R. Buckminster Fuller c.1917

Milton, Massachusetts

Los Angeles, California, U.S.

| Buckminster Fuller | |

|---|---|

R. Buckminster Fuller c.1917 |

|

| Born | July 12, 1895 Milton, Massachusetts |

| Died | July 1, 1983 (aged 87) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Visionary, designer, architect, author, inventor |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Fuller |

| Children | 2 |

Richard Buckminster “Bucky” Fuller (July 12, 1895 – July 1, 1983)[1] was an American architect, author, designer, inventor, and futurist.

Fuller published more than thirty books, inventing and popularizing terms such as "Spaceship Earth", ephemeralization, and synergetics. He also developed numerous inventions, mainly architectural designs, the best known of which is the geodesic dome. Carbon molecules known as fullerenes were later named by scientists for their resemblance to geodesic spheres.

Contents[hide] |

Fuller was born on July 12, 1895, in Milton, Massachusetts, the son of Richard Buckminster Fuller and Caroline Wolcott Andrews, and also the grandnephew of the American Transcendentalist Margaret Fuller. He attended Froebelian Kindergarten. Spending much of his youth on Bear Island, in Penobscot Bay off the coast of Maine, he was a boy with a natural propensity for design and construction. He often made items from materials he brought home from the woods, and sometimes made his own tools. He experimented with designing a new apparatus for human propulsion of small boats. Years later, he decided that this sort of experience had provided him with not only an interest in design, but a habit of being familiar and knowledgeable about the materials that his later projects would require. Fuller earned a machinist's certification, and knew how to use the press brake, stretch press, and other tools and equipment used in the sheet metal trade.[2]

Fuller was sent to Milton Academy, in Massachusetts, and after that, began studying at Harvard. He was expelled from Harvard twice: first for spending all his money partying with a vaudeville troupe, and then, after having been readmitted, for his "irresponsibility and lack of interest". By his own appraisal, he was a non-conforming misfit in the fraternity environment.[2] Many years later, however, he would receive a Sc.D. from Bates College in Lewiston, Maine.

Between his sessions at Harvard, Fuller worked in Canada as a mechanic in a textile mill, and later as a labourer for the meat-packing industry. He also served in the U.S. Navy in World War I, as a shipboard radio operator, as an editor of a publication, and as a crash-boat commander. After discharge, he worked again for the meat packing industry, thereby acquiring management experience. During 1917, he married Anne Hewlett. During the early 1920s, he and his father-in-law developed the Stockade Building System for producing light-weight, weatherproof, and fireproof housing – although the company would ultimately fail.[2]

By age 32, Fuller was bankrupt and jobless, living in public, low-income housing in Chicago, Illinois. In 1922[3], Fuller's young daughter Alexandra died from complications from polio and spinal meningitis. Allegedly, he felt responsible and this caused him to become drunk frequently and to contemplate suicide for a while, but he decided instead to embark on "an experiment, to find what a single individual [could] contribute to changing the world and benefiting all humanity".[4]

By 1928, Fuller was living in Greenwich Village and spending much of time at Romany Marie's,[5] where he had spent a fascinating evening in conversation with Marie and Eugene O'Neill several years earlier.[6] Fuller accepted a job decorating the interior of the café in exchange for meals,[5] giving informal lectures several times a week,[6][7] and models of the Dymaxion house were exhibited at the café. Isamu Noguchi arrived during 1929 –Constantin Brâncuşi, an old friend of Marie's,[8] had directed him there[5] – and Noguchi and Fuller were soon collaborating on several projects,[7][9] including the modeling of the Dymaxion car.[10] It was the beginning of their lifelong friendship.

Fuller taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina during the summers of 1948 and 1949,[11] serving as its Summer Institute director in 1949. There, with the support of a group of professors and students, he began reinventing a project that would make him famous: the geodesic dome. Although the geodesic dome had been created some 30 years earlier by Dr. Walther Bauersfeld, Fuller was awarded US patents. He is credited for popularizing this type of structure. One of his early models was first constructed in 1945 at Bennington College in Vermont, where he frequently lectured. During 1949, he erected his first geodesic dome building that could sustain its own weight with no practical limits. It was 4.3 meters (14 ft) in diameter and constructed of aluminum aircraft tubing and a vinyl-plastic skin, in the form of an icosahedron. To prove his design, and to awe non-believers, Fuller hung from the structure’s framework several students who had helped him build it. The U.S. government recognized the importance of his work, and employed him to make small domes for the army. Within a few years there were thousands of these domes around the world.

For the next half-century, Fuller developed many ideas, designs and inventions, particularly regarding practical, inexpensive shelter and transportation. He documented his life, philosophy and ideas scrupulously by a daily diary (later called the Dymaxion Chronofile), and by twenty-eight publications. Fuller financed some of his experiments with inherited funds, sometimes augmented by funds invested by his collaborators, one example being the Dymaxion Car project.

International recognition began with the success of his huge geodesic domes during the 1950s. Fuller taught at Washington University in St. Louis in 1955, where he met James Fitzgibbon, who would become a close friend and colleague. From 1959 to 1970, Fuller taught at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Beginning as an assistant professor, he gained full professorship during 1968, in the School of Art and Design. Working as a designer, scientist, developer, and writer, he lectured for many years around the world. He collaborated at SIU with the designer John McHale. During 1965, Fuller inaugurated the World Design Science Decade (1965 to 1975) at the meeting of the International Union of Architects in Paris, which was, in his own words, devoted to "applying the principles of science to solving the problems of humanity".

Fuller believed human societies would soon rely mainly on renewable sources of energy, such as solar- and wind-derived electricity. He hoped for an age of "omni-successful education and sustenance of all humanity". For his lifetime of work, the American Humanist Association named him the 1969 Humanist of the Year.

Fuller was awarded 28 US patents[12] and many honorary doctorates. On January 16, 1970, he received the Gold Medal award from the American Institute of Architects. He also received numerous other awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom presented to him on February 23, 1983 by President Ronald Reagan.

Fuller's last filmed interview took place on April 3, 1983, in which he presented his analysis of Simon Rodia's Watts Towers as a unique embodiment of the structural principles found in nature. Portions of this interview appear in I Build the Tower, the definitive documentary film on Rodia's architectural masterpiece.

Fuller died on July 1, 1983, aged 87, a guru of the design, architecture, and 'alternative' communities, such as Drop City, the community of experimental artists to whom he awarded the 1966 "Dymaxion Award" for "poetically economic" domed living structures. During the period leading up to his death, his wife had been lying comatose in a Los Angeles hospital, dying of cancer. It was while visiting her there that he exclaimed, at a certain point: "She is squeezing my hand!" He then stood up, suffered a heart attack and died an hour later. His wife died 36 hours after he did. He is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The grandson of a Unitarian minister (Arthur Buckminster Fuller),[13] R. Buckminster Fuller was also Unitarian.[14] Buckminster Fuller was an early environmental activist. He was very aware of the finite resources the planet has to offer, and promoted a principle that he termed "ephemeralization", which, in essence – according to futurist and Fuller disciple Stewart Brand – Fuller coined to mean "doing more with less".[15] Resources and waste material from cruder products could be recycled into making more valuable products, increasing the efficiency of the entire process. Fuller also introduced synergetics, a metaphoric language for communicating experiences using geometric concepts, long before the term synergy became popular.

Buckminster Fuller was one of the first to propagate a systemic worldview, and he explored principles of energy and material efficiency in the fields of architecture, engineering and design.[16][17] He cited François de Chardenedes' opinion that petroleum, from the standpoint of its replacement cost out of our current energy "budget" (essentially, the net incoming solar flux), had cost nature "over a million dollars" per U.S. gallon (US$300,000 per litre) to produce. From this point of view, its use as a transportation fuel by people commuting to work represents a huge net loss compared to their earnings.[18]

Fuller was concerned about sustainability and about human survival under the existing socio-economic system, yet remained optimistic about humanity's future. Defining wealth in terms of knowledge, as the "technological ability to protect, nurture, support, and accommodate all growth needs of life," his analysis of the condition of "Spaceship Earth" caused him to conclude that at a certain time during the 1970s, humanity had attained an unprecedented state. He was convinced that the accumulation of relevant knowledge, combined with the quantities of major recyclable resources that had already been extracted from the earth, had attained a critical level, such that competition for necessities was not necessary anymore. Cooperation had become the optimum survival strategy. "Selfishness," he declared, "is unnecessary and hence-forth unrationalizable.... War is obsolete."[19]

Fuller also claimed that the natural analytic geometry of the universe was based on arrays of tetrahedra. He developed this in several ways, from the close-packing of spheres and the number of compressive or tensile members required to stabilize an object in space. One confirming result was that the strongest possible homogeneous truss is cyclically tetrahedral.[citation needed]

In his 1970 book I Seem To Be a Verb, he wrote: "I live on Earth at present, and I don’t know what I am. I know that I am not a category. I am not a thing — a noun. I seem to be a verb, an evolutionary process – an integral function of the universe."

|

|

This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2008) |

|

|

Fuller was most famous for his lattice shell structures - geodesic domes, which have been used as parts of military radar stations, civic buildings, environmental protest camps and exhibition attractions. However, the original design came from Dr. Walther Bauersfeld. Chapter 3 of Fuller's Book Critical Path states:

"....I found a similar situation to be existent in World War II. As head mechanical engineer of the U.S.A. Board of Economic Warfare I had available to me copies of any so-called intercepts I wanted. Those were transcriptions of censor-listened-to intercontinental telephone conversations, along with letters and cables that were opened by the censor and often deciphered, and so forth. As a student of patents I asked for and received all the intercept information relating to strategic patents held by both our enemies and our own big corporations,..."

An examination of the geodesic design by Bauersfeld for the Zeiss Planetarium, built some 20 years prior to Fuller's work, reveals that Fuller's Geodesic Dome patent (U.S. 2,682,235) follows the same methodology as Bauersfeld's design.[20]

Their construction is based on extending some basic principles to build simple "tensegrity" structures (tetrahedron, octahedron, and the closest packing of spheres), making them lightweight and stable. The patent for geodesic domes was awarded during 1954, part of Fuller's exploration of nature's constructing principles to find design solutions. The Fuller Dome is referenced in the Hugo Award-winning novel Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner, in which a geodesic dome is said to cover the entire island of Manhattan, and it floats on air due to the hot-air balloon effect of the large air-mass under the dome (and perhaps its construction of lightweight materials).[21]

Previously, Fuller had designed and built prototypes of what he hoped would be a safer, aerodynamic Dymaxion car. ("Dymaxion" is a syllabic abbreviation of dynamic maximum tension, or possibly of dynamic maximum ion as reported the National Automobile Museum.) Fuller worked with professional colleagues for three years beginning 1932. Based on a design idea Fuller had derived from aircraft, the three prototype cars were different from anything being sold. They had three wheels (two front drive wheels and one rear steered wheel. The engine was in the rear, and the chassis and body were original designs. The aerodynamic, somewhat tear-shaped body was large enough to seat 11 people. In one of the prototypes it was about 18 feet (5.5 m) long. It resembled a melding of a light aircraft (without wings) and a Volkswagen van of 1950s vintage. All three prototypes were essentially a mini-bus, and its concept long predated the Volkswagen Type 2 mini-bus conceived in 1947 by Ben Pon.

Despite its length, and due to its three-wheel design, the Dymaxion turned on a small radius and parked in a tight space quite nicely. The prototypes were efficient in fuel consumption for their day. Fuller contributed a great deal of his own money to the project, in addition to funds from one of his professional collaborators. An industrial investor was also very interested in the concept. Fuller anticipated the cars could travel on an open highway safely at up to about 160 km/h (100 miles per hour). But due to bad design, they were unruly above 80 km/h (50 mph), and difficult to steer. Research ended after one of the prototypes was involved in a collision resulting in a fatality.

During 1943, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser asked Fuller to develop a prototype for a smaller car, and Fuller designed a five-seater which was never developed further.

Another of Fuller's ideas was the alternative-projection Dymaxion map. This was designed to show Earth's continents with minimum distortion when projected or printed on a flat surface.

Fuller's energy-efficient and inexpensive Dymaxion House garnered much interest, but has never been produced. Here the term "Dymaxion" is used in effect to signify a "radically strong and light tensegrity structure". One of Fuller's Dymaxion Houses is on display as a permanent exhibit at The Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan. Designed and developed during the mid-1940s, this prototype is a round structure (not a dome), shaped something like the flattened "bell" of certain jellyfish. It has several innovative features, including revolving dresser drawers, and a fine-mist shower that reduces water consumption. According to Fuller biographer Steve Crooks, the house was designed to be delivered in two cylindrical packages, with interior color panels available at local dealers. A circular structure at the top of the house was designed to rotate around a central mast to use natural winds for cooling and air circulation.

Conceived nearly two decades before, and developed in Wichita, Kansas, the house was designed to be lightweight and adapted to windy climates. It was to be inexpensive to produce and purchase, and assembled easily. It was to be produced using factories, workers and technologies that had produced World War II aircraft. It was ultramodern-looking at the time, built of metal, and sheathed in polished aluminum. The basic model enclosed 90 m² (1000 square feet) of floor area. Due to publicity, there were many orders during the early Post-War years, but the company that Fuller and others had formed to produce the houses failed due to management problems.

During 1969, Fuller began the Otisco Project, named after its location in Otisco, New York. The project developed and demonstrated concrete spray technology used in conjunction with mesh covered wireforms as a viable means of producing large scale, load bearing spanning structures built in situ without the use of pouring molds, other adjacent surfaces or hoisting.

The initial construction method used a circular concrete footing in which anchor posts were set. Tubes cut to length and with ends flattened were then bolted together to form a duodeca-rhombicahedron (22 sided hemisphere) geodesic structure with spans ranging to 60 feet (18 m). The form was then draped with layers of ¼-inch wire mesh attached by twist ties. Concrete was then sprayed onto the structure, building up a solid layer which, when dried, would support additional concrete to be added by a variety of tradition means. Fuller referred to these buildings as monolithic ferroconcrete geodesic domes. The tubular frame form proved too problematic when it came to setting windows and doors, and was abandoned. The second method used iron rebar set vertically in the concrete footing and then bent inward and welded in place to create the dome’s wireform structure and performed satisfactorily. Domes up to 3 stories tall built with this method proved to be remarkably strong. Other shapes such as cones, pyramids and arches proved equally adaptable.

The project was enabled by a grant underwritten by Syracuse University and sponsored by US Steel (rebar), the Johnson Wire Corp, (mesh) and Portland Cement Company (concrete). The ability to build large complex load bearing concrete spanning structures in free space would open many possibilities in architecture, and is considered as one of Fuller’s greatest contributions.

Fuller was a frequent flier, often crossing time zones. He famously wore three watches; one for the current zone, one for the zone he had departed, and one for the zone he was going to.[22][23] Fuller also noted that a single sheet of newsprint, inserted over a shirt and under a suit jacket, provided completely effective heat insulation during long flights.

Fuller introduced a number of concepts, and helped develop others. Certainly, a number of his projects were not successful in terms of commitment from industry or acceptance by most of the public. However, more than 500,000 geodesic domes have been built around the world and many are in use. According to the Buckminster Fuller Institute Web site, the largest geodesic-dome structures are:

Other notable domes include:

However, contrary to Fuller's hopes, domes are not an everyday sight in most places. In practice, most of the smaller owner-built geodesic structures had disadvantages (see geodesic domes), including their unconventional appearance.

An interesting spin-off of Fuller's dome-design conceptualization was the Buckminster Ball, which was the official FIFA approved design for footballs (association football), from their introduction at the 1970 World Cup until recently. The design was a truncated icosahedron -- essentially a "Geodesic Sphere", consisting of 12 pentagonal and 20 hexagonal panels. This was used continuously for 34 years until it was replaced by a 14-panel version for the 2006 World Cup.

Fuller was followed (historically) by other designers and architects, such as Sir Norman Foster and Steve Baer, willing to explore the possibilities of new geometries in the design of buildings, not based on conventional rectangles.

|

|

Lists of miscellaneous information should be avoided. Please relocate any relevant information into appropriate sections or articles. (June 2008) |

The enormous Fuller Collection is currently housed at Stanford University.

Buckminster Fuller spoke and wrote in a unique style and said it important to describe the world as accurately as possible.[34] Fuller often created long run-on sentences and used unusual compound words (omniwell-informed, intertransformative, omni-interaccommodative, omniself-regenerative) as well as terms he himself invented.[35]

Fuller used the word 'Universe' without the definite or indefinite articles (a or the) and always capitalized the word. Fuller wrote that "by Universe I mean: the aggregate of all humanity's consciously apprehended and communicated (to self or others) Experiences." [36]

The words "down" and "up", according to Fuller, are awkward in that they refer to a planar concept of direction inconsistent with human experience. The words "in" and "out" should be used instead, he argued, because they better describe an object's relation to a gravitational center, the Earth. "I suggest to audiences that they say, "I'm going 'outstairs' and 'instairs.'" At first that sounds strange to them; They all laugh about it. But if they try saying in and out for a few days in fun, they find themselves beginning to realize that they are indeed going inward and outward in respect to the center of Earth, which is our Spaceship Earth. And for the first time they begin to feel real "reality." [37]

"World-around" is a term coined by Fuller to replace "worldwide". The general belief in a flat Earth died out in Classical antiquity, so using "wide" is an anachronism when referring to the surface of the Earth — a spheroidal surface has area and encloses a volume, but has no width. Fuller held that unthinking use of obsolete scientific ideas detracts from and misleads intuition. Other neologisms collectively invented by the Fuller family, according to Allegra Fuller Snyder, are the terms sunsight and sunclipse, replacing sunrise and sunset to overturn the geocentric bias of most pre-Copernican celestial mechanics. Fuller also invented the phrase Spaceship Earth.

Fuller also invented the word "livingry," as opposed to weaponry (or "killingry"), to mean that which is in support of all human, plant, and Earth life. "The architectural profession--civil, naval, aeronautical, and astronautical — has always been the place where the most competent thinking is conducted regarding livingry, as opposed to weaponry." — [38]

Fuller invented the term (but did not invent the concept of) "tensegrity", a portmanteau of tensional integrity. "Tensegrity describes a structural-relationship principle in which structural shape is guaranteed by the finitely closed, comprehensively continuous, tensional behaviors of the system and not by the discontinuous and exclusively local compressional member behaviors. Tensegrity provides the ability to yield increasingly without ultimately breaking or coming asunder" — [39]

"Dymaxion", is a portmanteau of "Dynamic maximum tension". It was invented by an adman about 1929 at Marshall Field's department store in Chicago to describe Fuller's concept house, which was shown as part of a house of the future store display. These were three words that Fuller used repeatedly to describe his design.

"The most important fact about Spaceship Earth: an instruction manual didn't come with it."[40]

His concepts and buildings include:

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Buckminster Fuller |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Buckminster Fuller |

|

|

This biography of a living person does not cite any references or sources. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living people that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately. (November 2008) Find sources: (J. Baldwin – news, books, scholar) |

James Tennant Baldwin (born 1934) (whose books and articles have been published under the names J. Baldwin, Jay Baldwin, and James T. Baldwin) is an American industrial designer and writer. Baldwin was a student of Buckminster Fuller; Baldwin's work has been inspired by Fuller's principles and (in the case of some of Baldwin's published writing) has popularized and interpreted Fuller's ideas and achievements. In his own right, Baldwin has been a figure in American designers' efforts to incorporate solar, wind, and other renewable sources of energy. In his career, being a fabricator has been as important as being a designer. Baldwin is noted as the inventor of the geodesic "Pillow Dome."

Contents[hide] |

J. Baldwin was born the son of an engineer. Baldwin has said that, at 18, he heard Buckminster Fuller speak for 14 hours non-stop. This was in 1951 at the University of Michigan, where Baldwin had enrolled to learn automobile design because a friend of his had been killed in a car accident that Baldwin attributed to bad design. He worked with Fuller prior to graduation from U. of M. in 1955. During his student years, Baldwin worked (in a unique job sharing role) in an auto factory assembly line. He went on to do graduate work at the University of California, Berkeley.

Baldwin remained a friend of Buckminster Fuller, and reflected that "By example, he encouraged me to think for myself comprehensively, to be disciplined, to work for the good of everyone, and to have a good time doing it." [BuckyWorks, p. xi]

As a young designer in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Baldwin designed advanced camping equipment with Bill Moss Associates. Thereafter, he taught simultaneously at San Francisco State College (now called San Francisco State University), San Francisco Art Institute, and the Oakland campus of California College of Arts & Crafts for about six years.

The period 1968-69 found him both a visiting lecturer at Southern Illinois University and the design editor of the innovative Whole Earth Catalog. (The Catalog came out in many editions between 1968 and 1998, and Baldwin continued to edit and write for both the Catalog and an offshoot publication, CoEvolution Quarterly, later renamed Whole Earth Review.) In the early 1970s, Baldwin taught at Pacific High School.

Baldwin was at the center of experimentation with geodesic domes (an unconventional building-design approach, explored by Fuller, that maximizes strength and covered area in relation to materials used). He also dove enthusiastically into the application of renewable energy sources in homes and in food-production facilities, working with Integrated Life Support Systems Laboratories (ILS, in New Mexico) and with Dr John Todd and the other New Alchemists involved with the "Ark" project. Baldwin's initial involvement with solar energy was during that very experimental, ad-lib phase when much was moving from principles or theory into actual development. In the 1970s, at ILS, he was the co-developer of what has been touted as the world's first building to be heated and otherwise powered by solar and wind power exclusively.

Baldwin referred to his own rural home as "a three-dimensional sketchpad."

During the Jerry Brown administration, Baldwin worked in the California Office of Appropriate Technology. Since the 1970s, Baldwin has continued to work as a designer in association with numerous organizations and projects. He organized for himself a mobile design studio and machine workshop (in a van pulling an Airstream trailer) to drive to various projects across America.

With the ears of a wider audience in the 1980s, Baldwin developed an incisive critique of the American automobile industry, which he viewed as over-focused on superficial marketing concerns and farcically under-concerned with real innovation and improvement. He was also a constructive critic of the emerging industries manufacturing "soft technology" equipment like wind turbines.

In the 1990s, Baldwin wrote a book about Buckminster Fuller, his ideas, experiments, and influence, Bucky Works: Buckminster Fuller's Ideas for Today.

In the late 1990s, he worked with the Rocky Mountain Institute (Snowmass, Colorado) in the research, design, and development of the ultralight, ultra-efficient "Hypercar" — a prototype by way of which independent designers hope to show the way for the world's auto manufacturers. With conceptual development having begun in 1991, the current version of the Hypercar uses a small generator to power an electric motor in each wheel.

Given his long-term role as a "technology" editor, something should be mentioned about the scope of Baldwin's focus on technology. His interests remained broader than that represented in the shifting media and popular focus of the mid 1980s and later, which inclined to highlight the micro chip and electronic devices based on it. Baldwin has continued to point out the value of (and need for evaluation of) technologies within a larger perimeter. Certainly shelter and transportation technologies have always interested him. So have tools, and whether a device or tool or process was freshly innovative or age-old in concept, if it enabled a person to “do the job” with wood, metal, fiberglass panels, soil, trees, or whatever, it remained worthy of Baldwin’s attention. Whereas the personal computer often (though not necessarily) inclines its operator toward imagination, almost in the sense of entertainment, Baldwin has remained equally interested in doing, in application. And while he has never ceased to be interested in the products of the factory, Baldwin has always wanted to empower individuals and small teams of people to accomplish something.

Baldwin, as one of the notable designer technologists whose cross-disciplinary approaches have opened new territory, was featured in the 1994 documentary film Ecological Design: Inventing the Future. The film viewed these designers as "outlaws" whose careers have necessarily developed "outside the box" of their time, largely unsupported by mainstream industry and often beyond the pale of mainstream academia, as well.

J. Baldwin invented (and has built) a permanent, transparent, insulated structure — of aluminum and Teflon — he calls a "Pillow Dome," said to have withstood 135-mph winds and tons of snow. The Pillow Dome weighs just one-half pound per square foot. The basic approach has since been applied in large-scale applications such as the Eden Project in Cornwall, England. Baldwin continues to practice design (as exemplified in the unique and aerodynamic 'mobile-room' Quick-Up camper he has put on the market) and to teach design at the college level. In recent years, he has taught at Sonoma State University and at California College of Arts & Crafts.

Below is a list of some notable futurologists.

Robert Anton Wilson (born Robert Edward Wilson, January 18, 1932 – January 11, 2007), the American author of 35 influential books, became, at various times, a novelist, essayist, philosopher, futurist, polymath, psychonaut, libertarian[1] and self-described agnostic mystic. Recognized as an Episkopos, Pope, and Saint of Discordianism by Discordians who care to label him as such, Wilson helped publicize the group/religion/melee through his writings, interviews, and strolls.

Wilson described his work as an "attempt to break down conditioned associations, to look at the world in a new way, with many models recognized as models or maps, and no one model elevated to the truth." [2]

"My goal is to try to get people into a

state of generalized agnosticism, not agnosticism about God alone but

agnosticism about everything."[3]

| Stewart Brand | |

|---|---|

Brand speaking in 2004 |

|

| Born | December 14, 1938 Rockford, Illinois |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Writer, editor |

| Known for | The Whole Earth Catalog, The WELL, Long Now Foundation |

Stewart Brand (born December 14, 1938 in Rockford, Illinois) is an American writer, best known as editor of the Whole Earth Catalog. He founded a number of organizations including The WELL, the Global Business Network, and the Long Now Foundation. He is the author of several books, most recently Whole Earth Discipline.

Contents[hide] |

During Brand's childhood, his father worried that school was not stimulating Stewart to independent, creative thinking. His parents' response was to send him to Phillips Exeter Academy. After that he studied biology at Stanford University, graduating in 1960. As a soldier of the U.S. Army, he was a parachutist and taught infantry skills; he was later to express that his experience in the military fostered his competence in organizing. A civilian again, in 1962 he studied design at San Francisco Art Institute, photography at San Francisco State College, and participated in a legitimate scientific study of then-legal LSD, in Menlo Park, California.

Brand has lived in California ever since. Today, he and his wife, Ryan Phelan, live on Mirene, a 64-foot (20 m)-long working tugboat. Built in 1912, the boat is moored in a former shipyard in Sausalito, California.[1] He works in Mary Heartline, a fishing boat about 100 yards (91 m) away.[1] Otis Redding is said to have written “(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay” on a table Brand acquired from an antiques dealer in Sausalito.[1]

Through scholarship and by visiting numerous Indian reservations, he familiarized himself with the Native Americans of the West. Native Americans have continued to be an important cultural interest, an interest which has re-emerged in Brand's work in various ways through the years. He was married to Lois Jennings, an Ottawa Native American and mathematician.[2]

By the mid 1960s, he was associated with author Ken Kesey and the "Merry Pranksters," and in San Francisco, Brand produced the Trips Festival, an early effort involving rock music and light shows. About 10,000 hippies attended and Haight-Ashbury emerged as a community.[3] Tom Wolfe describes Brand in the beginning of his book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

In 1966, Brand campaigned to have NASA release the then-rumored satellite image of the entire Earth as seen from space. He distributed buttons—for 25 cents each[4]—asking, "Why haven't we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?"[5] He thought the image of our planet might be a powerful symbol. In 1968, a NASA astronaut made the photo[5] and in 1970 Earth Day began to be celebrated.[4] During a 2003 interview, Brand explained that the image "gave the sense that Earth’s an island, surrounded by a lot of inhospitable space. And it’s so graphic, this little blue, white, green and brown jewel-like icon amongst a quite featureless black vacuum." During this campaign Brand met Richard Buckminster Fuller, who offered to help him in his projects.

In late 1968, Brand assisted electrical engineer Douglas Engelbart with The Mother of All Demos, a famous presentation of many revolutionary computer technologies (including the mouse) to the Fall Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco.

Brand surmised that, given the necessary consciousness, information, and tools, human beings might reshape the world they had made (and were making) for themselves into something environmentally and socially sustainable. The fact that he had builders, designers, and engineers as friends surely influenced his reasoning.

During the late 1960s to early 1970s about 10 million Americans were involved in living communally.[6] In 1968, using the most basic of typesetting and page-layout tools, Brand and cohorts created issue number one of The Whole Earth Catalog.[7] Brand and his wife Lois travelled to communes in a 1963 Dodge truck that was the Whole Earth Truck Store which moved to a storefront in Menlo Park, California.[7] That first oversize Catalog, and its successors into the 1970s and later, reckoned that many sorts of things were useful "tools": books, maps, garden tools, specialized clothing, carpenters' and masons' tools, forestry gear, tents, welding equipment, professional journals, early synthesizers and personal computers, etc. Brand invited "reviews" of the best of these items from experts in specific fields, as though they were writing a letter to a friend. The information also made known where these things could be located or bought. The Catalog's publication coincided with the great wave of experimentalism, convention-breaking, and "do it yourself" attitude associated with the "counterculture".

The influence of these Whole Earth Catalogs on the rural back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s, and the communities movement within many cities, was widespread, being experienced in the U.S. and Canada and far beyond. A 1972 edition sold 1.5 million copies and in the U.S. won a National Book Award. Many people first learned about the potential of alternative energy production (e.g., solar, wind, small-hydro, geothermal) through the Catalog. (See also renewable energy.)

To continue this work and also to publish full-length articles on specific topics in natural sciences and invention, in numerous areas of arts and social sciences, and on the contemporary scene in general, Brand founded the CoEvolution Quarterly (CQ) during 1974, aimed primarily at educated laypersons. Brand never better revealed his opinions and reason for hope than when he ran, in CoEvolution Quarterly #4, a transcription of technology historian Lewis Mumford’s talk “The Next Transformation of Man,” containing the statement: "... man has still within him sufficient resources to alter the direction of modern civilization, for we then need no longer regard man as the passive victim of his own irreversible technological development."

Content of CQ often included futurism, or risqué topics. Besides giving space to unknown writers with something valuable to say, Brand presented articles by many respected authors and thinkers, including Lewis Mumford, Howard T. Odum, Witold Rybczynski, Karl Hess, Christopher Swan, Orville Schell, Ivan Illich, Wendell Berry, Ursula K. Le Guin, Gregory Bateson, Amory Lovins, Hazel Henderson, Gary Snyder, Lynn Margulis, Eric Drexler, Gerard K. O'Neill, Peter Calthorpe, Sim Van der Ryn, Paul Hawken, John Todd, J. Baldwin, Kevin Kelly (future editor of Wired magazine), and Donella Meadows. During ensuing years, Brand authored and edited a number of books on topics as diverse as computer-based media, the life-history of buildings, and ideas about space colonies.

During 1984 The Whole Earth Software Review (a supplement to The Whole Earth Software Catalog) was founded. It merged with CQ to form the Whole Earth Review in 1985.

During 1977-79, Brand served as "special advisor" in the administration of California Governor Jerry Brown.

During 1985, Brand and Larry Brilliant founded The WELL ("Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link"), a prototypic, broad-ranging online community for intelligent, informed participants the world over.The WELL won the 1990 Best Online Publication Award from the Computer Press Association.

During 1986, Brand was a visiting scientist at the Media Laboratory at MIT. Soon after, he became a private-conference organizer for such corporations as Royal Dutch/Shell, Volvo, and AT&T. During 1988, he became a co-founder of the Global Business Network, which explores global futures and business strategies informed by the sorts of values and information which Brand has always found vital. GBN has become involved with in the evolution and application of scenario thinking, planning, and complementary strategic tools. In other connections, Brand has been part of the board of the Santa Fe Institute (founded during 1984), an organization devoted to "fostering a multidisciplinary scientific research community pursuing frontier science." He has continued also to promote the preservation of tracts of wilderness.

The Whole Earth Catalog implied an ideal of human progress that depended on decentralized, personal, and liberating technological development — so called, "soft technology." However, during 2005 he criticized aspects of the international environmental ideology he helped develop. An article by him entitled Environmental Heresies, published in the May 2005 issue of the MIT Technology Review, describes what he considers necessary changes to environmentalism. In the article he suggested, among other things, that environmentalists embrace nuclear power and genetically modified organisms as technologies with more promise than risk. Relating specifically to atomic energy, Brand argued for a centralized global distributor of nuclear fuel without demonstrating any concern[neutrality disputed] for the possibility such an arrangement might become totalitarian. As these technologies are unavailable as tools to ordinary people but, rather, are wielded by a military, corporate, and academic techno-elite, some[who?] see Brand's recent statements as incompatible philosophically with his earlier work.

A few of Brand's aphorisms (on which he has elaborated) are: "Civilization’s shortening attention span is mismatched with the pace of environmental problems," "Environmental health requires peace, prosperity, and continuity," "Technology can be good for the environment," and (perhaps his most famous), [8] "Information wants to be free. Information also wants to be expensive. Information wants to be free because it has become so cheap to distribute, copy, and recombine — too cheap to meter. It wants to be expensive because it can be immeasurably valuable to the recipient. That tension will not go away. It leads to endless wrenching debate about price, copyright, 'intellectual property', the moral rightness of casual distribution, because each round of new devices makes the tension worse, not better." (Spoken at the first Hackers' Conference, and printed in the May 1985 Whole Earth Review. It later turned up in his book, The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT, published in 1987.) Whole Earth Catalog began with the words “We are as gods and we might as well get good at it.” and his book Whole Earth Discipline begins with "We are as gods and HAVE to get good at it." Brand wrote The WELL's sign on message, "You own your own words, unless they contain information. In which case they belong to no one."

Stewart Brand is the initiator or was involved with the development of the following:

| Nicholas Negroponte | |

|---|---|

Nicholas Negroponte delivering the Forrestal Lecture to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD on April 15, 2009 |

|

| Born | December 1, 1943 New York City,[unreliable source?] |

| Occupation | Academic and Computer Scientist |

| Spouse(s) | Elaine |

| Children | Dimitri Negroponte |

Nicholas Negroponte (born December 1, 1943) is a Greek-American architect and computer scientist best known as the founder and Chairman Emeritus of Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Media Lab, and also known as the founder of The One Laptop per Child association (OLPC).

Contents[hide] |

Negroponte was born to Dimitri John, a Greek shipping magnate, and grew up in New York City's Upper East Side. He is the younger brother of John Negroponte, former United States Deputy Secretary of State.

He attended many schools, including Buckley (NYC), Le Rosey (Switzerland) and Choate Rosemary Hall in Wallingford, Connecticut where he graduated in 1961. Subsequently, he studied at MIT as both an undergraduate and graduate student in Architecture where his research focused on issues of computer-aided design. He earned a Master's degree in architecture from MIT in 1966.

Negroponte joined the faculty of MIT in 1966. For several years thereafter he divided his teaching time between MIT and several visiting professorships at Yale, Michigan and the University of California, Berkeley.

In 1967, Negroponte founded MIT's Architecture Machine Group, a combination lab and think tank which studied new approaches to human-computer interaction. In 1985, Negroponte created the MIT Media Lab with Jerome B. Wiesner. As director, he developed the lab into the pre-eminent computer science laboratory for new media and a high-tech playground for investigating the human-computer interface.

In 1992, Negroponte became involved in the creation of Wired Magazine as the first investor. From 1993 to 1998, he contributed a monthly column to the magazine in which he reiterated a basic theme: "Move bits, not atoms."

Negroponte expanded many of the ideas from his Wired columns into a bestselling book Being Digital (1995), which made famous his forecasts on how the interactive world, the entertainment world and the information world would eventually merge. Being Digital was a bestseller and was translated into some twenty languages. Negroponte is a digital optimist who believed that computers would make life better for everyone[1] However, critics[who?] have faulted his techno-utopian ideas for failing to consider the historical, political and cultural realities with which new technologies should be viewed. Negroponte's belief that wired technologies such as telephones will ultimately become unwired by using airwaves instead of wires or fiber optics, and that unwired technologies such as televisions will become wired, is commonly referred to as the Negroponte switch.

In 2000, Negroponte stepped down as director of the Media Lab as Walter Bender took over as Executive Director. However, Negroponte retained the role of laboratory Chairman. When Frank Moss was appointed director of the lab in 2006, Negroponte stepped down as lab chairman to focus more fully on his work with One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) although he retains his appointment as professor at MIT.

In November 2005, at the World Summit on the Information Society held in Tunis, Negroponte unveiled a $100 laptop computer, The Children's Machine, designed for students in the developing world. The project is part of a broader program by One Laptop Per Child, a non-profit organisation started by Negroponte and other Media Lab faculty, to extend Internet access in developing countries.

Negroponte is an active angel investor and has invested in over 30 startup companies over the last 30 years, including Zagats, Wired, Ambient Devices, Skype and Velti. He sits on several boards, including Motorola (listed on the New York Stock Exchange) and Velti (listed on the London Stock Exchange). He is also on the advisory board of TTI/Vanguard. In August 2007, he was appointed to a five-member special committee with the objective of assuring the continued journalistic and editorial integrity and independence of the Wall Street Journal and other Dow Jones & Company publications and services. The committee was formed as part of the merger of Dow Jones with News Corporation.[2] Negroponte's fellow founding committee members are Louis Boccardi, Thomas Bray, Jack Fuller, and the late former Congresswoman Jennifer Dunn.

Magda Cordell McHale (née Lustigova) (born Hungary June 24, 1921, died Sloan (near Buffalo), New York February 21, 2008) was an artist, futurist, and educator. She was a founding member of the Independent Group which was a British movement that originated Pop Art which grew out of a fascination with American mass culture and post-WWII technologies. Later, she was a faculty member in the University at Buffalo School of Architecture & Planning. [1]

| “ | I was filled with pain and I hoped for a better world, | ” |

she recounted later. This expression of hope came to define her working practices for the rest of her life. “Society needs to know where it has been before it can know where it is going,” was her oft-cited mantra. [2]

Contents[hide] |

Born Magda Lustigova to a prominent family of grain merchants in Hungary, Magda fled to Egypt and then Palestine as a refugee during World War II to escape Nazi persecution. Here, she found work as a translator for British intelligence and met her first husband, Frank Cordell, who was also working for British intelligence. According to British architect Peter Smithson, Magda was “a force who had the capacity to turn her willpower to anything.” [2]

After the war, Lustigova and Cordell returned to London, where they established an artistic atelier at 52 Cleveland Square in Paddington London, which they shared and artistically collaborated with the British Modern artist John McHale. She and her husband rapidly became an integral part of the avant-garde artistic milieu that congregated around the Institute of Contemporary Arts. They were actively involved in the Independent Group (IG) (1952-56), a cross-cultural discussion group that included artists, writers, architects and critics who rejected the traditional dichotomies of high and low culture. The IG challenged the official Modernist assumptions of British aesthetics and pioneered a progressive, interdisciplinary, consumer-based aesthetic of inclusiveness. [2] The three artists collaborated on a variety of projects, and Magda McHale soon became indispensable to the activities of the IG for her writings as well as her archiving and organisation. She was closely involved with the exhibition This is Tomorrow at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1956, a multi-disciplinary show retrospectively credited with launching British Pop art.

The McHale/Cordell atelier occupied three floors in a large Georgian row house in Cleveland Square. Frank used the top floor with his piano and large windows overlooking the park as his music composing studio. John McHale occupied the large sky lit studio at the back of the atelier on the ground floor. Magda used the other large painting studio downstairs, which was also used by all three artist as a film studio. McHale used the downstairs film studio to produce his photograms for his Telemath collage series. There was also a separate downstairs workshop and photographic dark room. The living room on the ground floor was used for entertaining guests such as: Reyner Banham and other members of the ICA group, musicians, writers such as Eric Newby, dramatists such as Arnold Wesker, and international guests such as Buckminster Fuller, and Picasso's son, Paulo. Cordell made numerous tape recordings of Fuller.

Magda later recalled the significance of McHale’s return from his formative visit to America laden with imagery culled from American sources. “We all sat around on the floor for hours and looked through this unbelievable trunk of materials,” she said. [2]

In 1961, Magda divorced Cordell [3] and left for America with McHale, where they immersed themselves in academia. Encouraged by their dialogue with the American intellectual Buckminster Fuller, the McHales dedicated themselves to sociological research and published extensively on the impact of technology and culture, mass communications and the future. They moved from university to university propounding their ideas, teaching and publishing. During this time Magda published five books (three in collaboration with her husband) on future trends, and sat on numerous editorial boards. [2]

McHale’s self-expression characterised both her academic and artistic endeavours. Although the latter part of her life was publicly devoted to her research into sociology and “futurist” studies, she regarded herself as a painter first and foremost. She conveyed something of her drive when talking of her art practice: “I’m a binge painter. I can go on for days until I’m limp and all wrung out. I have tremendous amounts of energy.”

McHale's artistic works were characterised by expressive figuration and heavily influenced by the Art Brut of continental painters such as Jean Dubuffet and Wols. As a rare female voice at this time, McHale’s preoccupation with the female form explored existential questions. Her textured, impasto surfaces depict distorted forms that at once reflect the resilience of the human body and describe mid-20th-century anguish. McHale’s work was acknowledged in articles and exhibitions of the day; the influential critic Reyner Banham included an illustration of her work in his 1955 article "The New Brutalism", in The Architectural Review. McHale showcased her monotypes and collages in a 1955 exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) and her paintings at the Hanover Gallery in 1956, with later exhibitions at the University at Buffalo. [2]

Contemporary critics dwelt on the works’ sensuous, aggressive and primitivist qualities. “Her representation of women is not concerned with traditional notions of beauty or traditional cultural values . . . The result may be monstrous and uncompromising, but in this age of corsets, cosmetics, automation and celluloid sex, it might do us no harm to be shocked back into the realisation that there is still latent in the human being a savage instinct, fecundity and energy.” [2] Despite this new vista of art, she remained in her own work unswayed by the freedoms and allure of popular imagery and maintained her commitment to figuration. She later explained: “I am a European painter and for me that figure, that shape, is still superior to all that.” [2]

McHale's work is included in the collections of the Tate Modern in London and the Albright-Knox in Buffalo, New York.

John and Magda moved from the UK to Southern Illinois University where John managed the World Resources Inventory with Buckminister Fuller, then to SUNY Binghamton where John completed his PhD and, with Magda, started the Center for Integrative Studies. Later they moved to Texas where the center was operated under the aegis of University of Houston, V.P. Andrew Rudnick.

After the death of John McHale in 1978, Magda McHale was invited to Buffalo, New York, where she established and became director of the Centre for Integrative Studies at the State University of New York. The main focus of the centre was global trends, inter-generational shifts in thought and the impact of new technologies on contemporary culture.

Magda was on faculty in the Design Studies department in the School of Architecture & Planning at the University at Buffalo (also referred to as SUNY Buffalo). The department was dissolved by Dean Mike Brooks in the late 1980s, at which point, Magda moved to the Department of Planning (later the Department of Urban and Regional Planning). Her areas of scholarship included future studies; long-range consequences of social, cultural, and technological change on global societies.

In 2000 she endowed the McHale Fellowship at the University of Buffalo School of Architecture & Planning to support design work that speculates on the impact of new technologies. [2]

She was active in the World Academy of Art & Science and the World Futures Society. [4] She worked tirelessly as vice-president of the World Futures Federation and the World Academy of Art and Science. [3]

| James Ephraim Lovelock | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 26

July

1919

Letchworth, Hertfordshire, England |

| Residence | England |

| Nationality | British |

| Fields | Chemistry, Earth Science |

| Institutions | Independent researcher |

| Alma mater | University of Manchester London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine University of London Harvard Medical School |

| Known for | Electron capture detector Gaia hypothesis |

| Notable awards | FRS,

1974 Tswett Medal, 1975 ACS, 1980 WMO Norbert Gerbier Prize, 1988 Dr A.H. Heineken Prize for the Environment, 1990 CBE, 1990 CH, 2003 Arne Naess Chair in Global Justice and the Environment [1], 2007 |

James Ephraim Lovelock, CH, CBE, FRS (born 26 July 1919) is an independent scientist, author, researcher, environmentalist, and futurist who lives in Devon, England. He is known for proposing the Gaia hypothesis, in which he postulates that the Earth functions as a kind of superorganism.

Contents[hide] |

He was born in Letchworth Garden City in Hertfordshire, England, but moved to London where he was, by his own account, an unhappy pupil at Strand School.[1] He studied chemistry at the University of Manchester, before taking up a Medical Research Council post at the Institute for Medical Research in London.[2] His student status enabled temporary deferment of military service during the Second World War, but he registered as a conscientious objector.[3] He later abandoned this position in the light of Nazi atrocities and tried to enlist for war service, but was told that his medical research was too valuable for this to be considered.

In 1948 Lovelock received a Ph.D. degree in medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Within the United States he has conducted research at Yale, Baylor College of Medicine, and Harvard University.[2]

A lifelong inventor, Lovelock has created and developed many scientific instruments, some of which were designed for NASA in its programme of planetary exploration. It was while working as a consultant for NASA that Lovelock developed the Gaia Hypothesis, for which he is most widely known.

In early 1961, Lovelock was engaged by NASA to develop sensitive instruments for the analysis of extraterrestrial atmospheres and planetary surfaces. The Viking program, that visited Mars in the late 1970s, was motivated in part to determine whether Mars supported life, and many of the sensors and experiments that were ultimately deployed aimed to resolve this issue. During work on a precursor of this program, Lovelock became interested in the composition of the Martian atmosphere, reasoning that many life forms on Mars would be obliged to make use of it (and, thus, alter it). However, the atmosphere was found to be in a stable condition close to its chemical equilibrium, with very little oxygen, methane, or hydrogen, but with an overwhelming abundance of carbon dioxide. To Lovelock, the stark contrast between the Martian atmosphere and chemically-dynamic mixture of that of our Earth's biosphere was strongly indicative of the absence of life on the planet.[4] However, when they were finally launched to Mars, the Viking probes still searched (unsuccessfully) for extant life there.

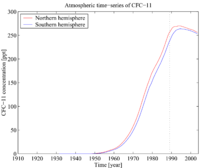

Lovelock invented the electron capture detector, which ultimately assisted in discoveries about the persistence of CFCs and their role in stratospheric ozone depletion.[5][6][7] After studying the operation of the Earth's sulfur cycle,[8] Lovelock and his colleagues developed the CLAW hypothesis as a possible example of biological control of the Earth's climate.[9]

Lovelock was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1974. He served as the president of the Marine Biological Association (MBA) from 1986 to 1990, and has been a Honorary Visiting Fellow of Green Templeton College, Oxford (formerly Green College, Oxford) since 1994. He has been awarded a number of prestigious prizes including the Tswett Medal (1975), an ACS chromatography award (1980), the WMO Norbert Gerbier Prize (1988), the Dr A.H. Heineken Prize for the Environment (1990) and the RGS Discovery Lifetime award (2001). He became a CBE in 1990, and a Companion of Honour in 2003.

An independent scientist, inventor, and author, Lovelock works out of a barn-turned-laboratory in Cornwall.

After the development of his electron capture detector, in the late 1960s, Lovelock was the first to detect the widespread presence of CFCs in the atmosphere.[5] He found a concentration of 60 parts per trillion of CFC-11 over Ireland and, in a partially self-funded research expedition in 1972, went on to measure the concentration of CFC-11 from the northern hemisphere to the Antarctic aboard the research vessel RRS Shackleton.[6][11] He found the gas in each of the 50 air samples that he collected but, not realising that the breakdown of CFCs in the stratosphere would release chlorine that posed a threat to the ozone layer, concluded that the level of CFCs constituted "no conceivable hazard".[11] He has since stated that he meant "no conceivable toxic hazard".

However, the experiment did provide the first useful data on the ubiquitous presence of CFCs in the atmosphere. The damage caused to the ozone layer by the photolysis of CFCs was later discovered by Frank Rowland and Mario Molina. After hearing a lecture on the subject of Lovelock's results,[12] they embarked on research that resulted in the first published paper that suggested a link between stratospheric CFCs and ozone depletion in 1974, and later shared the 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work.[13]

First formulated by Lovelock during the 1960s as a result of work for NASA concerned with detecting life on Mars,[14] the Gaia hypothesis proposes that living and non-living parts of the earth form a complex interacting system that can be thought of as a single organism.[15][16] Named after the Greek goddess Gaia at the suggestion of novelist William Golding,[11] the hypothesis postulates that the biosphere has a regulatory effect on the Earth's environment that acts to sustain life.

While the Gaia hypothesis was readily accepted by many in the environmentalist community, it has not been widely accepted within the scientific community. Among its more famous critics are the evolutionary biologists Richard Dawkins, Ford Doolittle, and Stephen Jay Gould — notable, given the diversity of this trio's views on other scientific matters. These (and other) critics have questioned how natural selection operating on individual organisms can lead to the evolution of planetary-scale homeostasis.[17]

Lovelock has responded to these criticisms with models such as Daisyworld, that illustrate how individual-level effects can translate to planetary homeostasis.

Lovelock has become concerned about the threat of global warming from the greenhouse effect. In 2004 he caused a media sensation when he broke with many fellow environmentalists by pronouncing that "only nuclear power can now halt global warming". In his view, nuclear energy is the only realistic alternative to fossil fuels that has the capacity to both fulfill the large scale energy needs of humankind while also reducing greenhouse emissions. He is an open member of Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy.

In 2005, against the backdrop of renewed UK government interest in nuclear power, Lovelock again publicly announced his support for nuclear energy, stating, "I am a Green, and I entreat my friends in the movement to drop their wrongheaded objection to nuclear energy".[18] Although these interventions in the public debate on nuclear power are recent, his views on it are longstanding. In his 1988 book The Ages of Gaia he states:

"I have never regarded nuclear radiation or nuclear power as anything other than a normal and inevitable part of the environment. Our prokaryotic forebears evolved on a planet-sized lump of fallout from a star-sized nuclear explosion, a supernova that synthesised the elements that go to make our planet and ourselves."[11]

In The Revenge of Gaia[19] (2006), where he puts forward the concept of sustainable retreat, Lovelock writes:

"A television interviewer once asked me, 'But what about nuclear waste? Will it not poison the whole biosphere and persist for millions of years?' I knew this to be a nightmare fantasy wholly without substance in the real world... One of the striking things about places heavily contaminated by radioactive nuclides is the richness of their wildlife. This is true of the land around Chernobyl, the bomb test sites of the Pacific, and areas near the United States' Savannah River nuclear weapons plant of the Second World War. Wild plants and animals do not perceive radiation as dangerous, and any slight reduction it may cause in their lifespans is far less a hazard than is the presence of people and their pets... I find it sad, but all too human, that there are vast bureaucracies concerned about nuclear waste, huge organisations devoted to decommissioning power stations, but nothing comparable to deal with that truly malign waste, carbon dioxide."

On 30 May 2006, Lovelock told the Australian Lateline television program: "Modern nuclear power stations are useless for making bombs".[20] This view may be based on the fact that plutonium-239 from the nuclear reactor of a power plant is contaminated with a significant amount of plutonium-240, complicating its use in nuclear weapons.[21] It is easier to enrich uranium than to separate 240Pu from 239Pu to produce weapons-grade material, although even reactor-grade plutonium can in fact be used in weapons, e.g. dirty bombs.[22][23] Friends of the Earth Australia responded: "Lovelock's claim that nuclear power plants cannot be used for weapons production is false, irresponsible and dangerous. A typical nuclear power reactor produces about 300 kilograms of plutonium each year, enough for 30 nuclear weapons".[20]

Writing in the British newspaper The Independent in January 2006, Lovelock argues that, as a result of global warming, "billions of us will die and the few breeding pairs of people that survive will be in the Arctic where the climate remains tolerable" by the end of the 21st century.[24] He has been quoted in The Guardian that 80% of humans will perish by 2100 AD, and this climate change will last 100,000 years.

He further predicts, the average temperature in temperate regions will increase by as much as 8°C and by up to 5°C in the tropics, leaving much of the world's land uninhabitable and unsuitable for farming, with northerly migrations and new cities created in the Arctic. He predicts much of Europe will become uninhabitable having turned to desert and Britain will become Europe's "life-raft" due to its stable temperature caused by being surrounded by the ocean. He suggests that "we have to keep in mind the awesome pace of change and realise how little time is left to act, and then each community and nation must find the best use of the resources they have to sustain civilisation for as long as they can".[24]

He partly retreated from this position in a September 2007 address to the World Nuclear Association's Annual Symposium, suggesting that climate change would stabilise and prove survivable, and that the Earth itself is in "no danger" because it would stabilise in a new state. Life, however, might be forced to migrate en masse to remain in habitable climes.[25] In 2008, he became a patron of the Optimum Population Trust, which campaigns for a gradual decline in the global human population to a sustainable level.[26]

In September 2007, Lovelock and Chris Rapley proposed the construction of ocean pumps comprising pipes "100 to 200 metres long, 10 metres in diameter and with a one-way flap valve at the lower end for pumping by wave movement" to pump water up from below the thermocline to "fertilize algae in the surface waters and encourage them to bloom".[27] The intention of this scheme is to accelerate the transfer of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to the ocean by increasing primary production and enhancing the export of organic carbon (as marine snow) to the deep ocean. At the time the authors noted that the idea "may fail, perhaps on engineering or economic grounds", and that "the impact on ocean acidification will need to be taken into account". However, a scheme similar to that proposed by Lovelock and Rapley is already being developed by a commercial company.[28]

The proposal attracted widespread media attention,[29][30][31][32] although also criticism.[33][34][35] Commenting on the proposal, Corinne Le Quéré, a University of East Anglia researcher, said "It doesn’t make sense. There is absolutely no evidence that geoengineering options work or even go in the right direction. I’m astonished that they published this. Before any geoengineering is put to work a massive amount of research is needed – research which will take 20 to 30 years".[29] Other researchers have claimed that "this scheme would bring water with high natural pCO2 levels (associated with the nutrients) back to the surface, potentially causing exhalation of CO2".[35]

| This article needs references that appear in reliable third-party publications. Primary sources or sources affiliated with the subject are generally not sufficient for a Wikipedia article. Please add more appropriate citations from reliable sources. (November 2008) |

| Jacque Fresco | |

|---|---|

Jacque Fresco (right) with Roxanne Meadows |

|

| Born | March 13, 1916 |

| Residence | Florida |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Futurist |

| Website http://www.thevenusproject.com/ |

|

Jacque Fresco is a self-educated industrial designer, author, lecturer, futurist, inventor, social engineer and the creator of The Venus Project.[1][2][3] Fresco has worked as both designer and inventor in a wide range of fields spanning biomedical innovations and integrated social systems. He believes his ideas would maximally benefit the greatest number of people and he states some of his influence stems from his formative years during the Great Depression.[4]

The Venus Project was started in the mid-1970s by Fresco and his partner, Roxanne Meadows. The film Future by Design was produced in 2006 describing his life and work. Fresco writes and lectures extensively on subjects ranging from the holistic design of sustainable cities, energy efficiency, natural resource management and advanced automation, focusing on the benefits it will bring to society.[2][5]

Contents[hide] |

Born on March 13, 1916, Jacque Fresco started his professional career as design consultant for Rotor Craft Helicopter Company. He served in the Army Design and Development Unit at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, U.S. and worked for the Raymond De-Icer Corporation based in Los Angeles, California, U.S., as a research engineer.[5][4]

He worked for many companies and in many fields such as technical consultant and technical advisor to the motion picture industry, industrial design instructor at the Art Center School in Hollywood, California. In Los Angeles, he was colleague and work associate of psychologist Donald Powell Wilson.[5][4]

In 1942, Fresco started the Revell Plastics Company (now Revell-Monogram) with Lou Glaser, working variously in aerospace research and development, architecture, efficient automobile design, bare-eye 3D cinematic projection methods and medical equipment design where he developed a three dimensional X-ray unit amongst other things.[5][4]

The Venus Project was started around 1975[2] by Fresco[1][6] and by former portrait artist, Roxanne Meadows[2] in Venus, Florida, USA. Its research center is a 21-acre (85,000 m2) property with various domed buildings of his design, where they work on books and films to demonstrate their concepts and ideas. Fresco has produced an extensive range of scale models based on his designs. [4] The Venus Project was incorporated in 1995.[7][8]

Venus project was founded on the idea that poverty is caused by the stifling of progress in technology, which itself is caused by the present world's profit-driven economic system.[9] The progression of technology, if it were carried on independent of its profitability, Fresco theorizes, would make more resources available to more people thereby reducing corruption and greed, and instead make people more likely to help each other.[10][6][11] Fresco advocates against a money-based economy in favor of what he refers to as a resource-based economy.[12]

In a 2008 interview with Fresco and Meadows, Fresco stated that a 'lack of credentials' has made it difficult for him to gain influence in academic circles.[2] He adds that when universities do invite him to speak, they often don't give him enough time to explain his views.[2]

The Venus Project is featured prominently in the 2008 documentary film Zeitgeist: Addendum, as a possible solution to the global problems explained in the first film and first half of the second film.[6] The film premiered at the 5th Annual Artivist Film Festival in Los Angeles, California on October 2, 2008, winning their highest award, and it was released online for free on Google video[13] on October 4, 2008.[14]. Following the movie The Zeitgeist Movement was established to aid the transition from a monetary based economy to a resource-based economy.

[dubious ]

A major theme of Fresco's is the concept of a resource-based economy that replaces the need for monetary economy we have now, which is "scarcity-oriented" or "scarcity-based". Fresco argues that the world is rich in natural resources and energy and that — with modern technology and judicious efficiency — the needs of the global population can be met with abundance, while at the same time removing the current limitations of what is deemed possible due to notions of economic viability.

He gives this example to help explain the idea:

Fresco states that for this to work, all of the Earth's resources must be held as the common heritage of all people and not just a select few; and the practice of rationing resources through monetary methods is irrelevant and counter-productive to the survival of human civilization.[16]

One of the key points in Fresco’s solution is that without the

conditions created in a monetary system, vast amounts of resources

would not be wasted unproductively. Instead Fresco’s contention is that

without the waste of resources on ends that would become irrelevant

there would be no scarcity of necessary products such as food and

education.

| This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (July 2008) |

Jamais Cascio is a San Francisco Bay Area-based writer and ethical futurist.

In the 1990s, Cascio worked for the futurist and scenario planning firm Global Business Network. In 2003, he co-founded the popular environmental website Worldchanging, where he was a primary contributor.

At Worldchanging, he covered a broad variety of topics, from energy and climate change to global development, open source, and bio- and nanotechnologies. In early 2006, he left Worldchanging, and now blogs at Open The Future, a title based on his WorldChanging.com essay, 'The Open Future'.

He currently serves as the Global Futures Strategist for the Center for Responsible Nanotechnology, is a Fellow at the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, and is a Research Affiliate at the Institute for the Future.

Cascio is also known as a speculative futurist, having written two books for the GURPS science fiction role-playing game series "Transhuman Space", Broken Dreams (2002) and Toxic Memes (2003).

Cascio's work could be classified as techno-progressive. He speaks and writes frequently on the use of future studies as a tool for anticipating and managing environmental and technological crises. In 2006, he spoke at the TED conference. In 2009, Cascio was named by Foreign Policy Magazine as #72 among their "Top 100 Global Thinkers".

Gaston Berger (1 October 1896 – 13 November 1960) was a French futurist but also an industrialist, a philosopher and a state manager. He is mainly known for his remarkably lucid analysis of Edmund Husserl's Phenomenology and for his studies on the character structure.

Berger was born in Saint-Louis, Senegal. After managing a fertilizer plant during the 1930s, he created in Paris the Centre Universitaire International et des Centres de Prospective and directed the philosophical studies (Études philosophiques). The term prospective, invented by Gaston Berger, is the study of the possible futures.

From 1953 to 1960 he was in charge of the tertiary education at the Minister of National Education and modernised the French universities system. He was elected at the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques in 1955.

In 1957 he founded the journal Prospective and the homonym centre with André Gros. This same year he created the Institut national des sciences appliquées (INSA) of Lyon with the rector Capelle.

He was the father of the French choreographer Maurice Béjart (1927-2007). The

university of Saint-Louis, Senegal, where he was born is named after

him.

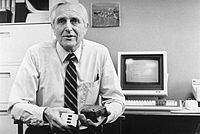

| Dr. Douglas C. Engelbart | |

|---|---|

Douglas Engelbart in 1984, showing two mice

|

|

| Born | January

30,

1925

Portland, Oregon, USA |

| Citizenship | US |

| Nationality | US |

| Ethnicity | German (father's side), Norwegian and Swedish (mother's side) |

| Fields | Inventor |

| Institutions | SRI, Xerox PARC, Doug Engelbart Institute |

| Alma mater | Oregon State College (BS); UC Berkeley (PhD) |

| Doctoral advisor | John R. Woodyard |

| Known for | Computer mouse, Hypertext, Groupware, Interactive Computing |

| Notable awards | National Medal of Technology, Lemelson-MIT Prize, Turing Award, Lovelace Medal, Norbert Wiener Award for Social and Professional Responsibility, Fellow Award, Computer History Museum |

Dr. Douglas C. Engelbart (born January 30, 1925) is an American inventor and early computer pioneer. He is best known for inventing the computer mouse,[1] as a pioneer of human-computer interaction whose team developed hypertext, networked computers, and precursors to GUIs; and as a committed and vocal proponent of the development and use of computers and networks to help cope with the world’s increasingly urgent and complex problems.[2]

His lab at SRI was responsible for more breakthrough innovation than possibly any other lab before or since. Engelbart had embedded in his lab a set of organizing principles, which he termed his "bootstrapping strategy", which he specifically designed to bootstrap and accelerate the rate of innovation achievable.[3]

Contents[hide] |

Engelbart was born in the U.S. state of Oregon on January 30, 1925 to Carl Louis Engelbart and Gladys Charlotte Amelia Munson Engelbart. He is of German, Swedish and Norwegian descent.[4]

He was the middle of three children, with a sister Dorianne (3 years older), and a brother David (14 months younger). They lived in Portland in his early years, and moved to the countryside to a place called Johnson Creek when he was 9 or 10, after the death of his father. He graduated from Portland's Franklin High School in 1942.