall Stephen Lambert (executive producer) |

| Written by | Adam Curtis |

| Starring | Sigmund

Freud Edward Bernays Werner Erhard Jerry Rubin Tony Blair Bill Clinton Robert Reich Wilhelm Reich Martin S. Bergmann Adam Curtis |

| Music by | Brahms Symphony No. 3 What a Wonderful World |

| Cinematography | David Barker William Sowerby |

| Distributed by | BBC Four |

| Release date(s) | 2002 |

| Running time | 240 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

The Century of the Self is a British television documentary film by Adam Curtis. It was first screened in the UK in four parts in 2002.

Contents[hide] |

"This series is about how those in power have used Freud's theories to try and control the dangerous crowd in an age of mass democracy." - Adam Curtis' introduction to the first episode.

|

|

This article does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2009) |

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, changed the perception of the human mind and its workings. His influence on the twentieth century is generally considered profound. The series describes the ways public relations and politicians have utilized Freud's theories during the last 100 years for the "engineering of consent".

Freud himself and his nephew Edward Bernays, who was the first to use psychological techniques in public relations, are discussed. Freud's daughter Anna Freud, a pioneer of child psychology, is mentioned in the second part, as is one of the main opponents of Freud's theories, Wilhelm Reich, in the third part.

Along these general themes, The Century of the Self asks deeper questions about the roots and methods of modern consumerism, representative democracy and its implications. It also questions the modern way we see ourselves, the attitude to fashion and superficiality.

The business and, increasingly, the political world uses psychological techniques to read and fulfill our desires, to make their products or speeches as pleasing as possible to us. Curtis raises the question of the intentions and roots of this fact. Where once the political process was about engaging people's rational, conscious minds, as well as facilitating their needs as a society, the documentary shows how by employing the tactics of psychoanalysis, politicians appeal to irrational, primitive impulses that have little apparent bearing on issues outside of the narrow self-interest of a consumer population. He cites Paul Mazer, a Wall Street banker working for Lehman Brothers in the 1930s: "We must shift America from a needs- to a desires-culture. People must be trained to desire, to want new things, even before the old have been entirely consumed. [...] Man's desires must overshadow his needs."

In Episode 4 the main subjects are Philip Gould and Matthew Freud, the great grandson of Sigmund, a PR consultant. They were part of the efforts during the nineties to bring the Democrats in the US and New Labour in the United Kingdom back into power. Adam Curtis explores the psychological methods they now massively introduced into politics. He also argues that the eventual outcome strongly resembles Edward Bernays vision for the "Democracity" during the 1939 New York World's Fair.

According to BBC publicity:

To many in both politics and business, the triumph of the self is the ultimate expression of democracy, where power has finally moved to the people. Certainly the people may feel they are in charge, but are they really? The Century of the Self tells the untold and sometimes controversial story of the growth of the mass-consumer society in Britain and the United States. How was the all-consuming self created, by whom, and in whose interests?

Nominated for:

1. Happiness Machines

2. The Engineering of Consent

3. There is a Policeman Inside All Our Heads: He Must Be Destroyed

4. Eight People Sipping Wine in Kettering

| The Mayfair Set | |

|---|---|

Title screen of The Mayfair Set |

|

| Approx. run time | 180 min (in four parts) |

| Genre | Documentary series |

| Written by | Adam Curtis |

| Directed by | Adam Curtis |

| Produced by | Adam Curtis |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Original channel | BBC Two |

| No. of episodes | 4 |

| Followed by | The Century of the Self |

The Mayfair Set is a series of programmes produced by Adam Curtis for the BBC, first broadcast in the summer of 1999.

The programme looked at how buccaneer capitalists of hot money were allowed to shape the climate of the Thatcher years, focusing on the rise of Colonel David Stirling, Jim Slater, James Goldsmith, and Tiny Rowland, all members of The Clermont club in the 1960s. It received the BAFTA Award for Best Factual Series or Strand in 2000. [1]

Contents[hide] |

The opening episode, Who Pays Wins, focuses on Colonel David Stirling.

The rise of Jim Slater who became famous for writing an investment column in The Sunday Telegraph under the nom de plume of The Capitalist.

This episode recounts the story of how James Goldsmith became one of the richest men in the world.

By the 80s, the day of the buccaneering

tycoons was over. Tiny Rowland, James Goldsmith and Mohammed Al Fayed

were the only ones who were not finished.

Adam Curtis (born 1955) is a British television documentary maker who has during the course of his television career worked as a writer, producer, director and narrator. He currently works for BBC Current Affairs. His programmes express a clear (and sometimes controversial) opinion about their subject, and he narrates the programmes himself.

After attending Sevenoaks School (a member of the 'art room' that produced musicians, Tom Greenhalgh, Kevin Lycett and Mark White of The Mekons along with Andy Gill and Jon King of the Gang of Four) Curtis studied for a BA in Human Sciences (which included introductory courses in genetics, psychology, politics, geography and elementary statistics) at the University of Oxford. Curtis taught politics there, but left for a career in television. He obtained a post on That's Life!, where he learned to find humour in serious subjects.

Curtis's intensive use of archive footage is a distinctive touch of his. An Observer profile said:

The Observer adds "if there has been a theme in Curtis's work since, it has been to look at how different elites have tried to impose an ideology on their times, and the tragi-comic consequences of those attempts."

Curtis received the Golden Gate Persistence of Vision Award at the San Francisco International Film Festival in 2005.[1] In 2006 he was given the Alan Clarke Award for Outstanding Contribution to Television at the British Academy Television Awards.

Curtis was reported to be on the editorial 'steering committee' of the weekly email gossip newsletter Popbitch,[2] but the editor of the newsletter clarified that in fact he was simply a "friend" of the magazine.[3].

The Living Dead (subtitled Three Films About the Power of the Past) was the second major documentary series made by British film-maker Adam Curtis. This series investigated the way that history and memory (both national and individual) have been used by politicians and others. In three parts, it was transmitted on BBC Two in the spring of 1995.

Contents[hide] |

This episode examined how the various national memories of the Second World War were effectively rewritten and manipulated in the Cold War period.

For Germany, this began at the Nuremberg Trials, where attempts were made to prevent the Nazis in the dock—principally Hermann Göring—from offering any rational argument for what they had done. Subsequently, however, bringing lower-ranking Nazis to justice was effectively forgotten about in the interests of maintaining West Germany as an ally in the Cold War.

For the Allied countries, faced with a new enemy in the Soviet Union, there was a need to portray WW2 as a crusade of pure good against pure evil, even if this meant denying the memories of the Allied soldiers who had actually done the fighting, and knew it to have been far more complex. A number of American veterans told how years later they found themselves plagued with the previously-suppressed memories of the brutal things they had seen and done. The title comes from a veteran's description of what the uncertainty of survival in combat is like.

In this episode, the history of brainwashing and mind control was examined. The angle pursued by Curtis was the way in which psychiatry pursued tabula rasa theories of the mind, initially in order to set people free from traumatic memories and then later as a potential instrument of social control. The work of Ewen Cameron was surveyed, with particular reference to Cold War theories of communist brainwashing and the search for hypnoprogammed assassins.

The programme's thesis was that the search for control over the past via medical intervention had had to be abandoned and that in modern times control over the past is more effectively exercised by the manipulation of history.

Some film from this episode, an interview with one of Cameron's victims, was later re-used by Curtis in The Century of the Self series.

The title of this episode comes from a paranoid schizophrenic seen in archive film in the programme, who believed her neighbours were using her as a source of amusement by denying her any privacy, like a pet goldfish.

In this episode, the Imperial aspirations of Margaret Thatcher were examined. The way in which Mrs Thatcher used public relations in an attempt to emulate Winston Churchill in harking back to Britain's "glorious past" to fulfil a political or national end.

The title is a reference to the attic flat at the top of 10 Downing Street, which was created during Thatcher's period refurbishment of the house, which did away with the Prime Minister's previous living quarters on lower floors. Scenes from The Innocents (1961), a film adaptation of Henry James's novella The Turn of the Screw, are intercut with scenes from Thatcher's reign.

|

|||||

| Pandora's Box | |

|---|---|

The Pandora's Box titles |

|

| Approx. run time | 276 min |

| Genre | Documentary series |

| Written by | Adam Curtis |

| Directed by | Adam Curtis |

| Produced by | Adam Curtis |

| Starring | Adam Curtis (narrator) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Original channel | BBC |

| Release date | 1992 |

| No. of episodes | 6 |

Pandora's Box, subtitled A fable from the age of science, is a six part 1992 BBC documentary television series written and produced by Adam Curtis, which examines the consequences of political and technocratic rationalism.

The episodes deal, in order, with communism in The Soviet Union, systems analysis and game theory during the Cold War, economy in the United Kingdom during the 1970s, the insecticide DDT, Kwame Nkrumah's leadership in Ghana during the 1950s and 1960s and the history of nuclear power.

Curtis' later series The Century of the Self and The Trap had similar themes. The title sequence made extensive use of clips from the short film Design for Dreaming, as well as other similar archive footage.

Contents[hide] |

This part chronicles how the Bolshevik revolutionaries who came into power in 1917 attempted to industrialize and control the Soviet Union with rational scientific methods. The Bolsheviks wanted to transform the Soviet people into scientific beings. Aleksei Gastev used social engineering, and even a social engineering machine, to teach people to behave in a rational way.

There was an ongoing power struggle between bourgeoisie engineers and Bolshevik politicians. Lenin is quoted as having said "The communists are not directing anything, they are being directed". In late 1930 Stalin had 2000 engineers arrested, and eight of the most senior were accused and convicted in the Industrial Party show trial. Engineering schools were set up to train party faithfuls in only limited engineering knowledge to not threaten Stalin's political powers.

America was seen as a model for the industrialization of the Soviet Union. The city Magnitogorsk was modelled on Gary, Indiana to be the perfectly planned industrial steel mill city. A former construction worker describes how they imagined a magnificent city with palaces, houses and parks, and how workers created a park with trees made of metal because trees wouldn't grow on the steppe.

In the late 1930s Stalin arrested and purged more engineers, this time old Bolsheviks. The beneficiaries of these purges were engineers who were faithful to Stalin, and were now put in charge throughout the Soviet industry, among them were Leonid Brezhnev, Alexey Kosygin and Nikita Khrushchev. They had only narrow specialist training, and were completely unquestioning of Stalin's political aims. They set out to plan the Soviet Union as though it were a piece of engineering, with technical solutions to everything.

Gosplan, was the central organization where engineers worked with planned indicators, rational predictions of what they knew society needed. Vitalii Semyonovich Lelchuk, from the USSR Academy of Sciences, describes how everything was planned in absurdum: "Even the KGB was told the quota of arrests to be made and the prisons to be used. The demand for coffins, novels and movies was all planned."

Planners discovered that what seemed like rational assessment could lead to odd outcomes. Trains travelled thousands of miles for no other reason than to fulfill a plan that measured success in tonnes carried per kilometer. Sofas and chandeliers were made larger and larger because the plan measured material used.

Stalins successor, Nikita Khrushchev, tried to reform the plan and among other things he insisted that planners must take the price of things into account. The head of the USSR State Committee for Organization and Methodology of Price Creation is shown with a tall stack of price logbooks declaring that "This shows quite clearly that the system is rational".

Academician Victor Glushkov saw cybernetics as the solution to the issues with the complexity of the planning.

In the mid 60s Leonid Brezhnev and Alexey Kosygin took over from Khrushchev. They tried to use computerized economic planning to vitalize the failing economy. A group of three economists tell of how they assess demand using a nation-wide network of consumer correspondents, consumer panels and surveys, data which is then processed by computers. One of the ecominist explains: "The problem is industry responds very slowly to our scientific forecasts. For instance, we decided people wanted platform shoes. By the time the industry got around to increasing production they were out of fashion. Nowadays the Soviet consumer knows that if there is enough of a particular item in the shops it's a sure sign it's out of fashion."

In the late 1960s there were years of economic stagnation, and in 1978 stagnation turned into economic crisis. By the mid-1970s the Soviet leadership gave up attempts to reform the plan and the industry degenerated into pointless, elaborate ritual. Quote the narrator: "What had begun as a grand moral attempt to build a rational society ended by creating a bizarre, bewildering existence for millions of Soviet people".

This episode outlines how the US government attempted to use systems analysis and game theory to develop strategies to control the nuclear threat and nuclear arms race during the Cold War.

The focus is on the men of the on whom Dr Strangelove was allegedly based: Herman Kahn, Albert Wohlstetter and John von Neumann. These were people who believed that the world could be controlled by the scientific manipulation of fear - mathematical analysts employed by the American RAND Corporation. In the end, their visions were the stuff of science fiction fantasy.

Features several interview segments with Sam Cohen outlining his experiences at RAND. He is the inventor of the neutron bomb and was with RAND 1947-1975.

Also features George Ball, the Under-Secretary of State in the Kennedy administration 1961-1966, and William Gorham[1], RAND Corporation Asst. Sec. Dept. Health, Education & Welfare 1956-68.

Also features an interview with science fiction author Larry Niven, who was instrumental in the creating of the Star Wars policies of Ronald Reagan.

Also features Robert McNamara, Thomas Schelling, Edward Teller and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Similar material is also covered in the "Fuck You Buddy" part of Curtis' later series, The Trap, but To The Brink of Eternity has the focus entirely on the nuclear and military aspects of Cold War strategy. John Nash is not mentioned and the psychological and economical aspects of game theory are not included.

A programme on post-war economic management in the United Kingdom, and attempts to prevent relative economic decline and the perception of the 1960s Wilson governments that devaluation would jeopardize against national self-esteem.

By the mid 1970s, stagflation emerged to confound the Keynesian theories used by policy makers. Meanwhile, a group of economists had managed to convince Margaret Thatcher, Keith Joseph and other British politicians that they had foolproof technical means to make Britain 'great' again. The saga of how their experiments led the country deeper into economic decline, and asks - is their game finally up?

This part focuses on attitudes to nature and tells the story of the insecticide DDT, which was first seen as a savior to humankind in the 1940s, only to be claimed as a part of the destruction of the entire ecosystem in the late 60s. It also outlines how the sciences of entomology and ecology were transformed by political and economic pressures.

The episode appears to be named after the 1959 film Goodbye, Mrs. Ant.[2] Clips from the 1958 horror movie Earth vs. the Spider and the 1941 grasshopper cartoon Hoppity Goes to Town are also featured.

Insects were a huge problem in the United States and farmers saw whole crops destroyed by pests. Emerging in the 1940s DDT and other insecticides seemed to be the solution. As more insecticides were invented, the science of entomology changed focus from insect classification, to primarily testing new insecticides and exterminating insects rather than cataloging them. But the insecticides had side effects. As early as 1946-48 entomologists began to notice that other species of wildlife, particularly birds, were being harmed by the insecticides.

Chemical companies portrayed the battle against insects as a struggle for existence and their promotional films from the 1950s invoke Charles Darwin. Darwin biographer James Moore notes how the battlefield and life and death aspects of Darwin's theories were emphasized to suit the Cold War years. Scientists believed that they were seizing power from evolution and redirecting it by controlling the environment.

In 1962 biologist Rachel Carson released the book Silent Spring, which was the first serious attack on pesticides and outlined their harmful side effects. It caused a public outcry but had no immediate effect on the use of pesticides. Entomologist Gordon Edwards retells how he made speeches critical of Carson's book. He eats some DDT on camera to show how he'd demonstrate its safety during these talks.

The spraying of DDT in the growing suburbs brought the side effects to the attention of the wealthy and articulate middle classes. Victor Yannacone, a suburbanite and lawyer, helped found the Environmental Defense Fund with the aim to legally challenge the use of pesticides. They argued that the chemicals were becoming more poisonous as they spread, as evidenced by the disappearance of the Peregrine Falcon.

In 1968 they got a hearing on DDT in Madison, Wisconsin. It became headline news, with both sides claiming that everything America stood for was at stake. Biologist Thomas Jukes is shown singing a pro-DDT parody on America the Beautiful he sent to Time magazine at the time of the trial.[3] Hugh Iltis describes how in 1969 a scientist testified at the hearing about how DDT appears in breast milk and accumulate in the fat tissue of babies. This got massive media attention.

Where once chemicals were seen as good, now they were bad. In the late 60s ecology was a marginal science. But Yannacone used ecology as a scientific basis to challenge the DDT defenders' idea of evolution. Similar to how the science of entomology had been changed in the 1950s, ecology was transformed by the social and political pressures of the early 70s. Ecologists became the guardians of the human relationship to nature.

James Moore describes how people try to get Darwin on the side of their view of nature. In The Origin of Species nature is seen as being at war, but also likened to a web of complex relations. Here Darwin gave people a basis for urging us not to take control of nature but cooperate with it. In popular imagination a scientific theory has a single fixed meaning, but in reality it becomes cultural property and is usable by different interested parties.

Twenty years later the story of DDT continues with a press conference announcing the stop of construction in a skyscraper due to a nesting Peregrine Falcon. Ornitologist David Berger criticizes the event for fostering the myth of the sensitivity of nature.

Joan Halifax[4] talks about ecology as a gift to human beings and all species, a moral lesson that gave rise to not utopia, but ecotopia.

Politics Professor Langdon Winner theorizes that social ideals are being read back to us as if they were lessons derived from science itself. The scientific notions of the 1950s, the ideas of endless possibilities for exploitations of nature, are now seen as ill-conceived. And the ideas of ecology today may in 30 or 40 years seem similarly ill-conceived.

The episode ends with a quote from Darwin about seeking divine providence in nature: "I feel most deeply that the whole subject is too profound for the human intellect. A dog might as well speculate on the mind of Newton. Let each man hope and believe what he can."

A look at how Kwame Nkrumah, the leader of the Gold Coast (which became Ghana on independence) from 1952 to 1966, set Africa ablaze with his vision of a new industrial and scientific age. At the heart of his dream was to be the huge Volta dam, generating enough power to transform West Africa into an industrialized utopia. A scheme was drawn up together with Kaiser Aluminum, but as his grand experiment took shape, it brought with it dangerous forces Nkrumah couldn't control, and he slowly watched his metropolis of science sink into corruption and debt.

An insight into the history of nuclear power. In the 1950s scientists and politicians thought they could create a different world with a limitless source of nuclear energy. But things began to go wrong. Scientists in America and the Soviet Union were duped into building dozens of potentially dangerous plants. Then came the disasters of Three Mile Island and Chernobyl which changed views on the safety of this new technology. The episode goes into some detail over attempts to find solutions for the China Syndrome hypothesis.

This episode was named after a 1953 General Electric propaganda film explaining nuclear power and features artfully chosen footage from this film.[5]

The series was awarded a BAFTA in the category of "Best Factual Series" in 1993.[6]