• Why Study the Bohemian Grove? Social Cohesion And Policy Cohesion

• The History of the Bohemian Club and Its Grove Encampment

• The Cremation of Care Ceremony

• The Camps at the Bohemian Grove

• The Sociology of Bohemia: The Corporate and Social Connections of Members and Guests

|

The Bohemian Grove is a 2,700-acre virgin redwood grove in Northern California, 75 miles north of San Francisco (map), where the rich, the powerful, and their entourage visit with each other during the last two weeks of July while camping out in cabins and tents.

It's an Elks Club for the rich; a fraternity party in the woods; a boy scout camp for old guys, complete with an initiation ceremony and a totem animal, the owl. It's owned by the Bohemian Club, which was founded in San Francisco in 1872. The Bohemians started going on their little retreat shortly after the club was founded; it became big-time by the 1880s, and it continues today.

However, it is not a place of power. It's a place where the powerful relax, enjoy each other's company, and get to know some of the artists, entertainers, and professors who are included to give the occasion a thin veneer of cultural and intellectual pretension. Despite the suspicions of many on the Right, and a few on the Left, it is not a secret meeting place to plot, plan, or conspire. The most important decisions typically happen just where we might expect: in the boardrooms of corporations and foundations, at the White House, and in the backrooms of Congress. Yes, as I show later, some wanna-be and has-been Republican politicians sometimes visit the Bohemian Grove, including future and former presidents of the United States, but they are there to demonstrate what wonderful human beings they are, to cultivate potential financial backers, or to brag about their past exploits.

Readers who suspect that every gathering of the rich and the powerful has some deeper purpose may doubt this claim, at least until they see my evidence. For those who still might question my conclusions after reading this article, I recommend reading an excellent first-hand account of the Bohemian Grove by a journalist from Spy magazine who snuck into the encampment in 1989; the author had every incentive to tell it exactly as he saw it. More recently, a reporter from Vanity Fair snuck into the Grove during the 2008 encampment to investigate logging activity as well as the usual goings-on, and his experiences are summarized in a May 2009 article entitled "Bohemian Tragedy."

In fact, every person who has written seriously on the Bohemian Grove agrees: even though they provide evidence that there is a socially cohesive upper class in the United States, the activities at the Grove are harmless. The Grove encampment is a bunch of guys kidding around, drinking with their buddies, and trying to relive their youth, and often acting very silly. These activities do contribute to social cohesion as an unintended consequence -- which is why I decided to study the Bohemians in the first place -- but the Grove is merely a playground for the powerful and their entertainers that gives us a window into a lifestyle that is far removed from that of average Americans.

If this is a web site about power, politics, and social change, why bother with the Bohemian Grove if it is not a place of power?

That's a fair question, and an important one in terms of differentiating rival theories of power in the United States. The answer goes back to the kind of criticisms that used to be made of a class-domination theory by the most important group of theorists in the social sciences during the 20th century, the pluralists. Pluralists deride the idea that there could be class domination in the United States, and one of the reasons they do is that the upper class of rich people is allegedly too fragmented to be able to organize for power. Heck fire, them rich people don't even know each other, most of 'em. All those wealthy capitalists that theorists like me talk about are just a list of names, not a for-real social class.

So I was looking for an opportunity to show pluralists differently when I unexpectedly noticed that a wealthy liberal lawyer I was about to interview in late 1970 about campaign finance -- you know, the kind of stuff I should be studying -- had the membership lists for the Bohemian Club and the even more exclusive Pacific Union Club on a shelf in his waiting room. We hit it off well during the interview, and he clearly liked to stir things up, so I asked him if I could photocopy the lists. He said "sure." and I was off and running. Those two membership lists gave me the starting point for a study that would allow me to trace the social backgrounds and corporate connections of men who slept together in cabins and tents in the California redwoods, so I figured you couldn't get more "socially cohesive" than that.

Moreover, there is a literature in social psychology, called small-group research, or small-group dynamics, which shows that people who meet in relaxed settings, and see their group as exclusive, become even tighter with each other than people in ordinary groups. Even better, people in exclusive groups are more likely to listen to each other and come to a compromise if they have the task of figuring out what to do about some policy issue.

In short, a study of the Bohemian Grove could show that social cohesion is an aid to the formation of policy consensus. I took to saying that from a social-psychological point of view, the upper class is made up of constantly shifting face-to-face small groups -- a board of directors meeting at the corporation in the morning, a meeting of a policy discussion group in the afternoon, a drink with some buddies at an exclusive club in the evening. And best of all, of course, many of them camped out together at the Bohemian Grove one year or another.

Although my study was well received in many circles, it did not convince anyone, and it got me some new criticisms besides. The pluralists promptly distorted what I argued by saying I was a conspiratorial thinker who believes that policy is made in secret at the Bohemian Grove. At the same time, the usual pluralist claim that the upper class was not "cohesive" slowly faded away in favor of more emphasis on standard arguments that are dealt with elsewhere on this web site. (For my views on conspiratorial thinking, click here.)

Some of the fancier theorists of that by-gone day panned the study too. They thought it was trivial and irrelevant. Why worry about social cohesion as a factor in policy cohesion when the structural imperatives of capitalism make capitalists well aware of their interests and all too ready to agree on government policies that will further those interests? They didn't buy my belief that it was necessary to take the issues concerning social cohesion and social psychology seriously. Whereas I thought that Texas oilmen and Wall Street bankers might well need a little fraternizing to come to trust each other, my critics on the left said the differences from industry to industry and region to region were trivial.

Things didn't get any better when a few left-wing activists grabbed onto my book and said that there were in fact political conspiracies hatched at the Bohemian Grove. They said that the atomic bomb was planned at the Grove, for example, a claim that misses all the key points about what I said in my book on this issue. (A member of the Grove asked the club president if he could use the area during an off-season month to meet with other A-bomb planners; no other Bohemians were present, or knew about the secret meeting, which could have been held anywhere.)

A few years later, some extreme right-wingers got hold of my book and concluded that the "Cremation of Care" ceremony, a harmless put-on that starts the encampment, in fact promotes devil worship and homosexuality. One rightist even suggests there is child sacrifice at the Bohemian Grove. An alarmist video and a web site make these incredible -- and nonsensical -- claims.

So now I am writing about the Bohemian Grove for another reason as well as the original one: to set the record straight. Contrary to what some leftists think, any political discussions that happen there could have been held at any one of several other venues where such discussions usually occur -- for example, restaurants, downtown men's clubs, golf courses, policy-discussion groups, and board of director meetings. Contrary to the rightists, the activities are harmless.

Well, they of course talk politics now and then, and hear speeches by would-be and former political leaders, but that's not what the conspiratorial thinkers on either side of the political spectrum are talking about. (You'll learn more about the political guests in the section on Lakeside Talks.)

I used four very different methods to put together the story of the Bohemian Grove: membership network analysis, archival searches in historical libraries, interviews with informants, and participant observation at the downtown clubhouse and the Bohemian Grove itself.

The membership lists for the Bohemian Club and the Pacific Union Club were my starting point. If the Bohemians didn't overlap with the Pacific Union Club, a for-sure upper-class club, the study might have stopped right there. But they did overlap. Moreover, members of both clubs were often in the San Francisco Social Register, an upper-crust telephone book, called a "blue book" in the old days. I was confident that the Bohemian Club was an upper-class venue, but I soon learned that many members were not members of the upper class -- for reasons that help to make the club unique.

The next step was to study the social club and policy connections of all the Bohemians. This part of the study showed that many Bohemians were corporate chieftains, members of policy-planning groups, trustees of think tanks and opinion-shaping groups, and members of social clubs all over the country. We constructed a large matrix based on the overlapping members in 30 of these types of organizations. When we studied it with a fancy program for "network analysis," the Bohemian Club was No. 11 in "centrality"; see the table below. (For a very interesting and colorful account of The Links Club of New York, the most central club and third-most central organization overall, check out this portrait by an avid middle-class golfer who convinced a "certified WASP" member to let him visit.

Centrality Rankings of 30 Organizations

| Name of Organization | Type of Organization | Centrality Score (0-1) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Business Council | Policy-planning group | .95 |

| 2. Committee for Economic Development | Policy-planning group | .91 |

| 3. Links Club (NY) | Social club | .80 |

| 4. Conference Board | Policy-planning group | .77 |

| 5. Advertising Council | Opinion-shaping group | .73 |

| 6. Council on Foreign Relations | Policy-planning group | .68 |

| 7. Pacific Union (SF) | Social club | .67 |

| 8. Chicago Club (Chicago) | Social club | .65 |

| 9. Brookings Institution | Think Tank | .65 |

| 10. American Assembly | Policy-planning group | .65 |

| 11. Bohemian Club (SF) | Social club | .62 |

| 12. Century Association (NY) | Social club | .48 |

| 13. California Club (LA) | Social club | .46 |

| 14. Foundation For American Agriculture | Think tank | .45 |

| 15. Detroit Club (Detroit) | Social club | .44 |

| 16. National Planning Association | Policy-planning group | .36 |

| 17. Eagle Lake (Houston) | Social club | .33 |

| 18. National. Municipal League | Policy-planning | .33 |

| 19. Somerset Club (Boston.) | Social club | .32 |

| 20. Rancheros Vistadores (Santa Barbara) | Social club | .26 |

| 21. National Association of Manufacturers | Trade Association | .25 |

| 22. Farm Film Foundation | Opinion-shaping group | .22 |

| 23. 4-H Advisory Committee | Opinion-shaping group | .21 |

| 24. Piedmont Driving (Atlanta) | Social club | .21 |

| 25. Chamber of Commerce Farm Committee | Policy-discussion group | .18 |

| 26. Farm Foundation | Think tank | .13 |

| 27. National Farm-City Council | Opinion-shaping group | .11 |

| 28. Harmonie Club (NY) | Social club | .08 |

| 29. American Farm Bureau Federation | Trade association | .08 |

| 30. German Club (Richmond) | Social club | .03 |

| Source: G. William Domhoff, "Social clubs, policy-planning grups, and corporations: A network study of ruling-class cohesiveness," The Insurgent Sociologist, Vo. 5, No. 3, 1975, p. 178. | ||

As far as social structure goes, this centrality analysis was the heart of the Bohemian Grove study. But to delve into social cohesion and social psychology, it was necessary to know more about the club, such as its history and current activities, so off I went to libraries, especially stand-alone historical libraries that are full of upper-class memorabilia, not scholarly books. There I found old histories of the club, along with histories of specific camps and a text of the Cremation of Care ceremony. It was a bonanza. Among other things, I could then check the names of 19th century members against membership lists for other clubs and organizations to learn more about the social origins of the founding members. (In these libraries, I also found most of the pictures that accompany this essay.)

Informants played an important role in the study. I asked everyone I knew in and around Santa Cruz, which is only 150 miles from the Bohemian Grove, if they knew anything about it, and soon found students who knew students who had worked there, and friends who had friends who had once been performing members -- i.e., members who pay reduced dues in exchange for helping to put on all the entertainment that goes on at the Grove. Just as I was finishing my study, I learned that a person in Santa Cruz I knew well had once been a member, and he contributed greatly to the final version of the study by adding little details that would make it clear to anyone who knew anything about the Grove that I had a good informant, or was a secret member, or something. For instance, he told me of a camp, called Poison Oak, that served a lunch called Bulls' Balls Lunch, where everyone came by to eat roasted cattle testicles brought by a rancher from near Fresno, CA. Another camp had a soft porn collection.

One invaluable informant was a long-haired grad student at Berkeley who was very nervous about talking to me when I arrived at his house in Oakland about 9 a.m. one morning. We hadn't been talking long when he asked me if I would like a hit. I didn't really want one, but I felt caught -- if I said no, he might trust me even less. So I said yes and he led me to a big drawer in a closet, where he had an amazing stash, with joints of many different qualities. We each had a few hits of a Grade B joint, and then he suddenly said I could have the rest. I tried to be cool, but I was soon too far gone to know for sure what he was talking about. I excused myself every few minutes to go to the bathroom, where I'd pinch my hands and arms to try to sober up, splashed cold water on my face, slapped myself, breathed deep. I eventually comprehended most of what he had to say, and what he had to say was absolutely incredibly helpful, but my notes went up and down and all around on page after page.

It was from this informant that I learned for the first time what a big deal the Cremation of Care ceremony was in the eyes of the members. Now I knew that the script for it that I had found in the Stanford University Library was very important. He had first told me about the Cremation at the start of our chat, and I had hurried past it, thinking I would come back to it, because I wanted to get a sense of the whole encampment before we got into details. But when we went back to talk about the Cremation ceremony, he decided he didn't want to give me any details because he knew the ceremony meant so much to the members. He said he wanted to respect their pride in it. But he had told me what I needed to know -- it was a big deal.

Three friends of friends took me to lunch at the Bohemian Club downtown. None knew of my other Bohemian informants. On the second and third visits, when I was asked if I had been there before, I told a little white lie and said "no," and took two more tours of this four-story building. Each time I quickly sat down after leaving my host to write down every detail I could remember.

Then a friend of a friend took me into the Grove for what is called the "June Picnic" or "Ladies' Day." This man was an architect who could sketch anything, and he made drawings of the Cremation ceremony and the High Jinx stage setting for me. While in the Grove I saw the mighty Owl statue by the artificial lake, which is described in the section on The Cremation of Care, and everything else there was to see. I asked many questions of the students who were driving the tram buses around the Grove. One said the best way to understand the Grove was to imagine that the fraternity system at UC Berkeley had been moved into redwood camps; I used that line in my book. I also obtained several picture postcards of the encampment during this visit.

Earlier in the research process I had tried to make "official' contact with the club leaders by asking for an interview, but they hadn't even replied, perhaps hoping I would give up and go away. Eventually they must have gotten wind of my study, because one day I received a telephone call from -- for a Bohemian -- a relatively young guy, maybe in his 40s. He was the head of one committee or another, and said he'd be glad to talk to me. They were clearly worried I might spread misinformation, so figured at this point it was better to talk to me. So back I went to the downtown club for another "first time" visit. This man had two main concerns -- that I would mention that there had been no black members (he said there would be one or two soon) and that I would exaggerate the amount of prostitution around the Grove (I already knew from journalists in the area that there was not as much as storytellers claimed). What made all this amusing was, first, that he had no shame that there hadn't even been any Jewish members until a year or two before, and he readily admitted some anti-Semitic comments were made when the first Jewish candidates were proposed -- and this in the early 1970s. Second, he regaled me with tales about the amount of drinking that goes on at the Grove, which is hardly an impressive advertisement for it.

So, it was a "multi-method" study. I wouldn't have bothered to do such a study if I hadn't secured those membership lists, but it wouldn't have been as interesting if I hadn't gone to historical libraries, talked to informants, and visited the Grove itself.

The Bohemian Club was founded in the early spring of 1872 by a small group of San Francisco journalists, writers, actors, and lawyers who wanted to have a place where they could go to enjoy the arts and put together amateur artistic performances. They were young and spirited in a still-young, still-small city that was infused with a can-do spirit based on the Gold Rush and the possibilities of trade with the Orient, among many new possibilities that had opened up since California was incorporated into the United States in 1850.

Right from the start, though, the club also included those with an "appreciation" of the arts, which meant some of their businessman buddies. As one well-to-do founding member put it in his memoirs: "It was apparent that the possession of talent, without money, would not support the club." So the founders decided that the club should include men "who had money as well as brains." Thanks to this decision, he continued, "the problem of our permanent success was solved."

Thus, contrary to what is often claimed, a club of artists was not "taken over" later on by the well-to-do. The Bohemian Club was an elite social club from the start, and was so considered by the San Franciscans of the day. The club soon had several hundred members who enjoyed taking part in the many dramas, musicals, and comedies sponsored by the club.

Some of the richest men in San Francisco enjoyed membership. While not considered as high status as the Pacific Union Club, it was listed in the Elite Directory (1879), the San Francisco Blue Book (1888), Our Society Blue Book (1894-95), and other social registers of that era. By 1879 one in every seven members of the very exclusive Pacific Union Club was also a member of the Bohemian Club, with the figure climbing to one in five by 1894 and one in four by 1906. In 1907, the first year for which the California Historical Society in San Francisco has copies of the yearly San Francisco Social Register, 31% of the regular local Bohemian Club members were listed in its pages.

Right from the start, there was constant friendly argument about the differences between artists and men of commerce. For example, a few people objected to the very name of the club because "Bohemian" meant then what it means now, at least to some people, a carefree, unconventional vagabond, not quite respectable. It's an image that stretches from the centuries-old French folk belief that European gypsies were originally from the country of Bohemia. American artists searching for a lifestyle picked up the term while lounging in the Paris cafe's of the 1850s. They returned to the United States to paint a picture of Parisian Bohemianism which made the artists' colony there the envy of American artists and university students ever after.

So the new Bohemian Club was meant to be "Bohemian" in the Parisian and New York artist sense. As the leaders said in their founding statement, it was to be a club for "the promotion of social and intellectual intercourse between journalists and other writers, artists, actors and musicians, professional or amateur, and such others not included in this list as may by reason of knowledge and appreciation of polite literature and the fine arts be deemed worthy of membership."

|

| (click to enlarge) |

It didn't take the club long to start going on the little summer jaunts that eventually became the Bohemian Grove encampment. In the summer of 1873 several members took the Sausalito Ferry to the charming little Marin County town of Sausalito for an afternoon picnic, and by 1878 they had made the trip into an all-day occasion. Gradually a day turned into a weekend, and then into a trip further north to Santa Rosa County, to an area then know as Meeker's Grove, where the "Cremation of Care" was first performed in 1880. Throughout the 1880s, the members simply rented Meeker's Grove for their outings, and even went to a nearby setting in one year.

But in the 1890s, when Mr. Meeker was thinking about selling his redwood grove to the logging companies that were working nearby, the Bohemians decided the Grove was now too much part of their heritage to abandon. So they decided to buy it, at the time a mere 160 acres. Then another 120 acres was added in the next few years. When a real-estate development was started on nearby land in 1913, the club moved to stop that "threatened encroachment" by buying hundreds and hundreds more acres. Land purchases continued throughout the decades, and the Grove reached its present size of 2,700 acres in 1944. (Some controversy has arisen in recent years over the Bohemian Club's plans to log its own property, ostensibly in the name of fire prevention; see the Los Angeles Times, 8/21/06, or the San Francisco Chronicle, 7/12/07.)

In terms of present-day ceremonies and plays, everything was in place by the late 1890s. Several magazines of the era wrote about the occasion, stressing its cultural aspects. Visiting dignitaries were taken to the Grove when they came to the city. A visit by President Teddy Roosevelt and his family in 1905 was duly mentioned in a city newspaper.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

The Bohemian Club struggled mightily in the late 19th century to establish its ties with "real Bohemianism." Ambrose Bierce, later to be one of the fathers of West Coast Bohemianism, and the author of such semi-classics as The Devil's Dictionary, was a founding member, although at that time he was listed as an employee at the federal mint. So was poet Charles Warren Stoddard, who in 1876 gained great notoriety by accompanying New York's so-called "Queen of Bohemia," Ada Clare, on a sightseeing trip in Hawaii. Writers Bret Harte and Mark Twain were made honorary members. George Sterling, who had an uncle who was a prosperous real-estate man, but himself took a vow of poverty so he could be a real Bohemian in the Parisian sense, became one of the leaders of Western Bohemianism when be turned to poetry and was asked to join the Bohemian Club in 1904 -- which gave it a renewed air of authenticity. Even socialist author Jack London, who resisted the label of Bohemian for that of vagabond, was acceptable for membership at the turn of the century, although there was some concern expressed over his radical ideas and his fancy white silk shirts with long, flowing ties.

Meanwhile, the banter between artists and business leaders continued, based on the usual human tendency to romanticize "the good old days." In 1880, a mere 8 years after the club's founding, a group of painters and writers protested that "the present day is not as the past days, the salt has been washed out of the club by commercialism, the chairs are too easy and the food too dainty, and the true Bohemian spirit has departed." Around the turn of the century one early member anonymously decried this change in spirit in a little booklet on "Early Bohemia." "The entering of the money-social element has not benefited the club, as a Bohemian Club," he claimed. Now the club had "social aspirations which means death to genius and a general dead-level mediocrity."

But enough of this kind of stuff. A little history goes a long way when it comes to the Bohemian Club because it's always the same old story.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

The Bohemians have a downtown "clubhouse" that is their main base of operations. It is an imposing six-story building only a few blocks from the financial district of downtown San Francisco. It contains all the amenities of the usual upper-class club, except that it has no athletic facilities whatsoever. For more active pursuits, such as swimming, people have to become members next door at the Olympic Club or up the hill a few blocks at the Pacific Union Club.

The main floor of the clubhouse contains the traditional oversized reading room with large stuffed chairs. The reading room looks like it was developed from one of the traditional clubman cartoons in The New Yorker. It features newspapers and magazines from all over the world, little statues on pedestals and tables, high-vaulted ceilings, a plush Oriental rug, and members reading their Wall Street Journals. "It's almost like a church in its atmosphere," says one non-businessman member.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

There's also an equally large domino room on the main floor, where men can satisfy their gaming passions at little green tables seating four people. Lunchtime tournaments are held quite regularly. The pride of the main floor, however, is the "cartoon room," an extremely spacious barroom, complete with piano and small stage, and decorated with the paintings, handbills, posters, and cartoons drawn by famous club artists for jinks and testimonial dinners of the past. Dice lie conveniently on the bar itself so gentlemen can indulge their gambling urge as a means of determining who signs the check for the drinks. In the first picture at right, you can see some members having a drink there; notice the drawing of an owl on the window above the bar. The owl is the totem animal of the Bohemian Club because it is wise, nocturnal, and discreet. The second picture provides a close-up of the cartoon room in the old days.

Just off the cartoon room there is a little art gallery. The small shows in the gallery are changed frequently, and of course feature the work of associate members of the club.

A very large dining room and a library room occupy the second floor. The dining room is used for daily lunches as well as for most of the regular Thursday night club entertainments. (For generations, Thursday night was maid's night off everywhere in the United States, a small but revealing sign of the nationwide nature of the upper class.) On the same floor is a smaller dining room called the Grove Room. Its walls are completely covered with beautiful murals of the center of the Grove. The Grove Room is used for more intimate luncheons and parties.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

This next picture shows the library. The big bulky books on the front table are scrapbooks containing pictures and stories from Grove encampments.

For extremely large parties, testimonial dinners, and dances, there are a reception room and a banquet room in the basement. These rooms, along with the large art gallery on that floor, are sometimes rented by members for private parties and wedding celebrations. The subbasement of the clubhouse is a large theater (seating capacity: 611) where the biggest performances of the regular year are held. The theater also is in constant use for rehearsals for plays that will be given at the Grove, and for orchestra and band practice. Right behind the theater there is a shop for making stage sets, as well as costume rooms and makeup rooms.

The top two floors of the clubhouse contain small meeting rooms, rehearsal rooms, and several small apartments and rooms, which usually are rented to older resident members or out-of-town members temporarily located in San Francisco. There is a glass-covered sun deck on the roof.

The Bohemian Club is governed by a 15-man board of directors elected from among the regular members by a vote of regular members only. The directors, of course, do very little of the day-to-day work themselves. To carry out their wishes they have a hired manager, who in turn has a large staff of cooks, waiters, carpenters, and laborers.

Like most organizations in the United States, the club is run through a set of semiautonomous committees, and it is the job of the board of directors to appoint these committees. In this case there are such committees as a Jinks Committee to look after shows and plays, a Grove Committee to take care of the maintenance of the Grove, a House and Restaurant Committee to direct the dining facilities, an Art Committee, a Library Committee, and a Membership Committee.

Perhaps the most enjoyable service is on the Wine Committee. It meets about five times a year for "working" sessions. According to one annual report, the committee savored 35 new wines that year, accepting only 10 to a club stock that includes well over 125 different wines. The committee also makes sure that 3,500 bottles of wine are available for purchase by members and guests at the Grove encampment. The head of the committee for years was one of the world's foremost authorities on wines and the winemaking process, a professor of viticulture at the University of California, Davis.

The Grove Committee was first formed in 1900 when the club finally purchased the land it had been using for many of its encampments since 1880. The Grove Committee has to oversee the maintenance of the many buildings which have been added to the site, including the beautifully designed Grove Clubhouse that overlooks the river, built in 1904. Additionally, there is a parking lot which must be continually enlarged, wells that have to be deepened, and a dispensary that has to have medical supplies (for example, 370 people checked into the dispensary for one small thing or another in 1970, but two people died, one at the Grove, one in an ambulance on the way to San Francisco). The committee also has to have the Grove ready for such activities as the Spring Jinks (a weekend of entertainment), the June Picnic (when members bring their wives to the Grove for a Saturday afternoon), and private parties by members. Thousands of people visit the Grove between encampments for one occasion or another.

The Jinks Committee and the House and Restaurant Committee have a common concern: encouraging a large enough attendance at luncheons and entertainments to pay the financial bills. With costs going up all the time, there is a fear that club operations will slip into the red. "To put it simply, we need more people using the club at lunch time," says an annual report of the House and Restaurant Committee. "Our luncheon business has dropped off for many reasons, and great effort will be put forth in the future by the new committee, we trust, to induce the membership to come to lunch at the club more often.

The Jinks Committee constantly worries over attendance at the programs it puts on at the downtown clubhouse during the year. "They have to reach a minimum attendance or they're in trouble," says my informant close to Jinks operations. "The question always is -- will a given play or show draw well? Will 400 or so people show up for dinner and drinks?" In short, the Bohemian Club is a large enough institution to have needs of its own. Leaders have to devise ways of tempting members to come to the club more often -- so that the needs of the institution can be met. The club no longer merely serves the needs of its members. Now the members must serve the needs of the club.

The Membership Committee is the major gatekeeper of the Bohemian Club, for membership is of course by invitation only. A potential member must be nominated by at least two regular members of the club who will vouch for his character and describe the qualities that will make him a "good Bohemian." (However, honorary associates, those who have reached a retirement age, are allowed to sponsor applicants for associate membership, which means new performing members can be recruited more readily.) The prospect himself must fill out a membership application form obtained for him by his sponsors. The form requests the usual information necessary on any application for credit or a license, along with such tidbits as wife's maiden name, business or professional connections, other club memberships, and the names of five people in the club who know him. The hopeful candidate then returns this membership application to his first sponsor, who fills out a part of it which asks for information on "musical, oratorical, literary, artistic, or histrionic talents." This sponsor also provides the names of three members of the club who are known by him to be well acquainted with the applicant. Next the form goes to the second sponsor, who answers the same questions as the first sponsor in addition to listing five members of the club to whom the applicant is personally known.

The prospect then makes appointments to see individually the members of the Membership Committee. He goes by their places of business or law to be asked questions about why he wants to become a member of the Bohemian Club, but even more to be lectured by them about what it means to be a "good Bohemian."

In the meantime, the Membership Committee has been soliciting letters of recommendation about the candidate from some or all of the club members suggested by the candidate and his sponsors as people who know him well. The committee also circulates a monthly notice to all club members, listing people being considered for membership and asking for any opinions (positive or negative) anyone might have on any of the people listed. The notice lists the person's name, age, occupation, and sponsors. Finally, after this rigorous screening, there is the vote. Nine of the eleven members of the Membership Committee have to favor the candidate before he can become a member. Three negative votes and he has to wait at least three years before being proposed again.

Gaining the necessary votes does not make a person automatically a member, however, for there is a long waiting list. Many hundreds of people are backed up to become regular resident members. I talked to one regular member who had been on the waiting list for over ten years before becoming a member.

New associate members have no trouble claiming their rightful place -- there are no waiting lists for men of talent. "And if you are jinks material, which means you'll write or perform in Grove plays and shows, then they'll zip you right through," says one informant familiar with jinks operations. It is not surprising that the club constantly searches for jinks material. The talented members not only have the two-week encampment to plan for, but they must put on some kind of performance every Thursday night from October to May. "Over the years," says the club handbook, "the demands on the talented members of the Club have increased tremendously with three major productions and 12 Campfire or related programs during the Encampment and 20 or more Thursday nights in the City Club with five or six of these listed as major events."

Even this brief overview of the club and its activities makes clear that it is a 24-hour, 12-months-a-year operation. As a recent president used to say in his letter of congratulations to new members, "You have joined not only a club, but a way of life."

The highlight of a Grove encampment is an opening day initiation ceremony called "The Cremation of Care," in which the campers are given permission to forget their worldly duties and responsibilities, and instead focus on having a good time, just like in the old days, when they were young and supposedly carefree. Although the ceremony is very elaborate and has a long tradition, readers have to understand at the outset that it is a lark, a spoof of ceremonies, that has no deep or serious intent, contrary to what some conspiracy theorists have claimed. It is just what it claims to be: a way to ease everyone into a mood where they can relax and enjoy themselves. The scenario unfolds something like this:

The boys begin to arrive at the Bohemian Grove on the Saturday closest to the middle of July for what will be a two-week encampment. In actuality, most of them will just attend during one or two of the three weekends included in the encampment, jetting in to the nearby Santa Rosa airport from all over the country, or driving up from San Francisco.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

As they arrive, they first get settled at their camps, then wander around visiting with old friends. That night they have their first dinner in the huge open-air dining circle. They hear flowery welcoming speeches, they give a cheer to the "Old Guard," those who have been in the club for 40 or more years, and they pay their respects to the "Fallen Leaves," those who have died in the past year.

But the highlight of the evening is the Cremation of Care, an initiation into the spirit of the encampment. It is all very fancy. The script varies only slightly each year. It is also a put-on, a mock of rituals -- but it is a ritual ceremony nonetheless. Postmodernists might call it a meta-ritual. It is meant to signal that the encampment is a time for relaxation, drinking, and fun. It is a return to the summer camp days of their youth.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

To gain a sense of what it's like to take part, imagine yourself comfortably seated in the beautiful open-air dining hall. It's early evening and the clear July air is still pleasantly warm. Dusk has descended, you have finished a sumptuous dinner, and you are sitting quietly with your drink, listening to the nostalgic welcoming speeches and enjoying the gentle light and the eerie shadows that are cast by the two-stemmed gaslights flickering softly at each of the several hundred outdoor banquet tables.

You are part of an assemblage that has been meeting in this redwood grove 65 miles north of San Francisco for well over a hundred years. It is not just any assemblage, for you are a captain of industry, a well-known television star, a banker, a famous artist, or maybe a member of the President's cabinet. You are one of 1,500 men -- women are not allowed -- gathered together from all over the country for this annual encampment of the rich and the famous. And you are about to take part in a strange ceremony that has marked every Bohemian Grove gathering since 1880.

Out of the shadows on one of the hillsides near the dining circle there emerges the low, sad sounds of a funeral dirge. As you turn your head in its direction you faintly see the outlines of men dressed in pointed red hoods and red flowing robes. Some of the men are playing the funereal music; others are carrying long torches whose flames are a spectacular sight against the darkened forest.

As the procession approaches the dining circle, the dim figures become more distinct, and attention fixes on several men not previously noticed. They are carrying a large wooden box. Upon closer inspection the box turns out to be an open coffin, and in that coffin is a body, a human body that looks real enough to be lifelike at a glance, but only an imitation, naturally, made of black muslin wrapped around a wooden skeleton. This is the body of Care, symbolizing the concerns and woes that important men supposedly must bear in their daily lives. It is this guy, Mr. Dull Care, who is to be cremated this first Saturday night of the two-week encampment of the Bohemian Grove.

The cortege now trails slowly past the dining area, and the men in the dining circle fall into line behind the hooded priests and pallbearers, following the body of Care toward its ultimate destination. The entire parade (mostly white, mostly elderly) makes its way along a road leading to a picturesque little lake that is yet another of the sylvan sights the Bohemian Grove has to offer.

It takes the communicants about five minutes to make their march to this new setting. Once at the lake the several priests and the body of Care go off to the right, in the direction of a very large altar which faces the lake. They are accompanied by a cast of 250 elders, torchbearers, shore patrols, fire tenders, production managers, and woodland voices.

The major parts in this drama are played by "associate" or "performing" members of the club, middle-class men with musical, theatrical, artistic, or literary talents. But sometimes very important men have small walk-on roles that show they are just one of the gang when they are at the Bohemian Grove. They are "carrying a spear for Bohemia," as the saying goes, which means they are chipping in, doing their part, being good sports.

If the year were 1996, there would be three spear-carriers doing a little add-on part. They are former president George H. W. Bush, actor Clint Eastwood, and fabled news anchor Walter Cronkite. They are playing the parts of "Lakeside Frogs," and they are chanting like the frogs in the famous "Bud-WEI-ser" TV ads of the 1990s, only they keep croaking "cre-MAY-shun, cre-MAY-shun, cre-MAY-shun."

|

| (click to enlarge) |

The followers, talking quietly and remarking on the once-again-perfect Grove weather, move to the left so they can observe the ceremony from a green meadow on the other side of the lake. Drinks in hand, they will be about fifty to a hundred yards from the altar, which looms skyward thirty to forty feet and reveals itself to be in the form of a huge Owl, whose cement shell is mottled with primeval green mosses. This Owl is the totem animal of Bohemia, found not only at the lake, but everywhere you go in the Grove, and on shot glasses, coffee cups, and stationery.

While the spectators seat themselves across the lake, the priests and their entourage continue for another two or three hundred yards beyond the altar to a boat landing. There the bier is carefully transferred onto the Ferry of Care, which will carry the body to the altar later in the ceremony. Once the ferry is loaded, the torches are extinguished and the music ends. The attention of the spectators on the other side of the lake slowly drifts back to the Owl shrine; it is illuminated by a gentle flame from the Lamp of Fellowship, which sits at its base.

Cremation? A guy named Dull Care? A former president of the United States playing the part of a frog and chanting "cre-MAY-shun?" A totem animal and a Lamp of Fellowship? Strange, but true. You are starting to get the picture of just how hokey this all is.

People who have seen the ceremony before nudge you to keep your eye on the large redwood next to the Owl. Moments later an offstage chorus of "woodland voices" begins to sing. Then a spotlight illuminates the tree you've been watching, and there emerges from it a hamadryad, a "tree spirit," whose life, according to Greek mythology, is intimately bound up with the tree in which it lives. The hamadryad begins to sing, telling the supplicants that beauty and strength and peace are theirs as long as the trees of the Grove are there. It sings of the "temple-aisles of the wood" that are made for "your delight," and implores the Bohemians to "burn away the sorrow of yesterday" and to "cast your grief to the fires and be strong with the holy trees and the spirit of the Grove."'

With the end of this uplifting song, the hamadryad returns to its tree, the chorus silences, and the light on the tree fades out. Now there's only natural illumination from the moon and stars, and it's time for the high priest and his many assistants to enter the large area in front of the Owl.

"The Owl is in his leafy temple," intones the high priest. "Let all within the Grove be reverent before him." He beseeches the spectators to be inspired and awed by their surroundings, noting that this is Bohemia's shrine. Then he invokes the motto of the club, "Weaving spiders, come not here!" That's a line from Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream"; it is supposed to warn members not to discuss business and worldly concerns, and instead concentrate on the arts, literature, and other pleasures within the portals of Bohemia.

The priest next walks down three large steps to the edge of the lake. There he makes a flowery speech about the ripple of waters, the song of birds, the forest floor, and evening's cool kiss. Again he calls on the members to forsake their usual concerns: "Shake off your sorrows with the City's dust and scatter to the winds the cares of life." A second and third priest then recall to memory deceased friends who loved the Bohemian Grove, and the high priest makes yet another effusive speech, the gist of it being that "Great Nature" is a "refuge for the weary heart" and a "balm for breasts that have been bruised."

The pace is picking up. A brief song is sung by the chorus and suddenly the high priest proclaims: "Our funeral pyre awaits the corpse of Care!" A horn is sounded at the boat landing. Behold, the Ferry of Care, with its beautifully ornamented frontispiece, begins its brief passage to the foot of the shrine. Its trip is accompanied by the music of a barcarole (a barcarole is the song of Venetian gondoliers as they pole through the canals of Venice). Listening to the barcarole, it becomes ever more clear how many little extra bits and pieces of culture have been borrowed from many parts of the world by the Bohemians who lovingly developed this ritual over its long history.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

The bier arrives at the steps of the altar. The high priest inveighs against Dull Care, the archenemy of Beauty. He shouts, "Bring fire," and the torchbearers enter (18 strong). Then the acolytes quickly seize the coffin, lift it high above their heads, and carry it triumphantly to the pyre in front of the mighty Owl. It seems that Care is about to be consumed by flames.

Ah, but not yet. Suddenly there is a great clap of thunder and a rush of wind. Peals of loud, ugly laughter come ringing down from a hill above the lake. A dead tree is illuminated in the middle of the hillside, and Care himself bellows forth with a thundering blast:

"Fools! Fools! Fools! When will ye learn that me ye cannot slay? Year after year ye burn me in this Grove, lifting your puny shouts of triumph to the stars. But when again ye turn your feet toward the marketplace, am I not waiting for you, as of old? Fools! Fools! To dream ye conquer Care!"

The high priest is taken aback by this impressive outburst, but not completely humbled. He replies that it is not all a dream, that he and his friends know they will have to face Care when their holiday is over. They are happy that the good fellowship created by the Bohemian Grove is able to banish Care even for a short time. So the high priest tells Care, "We shall burn thee once again this night and in the flames that eat thine effigy we'll read the sign: Midsummer sets us free."

|

| (click to enlarge) |

Dull Care, however, is having none of this. He tells the high priest in no uncertain terms that priestly fires are not going to do him in. "I spit upon your fire," he roars, and with that there is a great explosion and all the torches are immediately extinguished. The only light remaining comes from the small flame in the Lamp of Fellowship.

Things are clearly at an impasse. Care may win out after all. There is only one thing to do: turn to the great Owl, the great totem animal of Bohemia, chosen as the group's symbol primarily for its mortal wisdom -- and only secondarily for its discreet silence and its nightly prowling. The high priest falls to his knees and lifts his arms toward the shrine. "Oh thou, great symbol of all mortal wisdom," he cries. "Owl of Bohemia, we do beseech thee, grant us thy counsel!"

The inspirational music of the "Fire Finale" now begins, and an aura of light glows about the Owl's head. The Owl is going to rise to the occasion! And if it's the 1990s, it's none other than the voice of good old Walter Conkrite, although the part usually goes to a deep-voiced drama professor. After a pause, the sagacious bird finally speaks. No fire, he tells the assembled faithful, can drive out Care if that fire comes from the mundane world, where it is fed by the hates of men. There is only one fire that can overcome the great enemy Care, and that, of course, is the flame which burns in the Lamp of Fellowship on the Altar of Bohemia. "Hail, Fellowship," he concludes, "and thou, Dull Care, begone!"

The priest smacks himself on the side of the head, as if to say he wonders why he didn't think of that profound point. The light goes out on the dead tree. The high priest leaps to his feet and bounds up the steps, snatches a burned-out torch from one of the bearers, and relights it from the flame of the Lamp of Fellowship. Just as quickly he ignites the funeral pyre and triumphantly hurls the torch into the blaze.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

The orchestral music in the background intensifies as the flames leap higher and higher. The chorus sings loudly about Dull Care, archenemy of Beauty, calling on the winds to make merry with his dust. "Hail, Fellowship," they sing, echoing the Owl. "Begone, Dull Care! Midsummer sets us free!" The wailing voice of Care gives its last gasps, the music gets even louder, and fireworks light the sky and fill the Grove with the reverberations of great explosions. The band, appropriately enough, strikes up "There'll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight." Care has been banished.

As this climax approaches, some 50 minutes after the march began, the quiet onlookers on the other side of the lake begin to come alive. After all, it is a night for rejoicing. The men begin to shout, to sing, to hug each other, and dance around. They have been freed by their priests and their Owl for some good old-fashioned hell raising. They couldn't be happier if they were back in college and their fraternity had won an intramural football championship.

Now the ceremony is over. The revelers, initiated into the carefree attitude of the Bohemian Grove, break up into small groups as they return to the camps that crowd next to each other in the central area of the Grove. It will be a night of storytelling and drinking for the men of Bohemia as they sit around their campfires or wander from camp to camp, renewing old friendships and making new ones. They will be far away from their responsibilities as the decision makers and opinion molders of corporate America.

It's straight out of tribal life the world over. No women. Lots of drinking and boasting. Men will be men, and boys will be boys.

The Cremation of Care is the most spectacular event of the midsummer retreat, but there are several other entertainments as well. Before the Bohemians return to the everyday world, they will be treated to plays, variety shows, song fests, shooting contests, art exhibits, swimming, boating, and nature rides. Of all these delights, the most elaborate are the two Jinks: High Jinks and Low Jinks.

Among Bohemians, planned entertainment of any real magnitude is called a Jinks. This nomenclature comes from the earliest days of the club, when its members were searching for precedents and traditions to adopt from the literature and entertainment of other times and other places. In the case of Jinks, they had found a Scottish word which denotes, generally speaking, a frolic, although it also was used in the past to refer to a drinking bout which involved a matching of wits to see who paid for the drinks. Bohemian Club historiographers, however, claim the word was gleaned from a more respectable source, Guy Mannering, a novel by Sir Walter Scott; there the High Jinks are a more elevated occasion, with drinking only a subsidiary indulgence.

The early Jinks at the Grove slowly developed into more and more elaborate entertainments. Already by 1902 the High Jinks had become what it is today, a grandiose, operetta-like extravaganza written and produced by club members for its one-time-only presentation in the Grove. The High Jinks, which is presented on the Friday night of the last weekend, is considered the most important formal event of the encampment.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

Most of the plays written for the High Jinks have a mythical or fantasy theme, although a significant minority have a historical setting. Any moral messages center on inevitable human frailty, not social injustice. There is no spoofing of the powers-that-be at a High Jinks; it is strictly a highbrow occasion. A few titles give the flavor: The Man in the Forest, The Cave Man , The Fall of Ug, The Rout of the Philistines, The Golden Feather, Johnny Appleseed, A Jest of Robin Hood, Rip Van Winkle, The Bonnie Cravat, The Fall of Pompeii.

A priest, of all unlikely people, holds the honor of being the only person to be the subject of two Grove plays. He is the Patron Saint of Bohemia, Saint John of Nepomuck (pronounced NAY-po-muk), a man who lived in the thirteenth century in the real Bohemia that is now part of Czechoslovakia. Saint John received his unique distinction among latter-day Bohemians in 1882, when his sad but courageous story was told in a jinks "sired" (the club argot for master of ceremonies) by the poet Charles Warren Stoddard.

Saint John was a cutup in his youth, but had forsaken ephemeral pleasures -- or at least most of them -- for the priesthood. One of his first assignments was as a tutor to the heir apparent to the kingship of Bohemia. John soon became fast friends with the fun-loving prince, often joining him in his spirited and amorous adventures. When the prince became king, he made Saint John the court confessor.

All went well for Saint John until the king began to suspect that his beautiful queen was having a love affair with a local nobleman. To allay his suspicions, the king naturally turned to his loyal friend and teacher, Saint John of Nepomuck, demanding that this former companion in many revelries reveal to him the most intimate confessions of the queen. Saint John refused. The king pleaded, but to no avail. Then the king threatened him, which had no effect either. Finally, in a fit of rage, he ordered Saint John hurled into the river to drown. John chose to die rather than reveal a woman's secrets. Here, truly, was a remarkable fellow, and his story appealed mightily to the San Francisco Bohemians of the nineteenth century.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

Several months after the poet Stoddard introduced Saint John to his fellow Bohemians, a small statue of Saint John arrived at the clubhouse in San Francisco from faraway Czechoslovakia. It seems one of the people present for Stoddard's talk had been Count Joseph Oswald Von Thun of Czechoslovakia, who had been much taken by the club and its appreciation of his fellow countryman. Upon his return to Czechoslovakia be had commissioned a woodcarver to make a replica of the statue of Saint John which adorns the bridge in Prague near the place of his drowning.

This unexpected gift still guards the library room in the Bohemians' large club building in San Francisco -- except during the encampment at the Grove, that is. For that event the statue is carefully transported to a hallowed tree near the center of the Grove, where Saint John, with his forefinger carefully sealing his lips, can be a saintly reminder of the need for discretion.

The legend surrounding Saint John of Nepomuck became part of the oral tradition of the Bohemian Club. New members inevitably hear the story when they happen upon the statue while being shown around the city clubhouse or the Grove. But oral tradition is not enough for a patron saint, and the good man's legend was therefore enacted in a Grove play in 1921 under the title St. John of Nepomuck. It was retold in 1969 by a different author under the title St. John of Bohemia.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

How good are the Grove plays? "Pretty darn good," says one member who knows theater. He thinks maybe one in ten High Jinks would be a commercial success if produced for outside audiences. Another member is not so sure about their general appeal. "They're damned fine productions," he claims, "but they are so geared to the special features of a Grove encampment, and so full of schmaltz and nostalgia, that it's hard to say how well they'd go over with ordinary audiences."

Whatever the quality, the plays are enormously elaborate productions, with huge casts, large stage sets, much singing, and dazzling lighting effects. "Hell, most stages wouldn't hold a Grove production," said our second informant. "That Grove stage is about ten thousand square feet, and there are all sorts of pathways leading into it from the hillside behind it. Not to mention the little clearings on the hillside which are used to great effect in some plays."

|

| (click to enlarge) |

A cast for a typical Grove play easily runs to seventy-five or one hundred people. Add in the orchestra, the stagehands, the carpenters who make the sets, and other supporting personnel, and over three hundred people are involved in creating the High Jinks each year. Preparations begin a year in advance, with rehearsals occurring two or three times a week in the month before the encampment, and nightly in the week before the play.

Costs are on the order of $130,000 to $150,000 per High Jinks in 2004 dollars, a large amount of money for a one-night production which does not have to pay a penny for salaries (the highest cost in any commercial production). "And the costs are talked about, too," reports my second informant. "'Hey, did you hear the High jinks will cost $150,000 this year?' one of them will say to another. The expense of the play is one way they can relate to its worth."

The High Jinks is the pride of the Grove, but a little highbrow stuff goes a long way among clubmen, even clubmen who like to think of themselves as cultured. From the early beginnings of the club, the High Jinks has been counterbalanced by the more slapstick and ribald fun of Low Jinks. For many years the Low Jinks were basically haphazard and extemporaneous, but slowly they too became more elaborate and professional as the Grove grew from a few campers on a weekend holiday to a full-blown two-week encampment which requires year-round planning and maintenance. Now the Low Jinks is a specially written musical comedy requiring almost as much attention and concern as the High Jinks. Personnel requirements are slightly less-perhaps 200-250 people to the 300-350 needed for High Jinks. Costs also are half or less than for a High Jinx.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

The subject matter of the Low Jinks is very different from that of the High Jinks. The title of the first formal Low Jinks in 1924 was The Lady of Monte Rio, which every good Bohemian would immediately recognize as an allusion to the ladies of the evening who are available in certain inns and motels near the Grove. The 1968 Low Jinks concerned "The Sin of Ophelia Grabb" (whose program is pictured here), a vulgar play on words if there ever was one. Ophelia lived with Letchwell Lear in unwedded bliss even though she was the daughter of the mayor of Shady Corners. "Thrice Knightly," another recent Low Jinks, also needs no explanation, especially to old fraternity boys who know that "once a king always a king, but once a knight is enough."

|

| (click to enlarge) |

Since there are no women allowed in the Bohemian Club, men have to dress in drag and play women's parts. (An example from a 1957 production is pictured here.) In 1989 a male member of the cast called the burly men playing the parts of women "heifers," which soon led the audience to moo each time the heifers appeared on the stage.

The Cremation of Care, the High Jinks, and the Low Jinks are productions involving hundreds of ordinary Bohemian Club members. They require planning, coordination, and money, and Bohemians are proud of the fact that they are part of a club which creates its own theatrical enjoyments. However, the Bohemians are not averse to enjoying professional entertainment by stars of stage, screen, and television. For this, there are the Little Friday Night and the Big Saturday Night.

The Little Friday Night is held on the second weekend of the encampment. The Big Saturday Night is on the third weekend-it closes the encampment. Both are shows made up of acts put on by famous stars. All of this talent is free, of course. No one would think of asking for money to perform for such a select audience, and if anyone should think to ask, he immediately would be dis-invited. People are supposed to understand it is an honor to entertain those in attendance at the Bohemian Grove.

Formal Grove shows and informal camp shenanigans do not exhaust the possibilities of the Bohemian Grove. Members can find a number of other ways to amuse themselves.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

Some wander about quietly, drink in hand, enjoying the redwood trails. Others walk down the River Road to look at the meandering water of the Russian River 150 feet below; often they take the winding path down to the river and its beach, where they sit on the large beach deck, wade in the shallow water along the banks, swim in the specially developed swimming hole, or even paddle out in one of the Grove canoes.

Others can be found taking part in the skeet shooting and trap shooting that are provided. Some take regularly scheduled "rim rides" on Grove buses, journeying to the more distant parts of the Grove's several thousand acres while a tour guide recounts the natural history of the area. Many plan their late morning visit to the Civic Center (a group of small buildings which serve as message center, barber shop, and drug store) so they can make it to the noon organ concert which is held each day by the lake. (Seated at the base of the Owl Statue, the Bohemian band and the Bohemian orchestra each perform one afternoon concert during the encampment.)

|

| (click to enlarge) |

A pleasant afternoon can be spent at the Ice House, the beautiful redwood building that houses an annual art exhibit made up of paintings, photographs, and sculpture created by Bohemian Club members. Over three hundred original works of art are usually available for viewing. For evenings without large productions, there are less formal Campfire Circle entertainments featuring the band, the orchestra, the chorus, or individual storytellers and entertainers.

Skeet shooting, hiking, swimming, art exhibitions -- there is plenty to see and do in the Bohemian Grove even when a big production is not being staged. It is truly a place of many delights. But, despite all these attractions, it remains most of all a place to rest and relax in the company of friends.

Entertainment is not the only activity at the Bohemian Grove. For a little change of pace, there is intellectual stimulation and political enlightenment every day at 12:30 p.m. Since 1932 the meadow from which people view the Cremation of Care also has been the setting for informal talks and briefings by people as varied as entertainers, professors, astronauts, business leaders, cabinet officers, future presidents, and former presidents.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

The cabinet officers, politicians, generals, and governmental advisers are the rule rather than the exception on weekends. Figures from the worlds of art, literature, and science are more likely to make their appearance during the weekdays of the encampment, when Grove attendance may drop to four or five hundred (since the 1960s many of the members only come to the Grove for the weekends because they cannot stay away from their corporations and law firms for the full two weeks).

Members vary as to how interesting and informative they find the Lakeside Talks. Some find them useful, others do not, probably depending on their degree of familiarity with the topic being discussed. It is fairly certain that no inside or secret information is divulged, but a good feel for how a particular problem will be handled is likely to be communicated. Whatever the value of the talks, most members think there is something very nice about hearing official government policy, orthodox big-business ideology, and new scientific information from a fellow Bohemian or one of his guests in an informal atmosphere where no reporters are allowed to be present.

Politicians apparently find the Lakeside Talks especially attractive. "Giving a Lakeside" provides them with a means for personal exposure without officially violating the injunction "Weaving spiders, come not here." After all, Bohemians rationalize, a Lakeside Talk is merely an informal chat by a friend of the family.

Some members, at least, know better. They realize that the Grove is an ideal off-the-record atmosphere for sizing up politicians. "Well, of course when a politician comes here, we all get to see him, and his stock in trade is his personality and his ideas," a prominent Bohemian told a New York Times reporter who was trying to cover Nelson Rockefeller's 1963 visit to the Grove for a Lakeside Talk. The journalist went on to note that the midsummer encampments "have long been a major showcase where leaders of business, industry, education, the arts, and politics can come to examine each other."'

There's no better witness to the importance of Lakeside Talks than President Richard M. Nixon. He accords them a prominent role in his memoirs, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon (Grosset & Dunlap, 1978). He begins with an account of future President Dwight D. Eisenhower's appearance at the Grove. After noting he had met Ike briefly in 1948, he says that he had a chance to take his measure when the well-liked general came to the Bohemian Grove to give a Lakeside Talk:

"In the summer of 1950, I saw him at even closer quarters at the Bohemian Grove, the site of the annual summer retreat of San Francisco's Bohemian Club, where each year members of this prestigious private men's club and their guests from all over the country gather amidst California's beautiful redwoods. Herbert Hoover used to invite some of the most distinguished of the 1,400 men at the Grove to join him at his "Cave Man Camp" for lunch each day. [Nixon was a member, too.] On this occasion Eisenhower, then president of Columbia University, was the honored guest. Hoover sat at the head of the table as usual, with Eisenhower at his right. As the Republican nominee in an uphill Senate battle, I was about two places from the bottom."

"Eisenhower was deferential to Hoover but not obsequious. He responded to Hoover's toast with a very gracious one of his own. I am sure he was aware that he was in enemy territory among this generally conservative group. Hoover and most of his friends favored Taft and hoped that Eisenhower would not become a candidate. Later that day, Eisenhower spoke at the beautiful lakeside amphitheatre. It was not a polished speech, but he delivered it without notes and he had the good sense not to speak too long. The only line that drew significant applause was his comment that he did not see why anyone who refused to sign a loyalty oath should have the right to teach in a state university."

"After Eisenhower's speech we went back to Cave Man Camp and sat around the campfire appraising it. Everyone liked Eisenhower, but the feeling was that he had a long way to go before he would have the experience, the depth, and the understanding to be President. But it struck me forcibly that Eisenhower's personality and personal mystique had deeply impressed the skeptical and critical Cave Man audience." (page 80-81 of the Nixon memoirs)

Nixon next refers to Lakeside Talks in the context of his second run at the presidency in 1967. He was now suspect goods after failing to win in 1960, so he had to prove himself all over again. A Lakeside Talk was a key setting, the start of his comeback, he says:

"If I were to choose the speech that gave me the most pleasure and satisfaction in my political career, it would be my Lakeside Speech at the Bohemian Grove in July 1967. Because this speech traditionally was off the record it received no publicity at the time. But in many important ways it marked the first milestone on my road to the presidency."

"The setting is possibly the most dramatic and beautiful I have ever seen. A natural amphitheatre has been built up around a platform on the shore of a small lake. Redwoods tower above the scene, and the weather in July is usually warm and clear. Herbert Hoover had always delivered the [last] Lakeside Speech [of the encampment], but he had died in 1964, and I was asked if I would deliver the 1967 speech in his honor. It was an emotional assignment for me and also an unparalleled opportunity to reach some of the most important and influential men, not just from California but from across the country. In the speech I pointed that that we live in a new world -- 'never in human history have more changes taken place in the world in one generation' -- and that this is a world of new leaders, of new people, of new ideas." [As if we haven't heard that before, including the current generation. It is always so new, always more critical than before, but in fact it is more similar than different -- GWD].

"I led the audience on a tour of the world, tracing the changes and examining the conflicts, finding both danger and opportunity as the United States entered the final third of the twentieth century. I urged the need for strong alliances and continued aid to the developing nations, but I also urged that we should provide our aid more selectively, rewarding our friends and discouraging our enemies and encouraging private rather than government enterprise."

"Turning to the Soviet Union, I noted that even as the Soviet leaders talked peace they continued to stir up trouble, to encourage aggression. and to build missiles. I urged that we encourage trade with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and that 'diplomatically we should have discussions with the Soviet leaders at all levels to reduce the possibility of miscalculation and to explore the areas where bilateral agreements would reduce tensions.' But we should insist on reciprocity: 'I believe in building bridges but we should build only our end of the bridge.' And in negotiations we must always remember "that our goal is different from theirs. We seek peace as an end in itself. They seek victory, with peace being at this time a 'means toward that end.'"

"Looking ahead, I said: 'As we enter this last third of the twentieth century the hopes of the world rest with America. Whether peace and freedom survive in the world depends on American leadership. Never has a nation had more advantages to lead. Our economic superiority is enormous; our military superiority can be whatever we choose to make.'" (page 284)

But rehabilitation through a Lakeside Talk was not all Nixon accomplished at the Bohemian Grove that summer. He also had a "candid discussion" with Ronald Reagan "as we sat outdoors on a bench under one of the giant redwoods." Nixon told Reagan of his plans to enter the primaries. He assured Reagan he would not campaign against any "fellow Republicans." Reagan allegedly professed surprise that there was speculation about his possible candidacy, and claimed he did not want to be a favorite son. According to Nixon, Reagan said "that he would not be a candidate in the primaries." In other words, they came to a deal at the Grove, with Reagan saying he would only enter the primaries if Nixon faltered.

Nixon was so full of himself over the Bohemian Grove, and so pleased to be a member, that he actually wanted to give a Lakeside Talk in 1971 even though he was now the president of the United States. After he got himself an invitation, and the press heard about it, a flap developed, as revealed to me by one of my informants, who was the Grove telephone operator at the time. The press was not about to let the president of the United States disappear into a redwood grove for an off-the-record speech to some of the most powerful men in America. It objected loudly and vowed to make every effort to cover the event, The publicity caused the club considerable embarrassment, and after much hemming and hawing back and forth, the club leaders asked the President to cancel his schedule appearance. A White House press secretary then announced that the President had decided not to appear at the Grove rather than risk the tradition that speeches there are strictly off the public record.

However, Nixon was not left without a final word to his fellow Bohemians. In a telegram to the president of the club, which used to hang at the entrance to the reading room in the San Francisco clubhouse, he expressed his regrets at not being able to attend. He asked the club president to continue to lead people into the woods, adding that he in turn would redouble his efforts to lead people out of the woods. He also noted that, while anyone could aspire to be President of the United States, only a few could aspire to be president of the Bohemian Club.

And yet, when his secret tapes were made available years later, it turns out he also badmouthed the Bohemians: "The Bohemian Club, which I attend from time to time -- is the most faggy goddamned thing you could ever imagine, with the San Francisco crowd. I can't shake hands with anybody from San Francisco." (As quoted in an article in the San Francisco Chronicle on July 18, 2004, page 1, "The Chosen Few," by Adair Lara. The quote is on pages A18-19)

|

| (click to enlarge) |

Turning to a few post-Nixon examples, the Grove had quite a line-up of Lakeside speakers in 1991, including the African-American lawyer Vernon Jordan, soon to be a prominent confidant of President Bill Clinton. Helmut Schmidt, the former chancellor of West Germany, also appeared (pictured), as did the then-Secretary of Defense, Richard Cheney. George Shultz, the Secretary of State under Reagan, gave a talk called "Agenda for America."

The 1994 encampment made news because of a nasty Lakeside attack on recently defeated President George H. W. Bush, a longtime Bohemian, by a former Secretary of Treasury, William Simon. Simon was a supercilious super-conservative who castigated Bush for allegedly abandoning the Reagan agenda. By that time Simon was a multi-millionaire many times over and a leader in creating the New Right.

|

| (click to enlarge) |

In 1995, House Speaker Newt Gingrich delivered the Lakeside Talk on the middle Saturday of the encampment, and former President Bush had his turn on the final Saturday (pictured). He used the occasion to say that his son George W. Bush would make a great president some day.

The featured Saturday speakers in 1996 were Pete Wilson, the Republican Governor of California, and a former Republican Secretary of State.

Perhaps the most striking change in the Lakeside Talks in the 1990s was the complete absence of any appointees from the Clinton Administration. In the past, cabinet members from the Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter administrations were prominent guests and Lakeside speakers. It is safe to say that the Bohemian Club's regular members are now solidly Republican.

So, yes, within the context of the goofing off, pranks, and drinking at the Bohemian Grove, some political business does get done. Republican business. But note that it involves jockeying among politicians for advantage, not serious policy discussions. The Grove is an occasion for some politicking, but it is only one of many such settings.

Not all the entertainment at the Bohemian Grove takes place under the auspices of the committee in charge of special events. The Bohemians and their guests are divided into camps which evolved slowly over the years as the number of people on the retreat grew into the hundreds and then the thousands. These camps have become a significant center of enjoyment during the encampment.

|

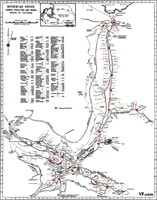

| Map of the Grove, courtesy of VanityFair.com (click to enlarge) |

At first the camps were merely a place in the woods where a half-dozen to a dozen friends would pitch their tents. Soon they added little amenities like their own special stove or a small permanent structure. Then there developed little camp traditions and endearing camp names like Cliff Dwellers, Moonshiners, Silverado Squatters, Woof, Zaca, Toyland, Sundodgers, and Land of Happiness. The next steps were special emblems, a handsome little lodge or specially constructed tepees, a permanent bar, and maybe a grand piano.

Today there are about 120 camps of varying sizes, structures, and statuses. Most have between 10 and 30 members, but there are one or two with about 125 members and several with less than 10. A majority of the camps are strewn along what is called the River Road, but some are huddled in other areas within five or ten minutes of the center of the Grove.