Al Qaeda’s Master Spy could

be the key to them both

In its firestorm of coverage, the

mainstream media has

overlooked a potential link between the two biggest domestic terrorism

stories of the day: the shootings at Ford Hood and the decision by the

Justice Dept. to try accused 9/11 “mastermind” Khalid Shaikh Mohammed

in New York City.

Five time

Emmy-winning former ABC News

correspondent and HarperCollins author Peter Lance shines a light on

the man who may well be the greatest enigma in the “war on terror.”

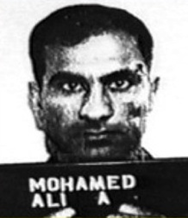

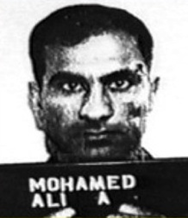

His

name is Ali Abdel Saoud Mohamed, aka Ali Amirki or “Ali the American,”

the ex-Egyptian Army officer who penetrated the CIA (briefly) in 1984,

the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg from 1987 to

1989 and the FBI where he served as an informant from the early 1990’s,

interacting with top federal prosecutors and Special Agents as he

trained the cell responsible for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing

and “Day of Terror” plots. Earlier he moved Osama bin Laden’s entourage

from Afghanistan to Khartoum, set up the al Qaeda training camps in the

Sudan, trained the Saudi billionaire’s own personal bodyguard and later

served as the principal plotter in al Qaeda’s five year mission to blow

up the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

His

name is Ali Abdel Saoud Mohamed, aka Ali Amirki or “Ali the American,”

the ex-Egyptian Army officer who penetrated the CIA (briefly) in 1984,

the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg from 1987 to

1989 and the FBI where he served as an informant from the early 1990’s,

interacting with top federal prosecutors and Special Agents as he

trained the cell responsible for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing

and “Day of Terror” plots. Earlier he moved Osama bin Laden’s entourage

from Afghanistan to Khartoum, set up the al Qaeda training camps in the

Sudan, trained the Saudi billionaire’s own personal bodyguard and later

served as the principal plotter in al Qaeda’s five year mission to blow

up the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

Ali Mohamed was the ticking time bomb at

Fort Bragg who should have

redefined the Army’s rules for uncovering traitorous Islamic radicals

in the ranks 20 years before Maj. Nidal Malik Hassan went on his

alleged rampage at Fort Hood.

But more importantly, for all the critics

who think trying KSM in

the Southern District of New York is a bad idea, Ali Mohamed could

represent the Feds’ best witness at trial; insuring once and for all

that Khalid Shaikh will finally be brought to justice.

The spy who hid in plain site

In the years leading up to the 9/11

attacks, no single agent of al

Qaeda was more successful in compromising the U.S. intelligence

community than Ali Mohamed. A member of the radical Egyptian Army unit

that murdered President Anwar Sadat in 1981, Mohammed escaped

prosecution, but he was later purged from the Egyptian military due to

his radical Islamic views.

In 1983 he caught the attention of Dr.

Ayman al-Zawahiri, five years

before the doctor with the spectacles and go-tee joined bin Laden to

form al Qaeda. Al Zawahiri saw Ali as the espionage agent he needed to

penetrate the U.S.

After the 1983 bombings of the U.S.

embassy and the Marine barracks

in Beirut, the CIA was hungry to recruit assets who understood the

radical Islamic mindset. So with very little vetting, the Agency sent

Ali to Hamburg where he went into a Hezbollah mosque only to blow his

cover and get his name on a Watch List.

Undaunted, Mohamed got onto a TWA flight

from Athens to JFK in 1985.

On the brief trip across the Atlantic, he managed to seduce an older

American woman named Linda Sanchez who was returning from vacation in

Greece. They were married six weeks later at a drive-through

wedding

chapel in Reno. After that, Ali moved into Linda’s home in Santa Clara,

California and set up an al Qaeda “switchboard” and sleeper cell with

an ex-Egyptian medical student named Khalid Dahab.

In 1986 he drove to Oakland and enlisted

in the U.S. Army, careful

to stay under the radar and avoid the scrutiny of Officer Candidate

School. Astonishingly, though still a resident alien, he was posted to

Fort Bragg where he managed to work his way up to the rank of E5

(sergeant) and, without any security clearance, get posted to the

highly secure JFK SWC where elite Green Beret and Delta Force officers

train.

A chilling precursor

So far, in its official reaction to the

Fort Hood massacre the U.S.

Army has been taking a page from the Claude Raines school of crisis

management; imitating the reaction of the duplicitous Capt. Renault in

the film Casablanca who professed, “shock, shock” that there

was gambling going on at Rick’s club only to be handed his winnings.

But two decades before Maj. Hasan

allegedly dropped thirteen people

in cold blood, key officials at Bragg were aware of Ali Mohamed’s

openly jihadist views. They even used him in a training video, in which

Ali declared (with chilling confidence) that it was the duty

of all Muslims to change countries with secular governments into

Islamic regimes.

“It’s an obligation,” said Ali on the

training tape, “it’s not a choice.”

And how much was known at Bragg among the officer elite of Ali’s

subversive agenda? Ask his own commanding officer, Col. Robert Anderson:

“I think you or I would have a better

chance of winning the

Powerball lottery, than an Egyptian major in the unit that assassinated

Sadat would have getting a visa, getting to California, getting into

the Army and getting assigned to a Special Forces unit. That just

doesn’t happen.”

But it did and Ali was so audacious at

Bragg that he announced to

Anderson that he was going to use his leave to visit Afghanistan and

hunt Soviets. It was an act that could have had global implications

akin to the Soviet shoot down of Francis Gary Powers’ U-2 flight, if

Mohamed had been captured or killed in the midst of the covert U.S. war

to help the Mujahideen.

In an interview for my HarperCollins

biography of Mohamed, Triple

Cross, Anderson

said that he tried to get Ali court martialed after he returned from

Kabul and brazenly dropped two belts from Soviet Spetsnaz commandos on

his desk. Bragging that he’d killed them, Ali wasn’t worried in the

slightest that he’d be reprimanded and Anderson said he was told by a

JAG officer that there was insufficient evidence “to convict anyone of

anything.”

Does this resonate with the kind of

audacious behavior Maj. Hasan

exhibited at Walter Reed Army Hospital only to be given a pass? As the

French say, “plus c’est change, plus c’est la meme chose.”

Al Qaeda’s secret spy in New

York

But the Afghan theater of ops wasn’t

where Ali Mohamed did his most

damage. On weekends, in 1989 he began commuting up to New York from

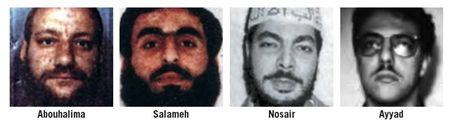

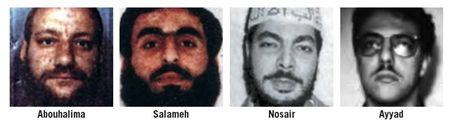

Fort Bragg where he trained Mahmoud Abouhalima, a six foot two-inch red

headed Egyptian cab driver, Mohammed Salameh, a Palestinian illegal

alien, and Nidal Ayad, a Kuwait émigré and Rutgers grad –

all later

convicted by Southern District prosecutors in the 1993 World Trade

Center bombing.

Working out of what the Feds called “the

Jersey jihad office,” the

Kennedy Boulevard based Al-Salaam mosque in Jersey City, Ali even

played his Fort Bragg training video for the “brothers” as he schooled

them in and weapons training and other covert operations.

Should

the Army have known about Ali’s clandestine trips back then? Maybe not

initially, but the alarm bells should have gone off at the JFK SWC in

November, 1990 when El Sayyid Nosair, another Ali trainee, gunned down

Rabbi Meier Kahane, founder of The Jewish Defense League as he gave a

speech at the Marriot Hotel on Lexington Avenue.

Should

the Army have known about Ali’s clandestine trips back then? Maybe not

initially, but the alarm bells should have gone off at the JFK SWC in

November, 1990 when El Sayyid Nosair, another Ali trainee, gunned down

Rabbi Meier Kahane, founder of The Jewish Defense League as he gave a

speech at the Marriot Hotel on Lexington Avenue.

That night as multiple law enforcement

units descended on Nosair’s

house in New Jersey they found a treasure trove of intelligence

suggesting that Ali Mohamed (who stayed with Nosair on his New York

visits) had betrayed not only the U.S. Army, but his adopted country.

They filled forty-seven boxes with

evidence seized, including Green

Beret manuals marked “Top Secret for Training” and communiqués

classified as Secret from the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Another memo, entitled “Location of

Selected Units on 05 December

1988,” listed the precise positions of Special Operations Forces (SOF)

worldwide—including the army’s Green Berets and Navy SEAL teams—along

with details of their missions. That single communiqué could

have

easily gotten Mohamed indicted on charges of espionage and treason,

defying the legal judgment of the JAG officer at Bragg who had spurned

Lt. Col. Anderson’s request for a court martial.

A warning of the 1993 World

Trade Center bombing

The cache also contained hints of al

Qaeda’s most famous New York

target: the World Trade Center. One passage inside Nosair’s notebook

called for the “destruction of the enemies of Allah…by… exploding…their

civilized pillars…and high world buildings.”

Considering the “stove piping” that

existed back then, you might ask

how would the FBI have known about Ali’s presence at Fort Bragg or his

links to El Sayyid Nosair?

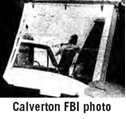

Fair question, until you realize that 16

months before the

Kahane assassination, the FBI Special Operations Group followed Nosair

and a group of other “ME’s” (middle eastern men) from a Brooklyn mosque

to the Calverton shooting range on Long Island.

Over four weekends in July, the Bureau

agents took dozens of

surveillance photos of Nosair, Abouhalima, Salameh, Nosair and Ayad

(all trained by Ali Mohamed) firing handguns, AK-47’s and other

semi-automatic weapons. They even had shots of the chrome-plated .357

Magnum, Nosair would use to rub out the rabbi.

The “lone gunman”

Even more shocking, when you ponder why

the dots weren’t connected,

was the presence of Abouhalima and Salameh, Nosair’s intended getaway

driver’s, at his New Jersey home the night of the assassination.

They were taken into custody; only to be

released by the NYPD the

next day. Later, despite the involvement of three co-conspirators,

Chief of Detectives Joe Borelli labeled the assassination a “lone

gunman shooting.”

Nosair, a Prozac popping janitor who

worked in the basement of

Manhattan’s civil court was tried locally by the Manhattan D.A. and to

the surprise of Bill Greenbaum, the ADA who prosecuted the case, the

Army kept their distance.

“We had people from Fort Bragg who came

up,” he told me. “But then they went home and we never heard a word.”

Nosair lawyered up with William Kuntsler

who succeeded in getting

him convicted on mere weapons charges vs. the actual Kahane murder.

Years after the 9/11 attacks Eleanor Hill, chief investigator for the

House-Senate Joint Inquiry, revealed that Osama bin Laden himself

helped pay for Nosair’s defense.

The first U.S. blood spilled

by al Qaeda

The legal fee from the Saudi billionaire

suggested that the rabbi’s

death at the hands of an Ali Mohamed-trainee was the first in a series

of al Qaeda missions directed against U.S. citizens; the next being the

murder of six people in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, the 1998

Embassy bombings, the loss of 17 sailors in the bombing of the U.S.

Cole in 2000 and the mass murder of 2,976 on 9/11.

Ali Mohamed was personally connected to

three of those five acts of

terror. In the Embassy plot, he actually took the surveillance pictures

that bin Laden used to pinpoint the location of the suicide truck bombs.

And what about the culpability of the two

“Bin Laden offices of

origin;” The FBI’s New York Office (NYO) and the Office of the U.S.

Attorney for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) in failing to

sniff out Mohamed as an al Qaeda spy?

In retrospect their record is shameless.

But the seeming inability

of the Southern District Feds to connect the dots continued up through

the mid 1990’s.

In prepping for the 1995 “Day of Terror”

plot, an al Qaeda scheme to

blow up the bridges and tunnels into Manhattan, assistant U.S.

attorneys Patrick Fitzgerald and Andrew C. McCarthy put together a list

of 172 un-indicted co-conspirators.

Ali Mohamed was on the list along with Osama bin Laden and a little

known individual named Waleed al Noor – co-owner with Egyptian Mohammed

El-Attris of a small check cashing and mailbox story in Jersey City

called Sphinx Trading.

If the Feds had any doubts about how

“mobbed up” with al Qaeda

Sphinx was, all they had to do was visit the building that housed the

“Jersey Jihad” office and the al Salaam mosque where blind Sheikh

Omar

Abdel Rahman, al Qaeda’s spiritual leader, held court. Sphinx Trading

was on the ground floor.

The 9/11 dots that never got

connected

One of the most shocking discoveries I

made in researching Triple Cross was that, six and a half

years after

McCarthy and Fitzgerald put Waleed al-Noor on that list with bin Laden

and Ali Mohamed, Khalid al-Midhar and Salim al-Hazmi, two of the muscle

hijackers who flew AA Flight #77 into the Pentagon on 9/11, got their

fake ID’s at Sphinx from Mohammed El-Attriss, al-Noor’s partner.

Meeting Mohamed face to face

In 1996, Assistant U.S. Attorney Patrick

Fitzgerald (now the top

Federal prosecutor in Chicago) was charged by DOJ brass with getting an

indictment of bin Laden. He turned to Squad I-49 in the FBI’s NYO where

he began working with Special Agents Jack Cloonan and Dan Coleman.

By the summer of 1997, suspecting that

something very bad was

developing in Africa, Fitzgerald sent Coleman to Nairobi where he

searched the home of Wadih El Hage, a bin Laden confident who was one

of the principal bombing plotters.

Coleman was shocked to discover links

between El Hage and Ali

Mohamed, who had been cooperating with the Feds since 1992. That

prompted Fitzgerald himself to fly across country to Sacramento where

Ali was then living. In a face to face meeting, the federal prosecutor

naively hoped he could turn Mohamed.

But Ali was not about to betray his

“sheikh,” Osama. He actually

admitted to Fitzgerald that he “loved” bin Laden and “believe[d] in

him.” Then, he uttered words that amounted to treason; boasting that he

didn’t need a fatwa to make war on the U.S., since America

was “the enemy.” There was no way he was going to betray the jihad to

these hapless Feds. Finally, he got up and left.

Moments later, Fitzgerald turned to

Cloonan and said, “That is the

most dangerous man I have ever met. We cannot let this man out on the

street.” But that’s just what he did; allowing Ali to remain free for

another 10 months; waiting to arrest him until a month after

the bombs went off in Africa killing 224 and injuring thousands. It was

a plot that Ali had been perfecting since 1993.

Cutting a deal with the

devil’s “aide”

Back at Fort Bragg, Col. Anderson, Ali’s

C.O. had described him to

me as a “fanatic.” He wasn’t the devil, the Colonel said, “ he was more

like the aide to the devil. He had an air about him; a stare, a very

coldness that was pathological.”

Does that not echo the growing testimony

we’ve heard from Army colleagues who interacted for years with Maj.

Nidal Malik Hasan?

It took Fitzgerald more than a year to

get any real cooperation out

of Mohamed. It wasn’t until the year 2000 that Ali finally pled guilty

to the Embassy bombings in return for being spared the death penalty.

The problem was, as the months counted

down to the 9/11 attacks, why

didn’t he give up the “planes as missiles plot?” From what Cloonan told

me, Mohamed knew every detail. How could a top Fed like Pat Fitzgerald

cut a deal with al Qaeda’s chief spy and not squeeze the truth out of

him about bin Laden’s ultimate goal?

In PART TWO we’ll look at how

much Ali may have known

about the 9/11 plot and why, if the Feds were smart, he could become

the secret weapon against KSM.

His

name is Ali Abdel Saoud Mohamed, aka Ali Amirki or “Ali the American,”

the ex-Egyptian Army officer who penetrated the CIA (briefly) in 1984,

the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg from 1987 to

1989 and the FBI where he served as an informant from the early 1990’s,

interacting with top federal prosecutors and Special Agents as he

trained the cell responsible for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing

and “Day of Terror” plots. Earlier he moved Osama bin Laden’s entourage

from Afghanistan to Khartoum, set up the al Qaeda training camps in the

Sudan, trained the Saudi billionaire’s own personal bodyguard and later

served as the principal plotter in al Qaeda’s five year mission to blow

up the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

His

name is Ali Abdel Saoud Mohamed, aka Ali Amirki or “Ali the American,”

the ex-Egyptian Army officer who penetrated the CIA (briefly) in 1984,

the John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg from 1987 to

1989 and the FBI where he served as an informant from the early 1990’s,

interacting with top federal prosecutors and Special Agents as he

trained the cell responsible for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing

and “Day of Terror” plots. Earlier he moved Osama bin Laden’s entourage

from Afghanistan to Khartoum, set up the al Qaeda training camps in the

Sudan, trained the Saudi billionaire’s own personal bodyguard and later

served as the principal plotter in al Qaeda’s five year mission to blow

up the U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Should

the Army have known about Ali’s clandestine trips back then? Maybe not

initially, but the alarm bells should have gone off at the JFK SWC in

November, 1990 when El Sayyid Nosair, another Ali trainee, gunned down

Rabbi Meier Kahane, founder of The Jewish Defense League as he gave a

speech at the Marriot Hotel on Lexington Avenue.

Should

the Army have known about Ali’s clandestine trips back then? Maybe not

initially, but the alarm bells should have gone off at the JFK SWC in

November, 1990 when El Sayyid Nosair, another Ali trainee, gunned down

Rabbi Meier Kahane, founder of The Jewish Defense League as he gave a

speech at the Marriot Hotel on Lexington Avenue.