Individualist

anarchism

From Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

Individualist anarchism refers to

several traditions of thought within the anarchist movement that emphasize the individual

and his/her will

over any kinds of external determinants such as groups, society,

traditions, and ideological systems.[1][2]

Individualist anarchism is not a single philosophy but refers to a

group of individualistic philosophies that sometimes are in conflict.

Early influences in individualist anarchism were the thought of William Godwin[3],

Henry David Thoreau (transcendentalism)[4],

Josiah Warren ("sovereignty

of the individual"), Lysander Spooner ("natural

law"), Pierre Joseph

Proudhon (mutualism), Herbert Spencer ("law of equal liberty")[5]

and Max Stirner (egoism).[6]

From there it expanded through Europe

and the United States.

Benjamin R. Tucker,

a famous 19th century individualist anarchist, held that "if the

individual has the right to govern himself, all external government is

tyranny."[7]

Overview

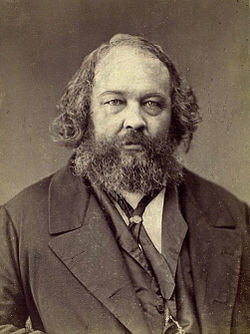

Early individualist anarchists include William Godwin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Max

Stirner.[3][6]

Individualist anarchism of different

kinds have a few things in common. These are:

1. The concentration and elevation on

the individual and his/her

over any kind of social or exterior reality or construction such as

morality, ideology, social custom, religion, metaphysics, ideas or the

will of others.[8][9]

2. The rejection or reservations on the

idea of revolution seeing it as a time of mass uprising

which could bring about new hierarchies. Instead they favor more evolutionary methods of bringing about anarchy

through alternative experiences and experiments and education which

could be brought about today[10][11].

This

also because it is not seen desirable for individuals the fact of

having to wait for revolution to start experiencing alternative

experiences outside what is offered in the current social system[12].

3. The view that relationships with

other persons or things can only

be of one's own interest and can be as transitory and without

compromises as desired since in individualist anarchism sacrifice is

usually rejected. In this way Max Stirner recommended associations of

egoists[13][14].

Individual experience and exploration therefore is emphazised.

As such differences exist. In regards to

economic questions there are adherents to mutualism (Proudhon, Emile Armand, early Benjamin Tucker), egoistic disrespect for "ghosts" such as

private property and markets (Stirner, John Henry Mackay, Lev

Chernyi, later Tucker), and adherents to anarcho-communism (Albert Libertad, illegalism).

The egoist form of individualist anarchism,

derived from the philosophy of Max Stirner,

supports the individual doing exactly what he pleases – taking no

notice of God, state, or moral rules.[15]

To Stirner, rights were spooks

in the mind, and he held that society does not exist but "the

individuals are its reality"– he supported property by force of might

rather than moral right.[16]

Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw "associations of egoists"

drawn together by respect for each other's ruthlessness.[17]

An important tendency within

individualist anarchist currents

emphasizes individual subjective exploration and defiance of social

conventions. As such Murray Bookchin

describes a lot of individualist anarchism as people who "expressed

their opposition in uniquely personal forms, especially in fiery

tracts, outrageous behavior, and aberrant lifestyles in the cultural

ghettos of fin de sicle New York, Paris, and London. As a credo,

individualist anarchism remained largely a bohemian

lifestyle, most conspicuous in its demands for sexual freedom ('free

love') and enamored of innovations in art, behavior, and clothing."[18].

In this way free love[19][20]

currents and other radical lifestyles such as naturism[20][21]

had popularity among individualist anarchists.

People

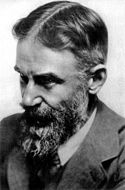

William Godwin

Main

article:

William GodwinWilliam Godwin can be considered an

individualist anarchist[22]

and philosophical

anarchist who was influenced by the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment,[23]

and developed what many consider the first expression of modern anarchist thought.[3]

Godwin was, according to Peter Kropotkin,

"the first to formulate the political and economical conceptions of

anarchism, even though he did not give that name to the ideas developed

in his work."[24][25]

Godwin advocated extreme individualism, proposing that all cooperation

in labor be eliminated.[26]

Godwin was a utilitarian who believed that all individuals are not of

equal value, with some of us "of more worth and importance' than others

depending on our utility in bringing about social good. Therefore he

does not believe in equal rights, but the person's life that should be

favored that is most conducive to the general good.[27]

Godwin opposed government because it infringes on the individual's

right to "private judgement" to determine which actions most maximize

utility, but also makes a critique of all authority over the

individual's judgement. This aspect of Godwin's philosophy, minus the

utilitarianism, was developed into a more extreme form later by Stirner.[28]

Godwin's individualism was to such a

radical degree that he even

opposed individuals performing together in orchestras, writing in Political Justice that "everything

understood by the term co-operation is in some sense an evil."[26]

The only apparent exception to this opposition to cooperation is the

spontaneous association that may arise when a society is threatened by

violent force. One reason he opposed cooperation is he believed it to

interfere with an individual's ability to be benevolent for the greater

good. Godwin opposes the idea of government, but wrote that a minimal state as a present "necessary

evil"[29]

that would become increasingly irrelevant and powerless by the gradual

spread of knowledge.[3]

He expressly opposed democracy, fearing oppression of the individual

by the majority (though he believed it to be preferable to dictatorship).

Godwin supported individual ownership of

property, defining it as

"the empire to which every man is entitled over the produce of his own

industry."[29]

However, he also advocated that individuals give to each other their

surplus property on the occasion that others have a need for it,

without involving trade (e.g. gift

economy). Thus, while people have the right to private

property, they should give it away as enlightened altruists. This was to be based on utilitarian

principles; he said: "Every man has a right to that, the exclusive

possession of which being awarded to him, a greater sum of benefit or

pleasure will result than could have arisen from its being otherwise

appropriated."[29]

However, benevolence was not to be enforced, being a matter of free

individual "private judgement." He did not advocate a community of

goods or assert collective ownership as is embraced in communism,

but his belief that individuals ought to share with those in need was

influential on the later development of anarchist communism.

Godwin's political views were diverse

and do not perfectly agree

with any of the ideologies that claim his influence; writers of the Socialist Standard, organ of the Socialist Party of Great

Britain, consider Godwin both an individualist and a communist;[30]

anarcho-capitalist Murray Rothbard did not regard Godwin as

being in the individualist camp at all, referring to him as the

"founder of communist anarchism";[31]

and historian Albert Weisbord considers him an

individualist anarchist without reservation.[32]

Some writers see a conflict between Godwin's advocacy of "private

judgement" and utilitarianism, as he says that ethics requires that

individuals give their surplus property to each other resulting in an

egalitarian society, but, at the same time, he insists that all things

be left to individual choice.[3]

Many of Godwin's views changed over time, as noted by Kropotkin.

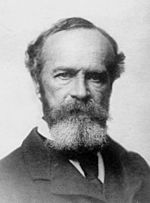

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865) was

the first philosopher to label himself an "anarchist."[33]

Some consider Proudhon to be an individualist anarchist,[34][35][36]

while others regard him to be a social anarchist.[37][38]

Some commentators do not identify Proudhon as an individualist

anarchist due to his preference for association in large industries,

rather than individual control.[39]

Nevertheless, he was influential among some of the American

individualists; in the 1840s and 1850s, Charles A. Dana,[40]

and William B. Greene

introduced Proudhon's works to the United

States. Greene adapted Proudhon's mutualism to American conditions

and introduced it to Benjamin R. Tucker.[41]

Proudhon opposed government privilege

that protects capitalist,

banking and land interests, and the accumulation or acquisition of

property (and any form of coercion

that led to it) which he believed hampers competition and keeps wealth

in the hands of the few. Proudhon favoured a right of individuals to

retain the product of their labor as their own property, but believed

that any property beyond that which an individual produced and could

possess was illegitimate. Thus, he saw private property as both

essential to liberty and a road to tyranny, the former when it resulted

from labor and was required for labor and the latter when it resulted

in exploitation (profit, interest, rent, tax). He generally called the

former "possession" and the latter "property." For large-scale

industry, he supported workers associations to replace wage labour and

opposed the ownership of land.

Proudhon maintained that those who labor

should retain the entirety of what they produce, and that monopolies

on credit and land are the forces that prohibit such. He advocated an

economic system that included private property as possession and

exchange market but without profit, which he called mutualism. It is Proudhon's

philosophy that was explicitly rejected by Joseph Dejacque in the

inception of anarchist-communism,

with

the latter asserting directly to Proudhon in a letter that "it is

not the product of his or her labor that the worker has a right to, but

to the satisfaction of his or her needs, whatever may be their nature."

An individualist rather than anarchist communist,[34][35][36]

Proudhon said that "communism...is the very denial of society in its

foundation..."[42]

and famously declared that "property is theft!"

in reference to his rejection of ownership rights to land being granted

to a person who is not using that land.

After Dejacque and others split from

Proudhon due to the latter's

support of individual property and an exchange economy, the

relationship between the individualists, who continued in relative

alignment with the philosophy of Proudhon, and the anarcho-communists

was characterised by various degrees of antagonism and harmony. For

example, individualists like Tucker on the one hand translated and

reprinted the works of collectivists like Mikhail Bakunin, while on the other hand

rejected the economic aspects of collectivism and communism as

incompatible with anarchist ideals.

Thought

Mutualism

Modern symbol of mutualism

Mutualism is an anarchist

school of thought which can be traced to the writings of

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who envisioned a society where each person

might possess a means of production, either

individually or collectively, with trade representing equivalent

amounts of labor in the free

market.[43]

Integral to the scheme was the establishment of a mutual-credit bank

which would lend to producers at a minimal interest rate only high

enough to cover the costs of administration.[44]

Mutualism is based on a labor theory of value

which holds that when labor or its product is sold, in exchange, it

ought to receive goods or services embodying "the amount of labor

necessary to produce an article of exactly similar and equal utility".[45]

Some mutualists believe that if the state did not intervene, as a

result of increased competition in the marketplace, individuals would

receive no more income than that in proportion to the amount of labor

they exert.[46]

Mutualists oppose the idea of individuals receiving an income through

loans, investments, and rent, as they believe these individuals are not

laboring. Some of them argue that if state intervention ceased, these

types of incomes would disappear due to increased competition in

capital.[47]

Though Proudhon opposed this type of income, he expressed: "... I never

meant to ... forbid or suppress, by sovereign decree, ground rent and

interest on capital. I believe that all these forms of human activity

should remain free and optional for all."[48]

Insofar as they ensure the workers right

to the full product of their labor, mutualists support markets

and private property

in the product of labor. However, they argue for conditional titles to

land, whose private ownership is legitimate only so long as it remains

in use or occupation (which Proudhon called "possession.")[49]

Proudhon's Mutualism supports labor-owned cooperative firms and

associations[50]

for "we need not hesitate, for we have no choice. . . it is necessary

to form an ASSOCIATION among workers . . . because without that, they

would remain related as subordinates and superiors, and there would

ensue two . . . castes of masters and wage-workers, which is repugnant

to a free and democratic society" and so "it becomes necessary for the

workers to form themselves into democratic

societies, with equal conditions for all

members, on pain of a relapse into feudalism."[51]

As for capital goods (man-made, non-land, "means of production"), mutualist

opinions differs on whether these should be commonly managed public

assets or private property.

Mutualists, following Proudhon,

originally considered themselves to

be libertarian socialists. However, "some mutualists have abandoned the

labor theory of value, and prefer to avoid the term "socialist." But

they still retain some cultural attitudes, for the most part, that set

them off from the libertarian right."[52]

Mutualists have distinguished themselves from state socialism,

and don't advocate social control over the means of production.

Benjamin Tucker said of Proudhon, that "though opposed to socializing

the ownership of capital, [Proudhon] aimed nevertheless to socialize

its effects by making its use beneficial to all instead of a means of

impoverishing the many to enrich the few...by subjecting capital to the

natural law of competition, thus bringing the price of its own use down

to cost."[53]

Egoism

Max

Stirner's philosophy, sometimes called "egoism," is the most extreme[54]

form of individualist anarchism. Max

Stirner was a Hegelian

philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in

historically-orientated surveys of anarchist thought as one of the

earliest and best-known exponents of individualist anarchism."[6]

In 1844, his The Ego and Its Own (Der

Einzige and sein Eigentum which may literally be translated as The

Unique Individual and His Property[55])

was published, which is considered to be "a founding text in the

tradition of individualist anarchism."[6]

Stirner does not recommend that the individual try to eliminate the

state but simply that they disregard the state when it conflicts with

one's autonomous choices and go along with it when doing so is

conducive to one's interests.[56]

He says that the egoist rejects pursuit of devotion to "a great idea, a

good cause, a doctirine, a system, a lofty calling," saying that the

egoist has no political calling but rather "lives themselves out"

without regard to "how well or ill humanity may fare thereby."[57]

Stirner held that the only limitation on the rights of the individual

is his power to obtain what he desires.[58]

He proposes that most commonly accepted social institutions—including

the notion of State, property as a right, natural rights in general,

and the very notion of society—were mere spooks in the mind.

Stirner wants to "abolish not only the state but also society as an

institution responsible for its members."[59]

He advocated self-assertion and foresaw "associations of egoists" where

respect for ruthlessness drew people together.[22]

Even murder is permissible "if it is right for me."[60]

For Stirner, property simply comes about

through might: "Whoever

knows how to take, to defend, the thing, to him belongs property." And,

"What I have in my power, that is my own. So long as I assert myself as

holder, I am the proprietor of the thing." He says, "I do not step

shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property,

in which I respect nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my

property!".[61]

His concept of "egoistic property" not only a lack of moral restraint

on how own obtains and uses things, but includes other people

as well.[62]

His embrace of egoism is in stark contrast to Godwin's altruism.

Stirner was opposed to communism, seeing it as a form of authority over

the individual.

This position on property is much

different from the native

American, natural law, form of individualist anarchism, which defends

the inviolability of the private property that has been earned through

labor[63]

and trade. However, in 1886 Benjamin Tucker rejected the natural rights

philosophy and adopted Stirner's egoism, with several others joining

with him. This split the American individualists into fierce debate,

"with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying

libertarianism itself."[64]

Other egoists include James L. Walker, Sidney Parker, Dora

Marsden, John Beverly Robinson,

and Benjamin Tucker (later in life).

In Russia, individualist anarchism

inspired by Stirner combined with an appreciation for Friedrich Nietzsche attracted a small

following of bohemian artists and intellectuals such as Lev

Chernyi, as well as a few lone wolves who found self-expression in

crime and violence.[65]

They rejected organizing, believing that only unorganized individuals

were safe from coercion and domination, believing this kept them true

to the ideals of anarchism.[66]

This type of individualist anarchism inspired anarcho-feminist Emma

Goldman[65]

Though Stirner's philosophy is

individualist, it has influenced some

libertarian communists and anarcho-communists. "For Ourselves Council

for Generalized Self-Management" discusses Stirner and speaks of a

"communist egoism," which is said to be a "synthesis of individualism

and collectivism," and says that "greed in its fullest sense is the

only possible basis of communist society."[67]

Forms of libertarian communism such as Situationism

are influenced by Stirner.[68]

Anarcho-communist Emma Goldman was influenced by both Stirner

and Peter Kropotkin and blended their

philosophies together in her own, as shown in books of hers such as Anarchism

And Other Essays.[69]

Free Love

An important current within

individualist anarchism is Free

love[19].

Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah

Warren

and to experimental communities, viewed sexual freedom as a clear,

direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love

particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws

discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth

control measures[19].

The most important American free love journal was Lucifer the Lightbearer

(1883-1907) edited by Moses

Harman and Lois Waisbrooker[70]

but also there existed Ezra

Heywood and Angela Heywood's The Word (1872-1890, 1892-1893)[19].

Also M. E. Lazarus was an important american

individualist anarchist who promoted free love[19].

In Europe the main propagandist of free love within individualist

anarchism was Emile Armand[71].

He proposed the concept of la camaraderie amoureuse

to speak of free love as the possibility of voluntary sexual encounter

between consenting adults. He was also a consistent proponent of polyamory[71].

The brazilian

individualist

anarchist Maria Lacerda de Moura lectured on

topics such as education, women's rights, free

love, and antimilitarism. Her writings and essays

landed her attention not only in Brazil, but also in Argentina

and Uruguay.

[72].

Anarcho-naturism

Another important current especially

within French and Spanish individualist anarchist groups was naturism[20].

Naturism promoted an ecological worldview, small ecovillages,

and most prominently nudism as a way to avoid the

artificiality of the industrial mass

society of modernity[21].

Naturist

individualist anarchists saw the individual in his biological,

physical and psychological aspects and avoided and tried to eliminate

social determinations [21].

An early influence in this vein was Henry David Thoreau and his famous

book Walden[20].

Important promoters of this were Henri

Zisly and Emile Gravelle who collaborated in La

Nouvelle Humanité followed by Le Naturien, Le

Sauvage, L'Ordre Naturel, & La Vie Naturelle [73]

Their ideas were important in individualist anarchist circles in France

but also in Spain where Federico Urales (pseudonym

of Joan Montseny), promotes the ideas of Gravelle and Zisly in La Revista Blanca (1898 – 1905)[20].

Anglo

American individualist anarchism

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) was an

important early influence in individualist anarchist thought in the

United States and Europe[11].

Thoreau was an American author, poet, naturalist, tax resiste, development critic , surveyor,

historian, philosopher, and leading transcendentalist.

He is best known for his book Walden,

a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and

his essay, Civil Disobedience,

an

argument for individual resistance to civil government in moral

opposition to an unjust state. His thought is an early influence on

green anarchism but with an emphasis on the individual experience of

the natural world influencing later naturist currents,[4]Simple

living as a rejection of a materialist lifestyle[4]

and self-sufficiency were Thoreau's goals,

and the whole project was inspired by transcendentalist philosophy.

The American version of individualist

anarchism has a strong emphasis on the non-aggression principle and individual sovereignty.[74]

Some individualist anarchists, such as Thoreau[75][76],

do

not speak of economics but simply the right of "disunion" from the

state, and foresee the gradual elimination of the state through social

evolution. His anarchism not only rejects the state but all organized

associations of any kind, advocating complete individual self reliance.[77]

An early individualist anarchist who was

very influential was Josiah

Warren, who had participated in a failed collective "utopian

socialist" experiment headed by Robert

Owen called "New Harmony" and came to the conclusion that

such a system is inferior to one that respects the "sovereignty[78]

of the individual" and his right to dispose of his property as his own

self-interest prescribes.

The "Boston

Anarchists"

Another form of individualist anarchism

was found in the United States, as advocated by the "Boston anarchists."[65]

By default American individualists didn't have any problem that "one

man employ another" or that "he direct him," in his labor but demanded

that "all natural opportunities requisite to the production of wealth

be accessible to all on equal terms and that monopolies arising from

special privileges created by law be abolished."[79]

They believed state monopoly capitalism

(defined as a state-sponsored monopoly)[80]

prevented labor from being fully rewarded. Voltairine de Cleyre,

summed up the philosophy by saying that the anarchist individualists

"are firm in the idea that the system of employer and employed, buying

and selling, banking, and all the other essential institutions of

Commercialism, centered upon private property, are in themselves good,

and are rendered vicious merely by the interference of the State."[81]

Even among the nineteenth century

American individualists, there was

not a monolithic doctrine, as they disagreed amongst each other on

various issues including intellectual property rights and possession versus property

in land.[82][83][84]

A major schism occurred later in the 19th century when Tucker and some

others abandoned their traditional support of natural rights -as espoused by Lysander Spooner- and converted to an

"egoism" modeled upon Stirner's philosophy.[83]

Some "Boston anarchists", including

Benjamin Tucker, identified themselves as "socialists"

which in the 19th century was often used in the broad sense of a

commitment to improving conditions of the working class (i.e. "the labor problem").[85]

By the turn of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism

had passed,[86]

although the individualist anarchist tradition was later revived with

modifications by Murray Rothbard and his anarcho-capitalism in the mid-twentieth

century, as a current of the broader libertarian movement.[65][87]

Anarcho-capitalism

19th century individualist anarchists

espoused the labor theory of value.

Some believe that the modern movement of anarcho-capitalism is the

result of simply removing the labor theory of value from ideas of the

19th century American individualist anarchists: "Their successors

today, such as Murray Rothbard, having abandoned the labor theory of

value, describe themselves as anarcho-capitalists."[88]

As economic theory changed, the popularity of the labor theory of classical economics was superseded by

the subjective theory of value of neo-classical

economics. According to Kevin

Carson (himself a mutualist), "most people who

call themselves "individualist anarchists" today are followers of

Murray Rothbard's Austrian economics."[89]

Murray Rothbard, a student of Ludwig von Mises, combined the Austrian school

economics of his teacher with the absolutist views of human rights and

rejection of the state he had absorbed from studying the individualist

American anarchists of the nineteenth century such as Lysander Spooner

and Benjamin Tucker.[90]

In the mid-1950s Rothbard wrote an

article under a pseudonym, saying

that "we are not anarchists...but not archists either...Perhaps, then,

we could call ourselves by a new name: nonarchist," concerned with

differentiating himself from communist and socialistic economic views

of other anarchists (including the individualist anarchists of the

nineteenth century).[91]

However, Rothbard later chose the term "anarcho-capitalism" for his

philosophy and referred to himself as an anarchist.

Agorism

Agorism is a radical left-libertarian[δ]

form of anarchism, developed from anarcho-capitalism in the late

20th-century by Samuel Edward Konkin III (a.k.a.

SEK3). The goal of agorists is a society in which all "relations

between people are voluntary exchanges – a free

market."[92]

Agorists are propertarian market anarchists who

consider that property rights are natural rights

deriving from the primary right of self-ownership and are not opposed

in principle to collectively held property if individual owners of the

property consent to collective ownership by contract or other voluntary

mutual agreement. However, Agorists are divided on the question of intellectual property rights.[δ]

European

individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism was one of the

three categories of anarchism in Russia, along with the

more prominent anarchist communism and anarcho-syndicalism.[93]

The ranks of the Russian individualist anarchists were predominantly

drawn from the intelligentsia and the working

class.[93]

European individualist anarchists

include Max Stirner, Albert Libertad, Shmuel Alexandrov, Anselme Bellegarrigue, Émile Armand, Enrico Arrigoni, Lev

Chernyi, John Henry Mackay, Han

Ryner, Renzo Novatore, Miguel Giménez Igualada,

and currently Michel Onfray. Two influential authors in

European individualist anarchists are Friedrich Nietzche

(see Anarchism and Friedrich

Nietzsche) and Georges Palante.

European individualist anarchism

proceeded from the roots laid by William Godwin, Pierre Joseph

Proudhon and Max Stirner.

France

From the legacy of Proudhon and Stirner

there emerged a strong

tradition of French individualist anarchism. An early important

individualist anarchist was Anselme Bellegarrigue. He

participated in the French Revolution of 1848,

was author and editor of 'Anarchie, Journal de l'Ordre and Au

fait ! Au

fait ! Interprétation de l'idée démocratique'

and wrote the important

early Anarchist Manifesto in 1850.

Later this tradition continued with such

intellectuals as Albert Libertad, André

Lorulot, Emile Armand, Victor

Serge, Zo d'Axa and Rirette Maitrejean developed theory in

the main individualist anarchist journal in France, L’Anarchie in 1905. Outside this journal, Han

Ryner wrote Petit Manuel individualiste (1903). Later

appeared the journal L'EnDehors

created by Zo d'Axa in 1891.

French individualist anarchist exposed a

diversity of positions (per

example, about violence and non-violence). For example Emile Armand

rejected violence and embraced mutualism while becoming an

important propagandist for free

love, while Albert Libertad and Zo d’Axa was influential in violentists

circles and championed violent propaganda by the

deed while adhering to communitarianism or anarcho-communism [94]

and rejecting work. Han Ryner on the other

side conciled anarchism with stoicism.

Nevertheless French individualist circles had a strong sense of

personal libertarianism and experimentation. Naturism

and free

love

contents started to have a strong influence in individualist anarchist

circles and from there it expanded to the rest of anarchism also

appearing in Spanish individualist anarchist groups[20].

"In this sense, the theoretical

positions and the vital experiences

of french individualism are deeply iconoclastic and scandalous, even

within libertarian circles. The call of nudist naturism,

the

strong defence of bith control methods, the idea of "unions of

egoists" with the sole justification of sexual practices, that will try

to put in practice, not without difficulties, will establish a way of

thought and action, and will result in symphathy within some, and a

strong rejection within others."[20]

Illegalism

Illegalism[95]

is an anarchist philosophy that developed primarily in France, Italy,

Belgium, and Switzerland during the early 1900s as an outgrowth of

Stirner's individualist anarchism[96].

Illegalists

usually did not seek moral basis for their actions,

recognizing only the reality of "might" rather than "right"; for the

most part, illegal acts were done simply to satisfy personal desires,

not for some greater ideal[97],

although some committed crimes as a form of Propaganda of the deed [95].

The illegalists embraced direct

action and propaganda by the

deed[98].

Influenced by theorist Max Stirner's egoism as well as Proudhon (his view that Property is theft!), Clément Duval and Marius

Jacob proposed the theory of la reprise individuelle (Eng: individual reclamation) which

justified robbery on the rich and personal direct action against

exploiters and the system.[97],

Illegalism first rose to prominence

among a generation of Europeans inspired by the unrest of the 1890s,

during which Ravachol, Émile Henry, Auguste Vaillant, and Caserio committed daring crimes in

the name of anarchism[99],

in what is known as propaganda of the deed. France's Bonnot

Gang was the most famous group to embrace illegalism.

Italy

In Italy individualist anarchism had a

strong tendency towards illegalism

and violent propaganda by the

deed similar to French individualist anarchism but perhaps more

extreme[100].

In this respect we can consider notorious magnicides carried out or

attempted by individualists Giovanni Passannante, Sante Caserio, Michele Angiolillo, Luigi Luccheni, Gaetano Bresci who murdered king Umberto I. Caserio lived in France and

coexisted within French illegalism and later assassinated French

president Sadi Carnot. The theoretical seeds of current Insurrectionary anarchism

were already laid out at the end of 19th century Italy in a combination

of individualist anarchism criticism of permanent groups and

organization with a socialist class struggle worldview[101].During

the rise of fascism this thought also motivated Gino

Lucetti, Michele Schirru and Angelo Sbardellotto in attempting the

assassination of Benito Mussolini.

During the early 20th century it is

important the intellectual work of individualist anarchist Renzo Novatore which was influenced by

Stirner, Friedrich Nietzsche, Georges Palante, Oscar

Wilde, Henrik Ibsen, Arthur Schopenhauer and Charles Baudelaire. He collaborated in

numerous anarchist journals and participated in futurism

avant-garde currents. In his thought he adhered to stirnerist

disrespect to private property only recognizing property of one's own

spirit.[102].

Novatore collaborated in the individualist anarchist journal Iconoclasta!

alongside the young stirnerist illegalist

Bruno Filippi[103]

Spain

Spain

received the influence of American individualist anarchism but most

importantly it was related to the French currents. At the turn of the

century individualism in Spain takes force through the efforts of

people such as Dorado Montero, Ricardo Mella, Federico Urales and J.

Elizalde who will translatre French and American individualists[20].

Important in this respect were also magazines such as La Idea Libre,

La revista blanca,

Etica, Iniciales, Al margen and Nosotros.

The most influential thinkers there were Max

Stirner, Emile Armand and Han

Ryner. Just as in France, the spreading of Esperanto

had importance just as naturism and free

love currents[20].

Later

Armand and Ryner themselves will start writing in the Spanish

invidualist press. The concept of Armand of amorous chamaraderie had an

important role in motivating polyamory

as realization of the individual[20].

An important Spanish individualist anarchist was also Miguel Giménez Igualada who

wrote the lengthy theory book called Anarchism espousing his

individualist anarchism[104].

Recently spanish historian Xavier Diez

has dedicated extensive

research on spanish individualist anarchism as can be seen in his books

El anarquismo individualista en España: 1923-1938[105]

y Utopia sexual a la premsa anarquista de Catalunya. La revista

Ética-Iniciales(1927-1937) (which deals with free love

thought as present in the spanish individualist anarchist magazine Iniciales)[106].

Germany

In Germany

the Scottish-german John Henry McKay

became the most important propagandist for individualist anarchist

ideas. He fused stirnerist egoism with the positions of Benjamin Tucker

and actually translated Tucker into german. Two semi-fictional writings

of his own Die Anarchisten and Der

Freiheitsucher

contributed to individualist theory through an updating of egoist

themes within a consideration of the anarchist movement. English

translations of these works arrived in the United Kingdom and in

individualist American circles lead by Tucker[107].

McKay is also known as an important European early activist for LGBT rights.

Using the pseudonym

Sagitta, Mackay wrote a series of works for pederastic

emancipation,

titled Die Buecher der namenlosen Liebe (Books of the

Nameless Love). This series was conceived in 1905 and completed in

1913 and included the Fenny Skaller, a story of a pederast.[108]

Under the same pseudonym he also published fiction, such as Holland

(1924) and a pederastic novel of the Berlin

boy-bars, Der Puppenjunge (The Hustler) (1926).

Adolf

Brand (1874-1945) was a German

writer,

stirnerist anarchist

and pioneering campaigner for the

acceptance of male bisexuality and homosexuality.

Brand published a German homosexual periodical, Der

Eigene in 1896. This was the first ongoing homosexual

publication in the world[109].

The name was taken from writings of egoist philosopher Max

Stirner, who had greatly influenced the young Brand, and refers to

Stirner's concept of "self-ownership" of the individual. Der

Eigene

concentrated on cultural and scholarly material, and may have had an

average of around 1500 subscribers per issue during its lifetime,

although the exact numbers are uncertain. Contributors included Erich Mühsam, Kurt

Hiller, John Henry Mackay (under the pseudonym

Sagitta) and artists Wilhelm von Gloeden, Fidus and Sascha Schneider. Brand contributed many

poems and articles himself.

Russia

In Russia, Lev

Chernyi

was an important individualist anarchist involved in resistance against

the rise to power of the Bolchevik Party. He adhered mainly to Stirner

and the ideas of Benjamin Tucker. In 1907, he published a

book entitled Associational Anarchism, in which he advocated

the "free association of independent individuals."[110].

On

his return from Siberia in 1917 he enjoyed great popularity among

Moscow workers as a lecturer. Chernyi was also Secretary of the Moscow

Federation of Anarchist Groups, which was formed in March 1917[110].

He

died after being accused of participation in an episode in which

this group bombed the headquarters of the Moscow Committee of the

Communist Party. Although most likely not being really involved in the

bombing, he might have died of torture[110].

Chernyi advocated a Nietzschean overthrow of the values of

bourgeois Russian society, and rejected the voluntary communes of anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin as a threat to the freedom

of the individual.[111][112][113]

Scholars including Avrich and Allan Antliff have interpreted this

vision of society to have been greatly influenced by the individualist

anarchists Max Stirner, and Benjamin Tucker.[114]

Subsequent to the book's publication, Chernyi was imprisoned in Siberia

under the Russian Czarist regime for his

revolutionary activities.[115]

Latin

American individualist anarchism

Vicente Rojas Lizcano

pseudonym of Biófilo Panclasta,

was a Colombian individualist

anarchist writer and activist. In 1904

he begins using the name Biofilo Panclasta. "Biofilo" in spanish stands

for "lover of life" and "Panclasta" for "enemy of all". [116]

He visited more than fifty countries propagadizing for anarchism which

in his case was highly influenced by the thought of Max

Stirner and Friedrich Nietszche.

Among his written works there are Siete años enterrado vivo

en una de las mazmorras de Gomezuela: Horripilante relato de un

resucitado(1932) and Mis prisiones, mis destierros y mi vida

(1929) which talk about his many adventures while living his live as an

adventurer, activist and vagabond as well as his thought and the

many times he was imprisioned in different countries.

Maria Lacerda de Moura was a Brazilian

teacher,

journalist,

anarcha-feminist, and

individualist

anarchist. Her ideas regarding education were largely influenced by

Francisco Ferrer. She

later moved to São Paulo and became involved in

journalism for the anarchist and labor press. There she also lectured

on topics including education, women's rights, free

love, and antimilitarism. Her writings and essays

landed her attention not only in Brazil, but also in Argentina

and Uruguay.

In February 1923 she launched Renascença, a periodical

linked with the anarchist, progressive,

and freethinking circles of the period. Her

thought was mainly influenced by individualist

anarchists such as Han Ryner and Emile Armand[117].

Criticisms

Prior to abandoning anarchism,

libertarian socialist Murray Bookchin criticized individualist

anarchism for its opposition to democracy

and its embrace of "lifestylism" at the expense of class struggle.[118]

Bookchin claimed that individualist anarchism supports only negative liberty and rejects the idea of positive liberty.[119]

Anarcho-communist Albert Meltzer

proposed that individualist anarchism differs radically from

revolutionary anarchism, and that it "is sometimes too readily conceded

'that this is, after all, anarchism'." He claimed that Benjamin Tucker's

acceptance of the use of a private police force (including to break up

violent strikes to protect the "employer's 'freedom'") is contradictory

to the definition of anarchism as "no government."[120]

Meltzer opposed anarcho-capitalism

for similar reasons, arguing that since it supports "private armies",

it actually supports a "limited State." He contends that it "is only

possible to conceive of Anarchism which is free, communistic and

offering no economic necessity for repression of countering it."[121]

According to Gareth Griffith, George Bernard Shaw

initially had flirtations with individualist anarchism before coming to

the conclusion that it was "the negation of socialism, and is, in fact,

unsocialism carried as near to its logical conclusion as any sane man

dare carry it." Shaw's argument was that even if wealth was initially

distributed equally, the degree of laissez-faire

advocated by Tucker would result in the distribution of wealth becoming

unequal because it would permit private appropriation and accumulation.[122]

According to academic Carlotta Anderson, American individualist

anarchists accept that free competition results in unequal wealth

distribution, but they "do not see that as an injustice."[123]

Tucker explained, "If I go through life free and rich, I shall not cry

because my neighbor, equally free, is richer. Liberty will ultimately

make all men rich; it will not make all men equally rich. Authority may

(and may not) make all men equally rich in purse; it certainly will

make them equally poor in all that makes life best worth living."[124]

There is also criticism between

contemporary individualist anarchism currents. American mutualist Joe

Peacott

has criticized anarcho-capitalists for trying to hegemonize the label

"individualist anarchism" and make appear as if all individualist

anarchists are pro-capitalism[125].

He

has stated that "some individualists, both past and present, agree

with the communist anarchists that present-day capitalism is based on

economic coercion, not on voluntary contract. Rent and interest are

mainstays of modern capitalism, and are protected and enforced by the

state. Without these two unjust institutions, capitalism could not

exist."[126]

In this way he adheres to mutualist anti-capitalism.

See also

α^

The term "individualist anarchism" is often used as a classificatory

term, but in very different ways. Some sources, such as An Anarchist FAQ use the classification "social anarchism

/ individualist anarchism". Some see individualist anarchism as

distinctly non-socialist, and use the classification "socialist

anarchism / individualist anarchism" accordingly.[127]

Other classifications include "mutualist/communal" anarchism.[128]

β^

Michael Freeden identifies four broad types

of individualist anarchism. He says the first is the type associated

with William Godwin that advocates self-government with a

"progressive rationalism that included benevolence to

others." The second type is the amoral self-serving rationality of Egoism,

as most associated with Max

Stirner. The third type is "found in Herbert Spencer's early predictions, and

in that of some of his disciples such as Donisthorpe,

foreseeing the redundancy of the state in the source of social

evolution." The fourth type retains a moderated form of egoism and

accounts for social cooperation through the advocacy of market

relationships.[5]

γ^ See,

for example, the Winter 2006 issue of the Journal of Libertarian

Studies, dedicated to reviews of Kevin Carson's Studies in

Mutualist Political Economy. Mutualists compose one bloc, along

with agorists and geo-libertarians, in the recently formed Alliance of

the Libertarian Left.

δ^ Though

this term is non-standard usage – by "left", agorists mean "left" in

the general sense used by left-libertarians, as defined by Roderick T. Long, as "...

an

integration, or I’d argue, a reintegration of libertarianism with

concerns that are traditionally thought of as being concerns of the

left. That includes concerns for worker empowerment, worry about

plutocracy, concerns about feminism and various kinds of social

equality."[129]

ε^ Konkin

wrote the article "Copywrongs"in opposition to

the concept and Schulman countered SEK3's arguments in "Informational Property:

Logorights."

ζ^

Individualist

anarchism is also known by the terms "anarchist

individualism", "anarcho-individualism", "individualistic anarchism",

"libertarian anarchism",[130][131][132][133]

"anarcho-libertarianism",[134][135]

"anarchist libertarianism"[134]

and "anarchistic libertarianism".[136]

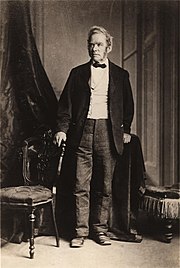

Murray

Rothbard

From Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

| Murray

Newton Rothbard |

Rothbard circa 1955 |

| Full name |

Murray Newton Rothbard |

| Born |

March 2, 1926(1926-03-02)

Bronx, New York,

United States |

| Died |

January 7, 1995 (aged 68)

New York City, New York, U.S.

|

| Era |

20th-century Economists

(Austrian Economics) |

| Region |

Western Economists |

| School |

Austrian School |

| Main interests |

Economics,

Political economy, Anarchism,

Natural law, Praxeology,

Numismatics, Philosophy of law, Ethics, Economic history |

| Notable ideas |

Founder of Anarcho-capitalism, Rothbard's law |

Aristotle,

Aquinas, Rand,

Mises, Menger,

Böhm-Bawerk, Molinari, Hayek, Say, Spooner, Tucker, Bastiat, Spencer, Nock, Oppenheimer, Locke,

Laozi,

Mencken, Burke,

Rose Wilder Lane, Frank Chodorov, Étienne de La Boétie

|

Hoppe, Friedman, Rockwell, Konkin, Narveson,

Heath, Callahan, Raico,

Salerno, Sobran,

McElroy, Tucker, Bylund, Long,

Caplan, Murphy, Lottieri, Woods,

Kinsella, Nozick,

Molyneux, Thornton, Scott Horton, Hülsmann, Raimondo, DiLorenzo, Block,

Linda &

Morris Tannehill, Paul, Robert

Higgs

|

Murray Newton Rothbard (March 2,

1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American intellectual,

individualist

anarchist,[1]

author,

and economist

of the Austrian School who helped define modern libertarianism and popularized a form of free-market anarchism he termed "anarcho-capitalism".[2][3]

Rothbard wrote over twenty books.

Building on the Austrian School's

concept of spontaneous order in markets, support

for a free market in money production and condemnation of central planning,[4]

Rothbard sought to minimize coercive

government control of the economy. He considered the monopoly

force of government the greatest danger to liberty and the long-term

wellbeing of the populace, labeling the State

as nothing but a "gang of thieves writ large" - the locus of the most

immoral, grasping and unscrupulous individuals in any society.[5][6][7][8]

Rothbard concluded that virtually all

services provided by monopoly governments

could be provided more efficiently by the private sector. He viewed

many regulations and laws ostensibly promulgated for the "public

interest" as self-interested power grabs by scheming government

bureaucrats engaging in dangerously unfettered self-aggrandizement, as

they were not subject to market disciplines which would quickly

eliminate such parasitic inefficiencies if they were to occur in the

competitive private sector.[9][10][11]

Rothbard was equally condemning of state

corporatism. He criticized

many instances where business elites co-opted government's monopoly

power so as to influence laws and regulatory policy in a manner

benefiting them at the expense of their competitive rivals.[12]

He argued that taxation represents coercive theft on a grand

scale, and "a compulsory monopoly

of force" prohibiting the more efficient voluntary procurement of

defense and judicial services from competing suppliers.[13][6]

He also considered central banking and fractional

reserve banking under a monopoly fiat money system a form of

state-sponsored, legalized financial fraud,

antithetical to libertarian principles and ethics.[14][15][16][17]

Rothbard opposed military, political, and economic interventionism in the

affairs of other nations.[18][19]

Life and work

Rothbard was born to David and Rae

Rothbard, who raised their Jewish family in the Bronx. "I grew up in a Communist culture," he

recalled.[20]

He attended Columbia University, where he was

awarded a Bachelor of Arts degree in mathematics

and economics in 1945 and a Master of Arts degree in

1946. He earned a Doctor of Philosophy degree in

economics in 1956 at Columbia under Joseph Dorfman.[21][22]

During the early 1950s, he studied under

the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises at his seminars at New York University and was greatly

influenced by Mises' book Human

Action. In the 1950s and 1960s he worked for the liberal William Volker Fund on a book project

that resulted in Man, Economy, and State,

published in 1962. From 1963 to 1985, he taught at Polytechnic

Institute of New York University in Brooklyn,

New

York. From 1986 until his death he was a distinguished professor at

the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Rothbard founded the Center for Libertarian Studies

in 1976 and the Journal of Libertarian Studies

in 1977. He was associated with the 1982 creation of the Ludwig von Mises Institute and

later was its academic vice president. In 1987 he started the scholarly

Review of Austrian Economics, now called the Quarterly Journal of

Austrian Economics.[21]

In 1953 in New

York City he married JoAnn Schumacher, whom he called the

"indispensable framework" for his life and work.[21]

He died in 1995 in Manhattan of a heart attack. The New York Times

obituary called Rothbard "an economist and social philosopher who

fiercely defended individual freedom against government intervention."[23]

Austrian School

writings

Cover of the 2004 edition of Man,

Economy, and State.

The Austrian School attempts to discover

axioms of human action (called "praxeology"

in the Austrian tradition). It supports free market economics

and criticizes command economies

because they destroy the delicate and complex dynamic information

function of fluctuating prices and inevitably lead to totalitarianism,

as government interventions cause inefficient distortions in markets,

requiring yet further intervention. Influential advocates were Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, Friedrich Hayek, and Ludwig von Mises.

Rothbard argued that the entire Austrian economic theory is the working

out of the logical implications of the fact that humans engage in

purposeful action.[24]

In working out these axioms he came to the position that a monopoly

price could not exist on the free market. He also anticipated much of

the “rational expectations”

viewpoint in economics. His free market views convinced him that

individual protection and national defense also should be offered on

the market, rather than supplied by government’s coercive monopoly.[21]

Rothbard was an ardent critic of Keynesian economic thought[25]

as well as the utilitarian theory of philosopher Jeremy Bentham.[26]

In Man, Economy, and State

Rothbard divides the various kinds

of state intervention in three categories: "autistic intervention",

which is interference with private non-exchange activities; "binary

intervention", which is forced exchange between individuals and the

state; and "triangular intervention", which is state-mandated exchange

between individuals. According to Sanford Ikeda, Rothbard's typology

"eliminates the gaps and inconsistencies that appear in Mises's

original formulation."[27][28]

Rothbard also was knowledgeable in

history and political philosophy. Rothbard's books, such as Man,

Economy, and State, Power and Market, The Ethics of Liberty, and For a New Liberty, are considered by

some to be classics of natural

law and libertarian thought,

combining libertarian natural rights

philosophy, anti-government anarchism

and a free market

perspective in analyzing a range of contemporary social and economic

issues. He also possessed extensive knowledge of the history of

economic thought, studying the pre-Adam

Smith free market economic schools, such as the Scholastics and the Physiocrats and discussed them in his

unfinished, multi-volume work, An

Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought.

Murray Rothbard points out in Power and Market

that the role of the economist in a free market is limited, but the

role and power of the economist in a government which continually

intervenes in the market expands, as the interventions trigger problems

which require further diagnosis and the need for further policy

recommendations. Murray argues that this simple self-interest

prejudices the views of many economists in favor of increased

government intervention.[29][30]

Rothbard also created "Rothbard's law"

that "people tend to specialize in what they are worst at. Henry

George, for example, is great on everything but land, so therefore

he writes about land 90% of the time. Friedman is great except on money, so he

concentrates on money."[31]

Political views

Rothbard "combined the laissez-faire

economics of his teacher Ludwig von Mises

with the absolutist views of human rights and rejection of the state he

had absorbed from studying the individualist American anarchists of the

nineteenth century such as Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker."[32]

He connected these to more modern views, writing: "There is, in the

body of thought known as 'Austrian economics',

a

scientific explanation of the workings of the free market (and of the

consequences of government intervention in that market) which

individualist anarchists could easily incorporate into their political

and social Weltanschauung."[33]

Rothbard opposed what he considered the

overspecialization of the

academy and sought to fuse the disciplines of economics, history,

ethics, and political science to create a "science of liberty."

Rothbard described the moral basis for his anarcho-capitalist position

in two of his books: For a New Liberty, published in

1972, and The Ethics of Liberty, published

in 1982. In his Power and Market (1970), Rothbard

described how a stateless economy would function.[34]

Self-ownership

In The Ethics of Liberty,

Rothbard asserted the right of total self-ownership, as the only principle

compatible with a moral code that applies to every person—a "universal

ethic"—and that it is a natural

law by being what is naturally best for man.[35]

He believed that, as a result, individuals owned the fruits of their

labor. Accordingly, each person had the right to exchange his property

with others. He believed that if an individual mixes his labor with

unowned land then he is the proper owner, and from that point on it is

private property that may only exchange hands by trade or gift. He also

argued that such land would tend not to remain unused unless it makes

economic sense to not put it to use.[36]

Anarcho-capitalism

Rothbard began to consider himself a

private property anarchist in the 1950s and later began to use "anarcho-capitalist."[37][38]

He wrote: "Capitalism is the fullest expression of anarchism, and

anarchism is the fullest expression of capitalism."[39]

In his anarcho-capitalist model, a system of protection agencies

compete in a free market and are voluntarily supported by consumers who

choose to use their protective and judicial services.

Anarcho-capitalism would mean the end of the state monopoly on force.[37]

Rothbard was equally condemning of the

corrupt and parasitic nexus

between big business and big government. He cited many instances where

business elites co-opted government's monopoly power so as to influence

laws and regulatory policy in a manner benefiting them at the expense

of their competitive rivals. He wrote in criticism of Ayn Rand's "misty

devotion to the Big Businessman" that she: "is too committed

emotionally to worship of the Big Businessman-as-Hero to concede that

it is precisely Big Business that is largely responsible for the

twentieth-century march into aggressive statism..."[40]

According to Rothbard, one example of such cronyism included grants of

monopolistic privilege the railroads derived from sponsoring so-called

conservation laws.[41]

He was also particularly critical of the influence big private banking

institutions/cartels had on Federal Reserve formation and policy.

Free market money

- See also Free banking and Gold

standard

Rothbard believed the monopoly power of

government over the issuance and distribution of money was

inherently destructive and unethical. The belief derived from Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek's Austrian

theory of the business cycle, which holds that undue credit expansion

inevitably leads to a gross misallocation of capital resources,

triggering unsustainable credit bubbles and, eventually, economic depressions.

He therefore strongly opposed central banking and fractional

reserve banking under a fiat

money system, labeling it as "legalized counterfeiting"[42]

or a form of institutionalized embezzlement

and therefore inherently fraudulent.[43][44]

He strongly advocated full reserve banking

("100 percent banking")[45]

and a voluntary, nongovernmental gold

standard[21][46]

or, as a second best solution, free

banking (which he also called "free market money").[47]

In relation to the current central

bank-managed fractional

reserve fiat currency system, he

stated the following:[48]

| “ |

Given this dismal

monetary

and banking situation, given a 39:1 pyramiding of checkable deposits

and currency on top of gold, given a Fed unchecked and out of control,

given a world of fiat moneys, how can we possibly return to a sound

noninflationary market money? The objectives, after the discussion in

this work, should be clear: (a) to return to a gold standard, a

commodity standard unhampered by government intervention; (b) to

abolish the Federal Reserve System and return to a system of free and

competitive banking; (c) to separate the government from money; and (d)

either to enforce 100 percent reserve banking on the commercial banks,

or at least to arrive at a system where any bank, at the slightest hint

of nonpayment of its demand liabilities, is forced quickly into

bankruptcy and liquidation. While the outlawing of fractional reserve

as fraud would be preferable if it could be enforced, the problems of

enforcement, especially where banks can continually innovate in forms

of credit, make free banking an attractive alternative. |

” |

Noninterventionism

Believing like Randolph Bourne that "war is the health of

the state" Rothbard opposed aggressive foreign policy.[21]

He criticized imperialism and the rise of the American empire which

needed war to sustain itself and to expand its global control. His

dislike of U.S. imperialism even led him to eulogize and lament the CIA-assisted

execution of Marxist revolutionary Che

Guevara in 1967, proclaiming that "his enemy was our enemy".[49]

Rothbard believed that stopping new wars was necessary and knowledge of

how government had seduced citizens into earlier wars was important.

Two essays expanded on these views "War, Peace, and the State" and "The

Anatomy of the State". Rothbard used insights of the elitism

theorists Vilfredo Pareto, Gaetano

Mosca, and Robert Michels to build a model of state

personnel, goals, and ideology.[50][51]

In an obituary for historian Harry Elmer Barnes Rothbard explained

why historical knowledge is important:[52]

| “ |

Our entry into World

War II

was the crucial act in foisting a permanent militarization upon the

economy and society, in bringing to the country a permanent garrison

state, an overweening military-industrial complex, a permanent system

of conscription. It was the crucial act in creating a mixed economy run

by Big Government, a system of state-monopoly capitalism run by the

central government in collaboration with Big Business and Big Unionism. |

” |

Rothbard discussed his views on the

principles of a libertarian

foreign policy in a 1973 interview: "minimize State power as much as

possible, down to zero, and isolationism is the full expression in

foreign affairs of the domestic objective of whittling down State

power." He further called for "abstinence from any kind of American

military intervention and political and economic intervention."[18]

In For a New Liberty

he writes: "In a purely libertarian world, therefore, there would be no

'foreign policy' because there would be no States, no governments with

a monopoly of coercion over particular territorial areas."[53]

In "War Guilt in the Middle East"

Rothbard details Israel's

"aggression against Middle East Arabs," confiscatory policies and its

"refusal to let these refugees return and reclaim the property taken

from them."[54]

Rothbard also criticized the “organized Anti-Anti-Semitism” that

critics of the state of Israel have to suffer.[55]

Rothbard criticized as terrorism

the actions of the United States, Israel, and any nation that

"retaliates" against innocents because they cannot pinpoint actual

perpetrators. He held that no retaliation that injures or kills

innocent people is justified, writing "Anything else is an apologia for

unremitting and unending mass murder."[56]

Children and rights

In the Ethics of Liberty

Rothbard explores in terms of

self-ownership and contract several contentious issues regarding

children's rights. These include women's right to abortion,

proscriptions on parents aggressing against children once they are

born, and the issue of the state forcing parents to care for children,

including those with severe health problems. He also holds children

have the right to "run away" from parents and seek new guardians as

soon as they are able to choose to do so. He suggested parents have the

right to put a child out for adoption or even sell the rights to the

child in a voluntary contract, which he feels is more humane than

artificial governmental restriction of the number of children available

to willing and often superior parents. He also discusses how the

current juvenile justice system punishes children for making "adult"

choices, removes children unnecessarily and against their will from

parents, often putting them in uncaring and even brutal foster care or

juvenile facilities.[57][58]

Political activism

As a young man, Rothbard considered

himself part of the Old Right, an anti-statist and

anti-interventionist branch

of the U.S. Republican party.

When interventionist cold

warriors of the National Review, such as William F. Buckley, Jr., gained

influence in the Republican party in the 1950s, Rothbard quit the

party. After Rothbard passed away, William F. Buckley

wrote a bitter obituary in the National Review criticizing

Rothbard's "defective judgement" and views on the Cold War.[59]

During the late 1950s, Rothbard was an

associate of Ayn Rand and her Objectivist philosophy, but later

left her inner circle. He later lampooned the relationship in his play Mozart Was a Red. In the late 1960s,

Rothbard advocated an alliance with the New Left

anti-war movement, on the grounds that the conservative movement had

been completely subsumed by the statist establishment. However,

Rothbard later criticized the New Left for supporting a "People's

Republic" style draft. It was during this phase that he associated with

Karl

Hess and founded Left and

Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought with Leonard Liggio and George Resch, which

existed from 1965 to 1968. From 1969 to 1984 he edited The Libertarian Forum, also

initially with Hess (although Hess's involvement ended in 1971).

Rothbard criticized the "frenzied

nihilism" of left-wing

libertarians, but also criticized right-wing libertarians who were

content to rely only on education to bring down the state; he believed

that libertarians should adopt any non-immoral tactic available to them

in order to bring about liberty.[60]

During the 1970s and 1980s, Rothbard was

active in the Libertarian

Party.

He was frequently involved in the party's internal politics. From 1978

to 1983, he was associated with the Libertarian Party Radical Caucus,

allying himself with Justin Raimondo, Eric

Garris and Williamson Evers. He opposed the "low tax

liberalism" espoused by 1980 Libertarian Party presidential candidate Ed Clark

and Cato Institute president Edward H

Crane III.

Rothbard split with the Radical Caucus at the 1983 national convention

over cultural issues, and aligned himself with what he called the

"rightwing populist" wing of the party, notably Lew

Rockwell and Ron Paul, who ran for President on the

Libertarian Party ticket in 1988 and in the 2008

Republican Party Primaries.

In 1989, Rothbard left the Libertarian

Party and began building bridges to the post-Cold War

anti-interventionist right, calling himself a paleolibertarian.[61]

He was the founding president of the conservative-libertarian John Randolph Club and supported the

presidential campaign of Pat

Buchanan in 1992, saying "with Pat Buchanan as our leader, we shall

break the clock of social democracy."[62]

However, later he became disillusioned and said Buchanan developed too

much faith in economic planning and centralized state power.[63]

Books

Cover from the first volume of the 2006

Ludwig Von

Mises Institute edition of

An Austrian Perspective on the

History of Economic Thought

- Man, Economy, and State (Full Text; ISBN 0-945466-30-7) (1962)

- The Panic of 1819. 1962, 2006

edition: ISBN 1-933550-08-2.

- America's Great Depression.

(Full Text) ([ISBN 0-945466-05-6. (1963,

1972, 1975, 1983, 2000)

- What Has Government

Done to Our Money? (Full Text / Audio Book) ISBN 0-945466-44-7. (1963)

- Economic Depressions: Causes and Cures (1969)

- Power and Market. ISBN 1-933550-05-8. (1970)

(restored to Man, Economy, and State ISBN 0-945466-30-7, 2004)

- Education: Free and Compulsory. ISBN 0-945466-22-6. (1972)

- Left and Right, Selected Essays 1954-65 (1972)

- For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto

(Full text / Audio book) ISBN 0-945466-47-1. (1973, 1978)

- The Essential von Mises (1973)

- The Case for the 100 Percent Gold Dollar. ISBN 0-945466-34-X. (Full Text / Audio Book) (1974)

- Egalitarianism

as a Revolt Against Nature and Other Essays ISBN 0-945466-23-4. (1974)

- Conceived in Liberty (4 vol.) ISBN 0-945466-26-9. (1975-79)

- Individualism and the Philosophy of the Social Sciences. ISBN 0-932790-03-8. (1979)

- The Ethics of Liberty (Full Text / Audio Book) ISBN 0-8147-7559-4. (1982)

- The Mystery of Banking ISBN 0-943940-04-4. (1983)

- Ludwig von Mises: Scholar, Creator, Hero. OCLC 20856420. (1988)

- Freedom, Inequality, Primitivism, and the Division of Labor.

Full text (included as Chapter 16 in Egalitarianism

above) (1991)

- The Case Against the Fed ISBN 0-945466-17-X. (1994)

- An

Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought (2

vol.) ISBN 0-945466-48-X. (1995)

- Wall Street, Banks, and American Foreign Policy. (Full Text) with an introduction by Justin Raimondo. (1995)

- Making Economic Sense. ISBN 0-945466-18-8. (1995, 2006)

- Logic of Action (2 vol.) ISBN 1-85898-015-1 and ISBN 1-85898-570-6. (1997, to

be reprinted as Economic Controversies in 2009)

- The Austrian Theory of the Trade Cycle and Other Essays. ISBN 0-945466-21-8. (also by

Mises, Hayek, & Haberler)

- Irrepressible Rothbard: The Rothbard-Rockwell Report Essays of

Murray N. Rothbard. (Full Text.) (Preface by JoAnn Rothbard) (Introduction by Lew

Rockwell.) ISBN 1-883959-02-0. (2000)

- A History of Money and Banking in the United States.

ISBN 0-945466-33-1. (2005)

- The Complete Libertarian Forum

(2 vol.) (Full Text) ISBN 1-933550-02-3. (1969-84;

2006)

- The Betrayal of the

American Right ISBN 978-1-933550-13-8 (2007)

See also

American

philosophy

From Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

American philosophy is the philosophical activity or output of Americans,

both within the United States and abroad. The Internet Encyclopedia of

Philosophy

notes that while American philosophy lacks a "core of defining

features, American Philosophy can nevertheless be seen as both

reflecting and shaping collective American identity over the history of

the nation."[1]

17th century

The American philosophical tradition

began at the time of the European colonization

of the New World.[1]

The Puritan

arrival in New York

set the earliest American philosophy into the religious tradition, and

there was also an emphasis on the relationship between the individual

and the community. This is evident by the early colonial documents such

as the Fundamental Orders of

Connecticut (1639) and the Massachusetts Body of Liberties

(1641).[1]

Thinkers such as John Winthrop

emphasized the public life over the private, holding that the former

takes precedence over the latter, while other writers, such as Roger Williams (co-founder of Rhode

Island) held that religious tolerance

was more integral than trying to achieve religious homogeneity in a

community.[2]

18th century

18th century American philosophy is

often broken into two halves, the earlier half being marked by Puritan Calvinism,

and the latter characterized by the American incarnation of the European

Enlightenment that is associated with the political thought of

the Founding Fathers.[1]

Calvinism

Jonathan Edwards is

considered to be "America's most important and original philosophical

theologian."[3]

Noted for his energetic sermons, such as "Sinners in the Hands of

an Angry God" (which is said to have begun the First Great Awakening), Edwards

emphasized "the absolute sovereignty of God and the beauty of God's

holiness."[3]

Working to unite Christian Platonism

with an empiricist epistemology,

with the aid of Newtonian physics,

Edwards was deeply influenced by George Berkeley,

himself an empiricist, and Edwards derived his importance of the

immaterial for the creation human experience from Bishop Berkeley. The

non-material mind consists of understanding and will, and it is

understanding, interpreted in a Newtonian framework, that leads to

Edwards' fundamental metaphysical category of Resistance. Whatever

features an object may have, it has these properties because the object

resists. Resistance itself is the exertion of God's power, and it can

be seen in Newton's laws of motion,

where an object is "unwilling" to change its current state of motion;

an object at rest will remain at rest and an object in motion will

remain in motion.

As a Calvinist and hard determinist,

Jonathan Edwards also rejected the freedom

of the will,

saying that "we can do as we please, but we cannot please as we

please." According to Edwards, neither good works nor self-originating

faith lead to salvation, but rather it is the unconditional grace of

God which stands as the sole arbiter of human fortune.

The Age of

Enlightenment

While the early 18th century American

philosophical tradition was

decidedly marked by religious themes, the latter half saw a reliance on

reason

and science,

and, in step with the thought of the Age of Enlightenment, a belief in the

perfectibility of human beings, laissez-faire

economics,

and a general focus on political matters.[1]

The Founding Fathers,

namely Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and James

Madison,

wrote extensively on political issues. In continuing with the chief

concerns of the Puritans in the 17th century, the Founding Fathers

debated the relationship between the individual and the state, as well

as the nature of the state, importantly concerning the state's

relationship to God and religion. It was at this time that the United States

Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution were

written, and they are the result of debate and compromise. The

Constitution sets forth a federated republican

form of government that is marked by a balance of powers

accompanied by a checks and balances

system between the three branches of government: a judicial branch, an executive branch led