Post-left

anarchy

From Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

Post-left anarchy is a recent

current in anarchist thought that

promotes a critique of anarchism's relationship to traditional leftism. Some post-leftists seek to

escape the confines of ideology in general also presenting a critique of

organizations and morality[1].

Post-left anarchy is marked by a focus on social insurrection and a rejection of

leftist social organisation.[2]

influenced by the work of Max

Stirner[1]

and by the Situationist International[1].

The magazines Anarchy: A Journal of

Desire Armed, Green

Anarchy and Fifth Estate have been

involved in developing post-left anarchy. Individual writers associated

with the tendency are Hakim Bey, Bob

Black, John Zerzan, Jason

McQuinn, Fredy Perlman, Lawrence Jarach and Wolfi Landstreicher. The contemporary

network of collectives CrimethInc.

is an exponent of post-left anarchist views.

Overview

The left,

even the revolutionary left, post-leftists argue, is anachronistic and

incapable of creating change. Post-left anarchy offers critiques of

radical strategies and tactics which it considers antiquated: the

demonstration, class-oriented struggle, focus on tradition, and the

inability to escape the confines of history. The book Anarchy in

the Age of Dinosaurs,

for example, criticizes traditional leftist ideas and classical

anarchism while calling for a rejuvenated anarchist movement. The CrimethInc.

essay "Your Politics Are Boring as Fuck" is another critique of

"leftist" movements:

Why has the oppressed proletariat

not come to its senses and joined you in your fight for world

liberation? ... [Because] they know that your antiquated styles of

protest – your marches, hand held signs, and gatherings – are

now

powerless to effect real change because they have become such a

predictable part of the status quo. They know that your post-Marxist

jargon is off-putting because it really is a language of mere academic

dispute, not a weapon capable of undermining systems of control…

—Nadia C., "Your Politics Are

Boring as Fuck"[3]

Some post-anarchists have come to similar

conclusions, if for different reasons:

There is a certain litany of oppressions which most radical

theories

are obliged to pay homage to. Why is it when someone is asked to talk

about radical politics today one inevitably refers to this same tired,

old list of struggles and identities? Why are we so unimaginative

politically that we cannot think outside of this 'shopping list' of

oppressions?

—Saul

Newman, From Bakunin to Lacan, p. 171[4]

Thought

Theory

& Critique of Organization

Jason

McQuinn

describes the left wing organizational tendency of "“transmission-belt”

structure with an explicit division between leaders and led, along with

provisions to discipline rank and file members while shielding leaders

from responsibility to those being led, more than a few people wise up

to the con game and reject it".[5]

For him there are 4 results out of such structure:

- Reductionism: Here "Only particular aspects of the social

struggle are included in these organizations. Other aspects are

ignored, invalidated or repressed, leading to further and further

compartmentalization of the struggle. Which in turn facilitates

manipulation by elites and their eventual transformation into purely

reformist lobbying societies with all generalized, radical critique

emptied out."[1]

- Specialization or Professionalism: This calls to attention

to the tendency where "Those most involved in the day-to-day operation

of the organization are selected—or self-selected—to perform

increasingly specialized roles within the organization, often leading

to an official division between leaders and led, with gradations of

power and influence introduced in the form of intermediary roles

in

the evolving organizational hierarchy."[1]

- Substitutionism where "The formal organization

increasingly

becomes the focus of strategy and tactics rather than the

people-in-revolt. In theory and practice, the organization tends to be

progressively substituted for the people, the organization's

leadership—especially if it has become formal—tends to substitute

itself for the organization as a whole, and eventually a maximal leader

often emerges who ends up embodying and controlling the

organization."[1]

- Ideology where "The organization becomes the primary

subject

of theory with individuals assigned roles to play, rather than people

constructing their own self-theories. All but the most self-consciously

anarchistic formal organizations tend to adapt some form of

collectivist ideology, in which the social group at some level is

acceded to have more political reality than the free individual.

Wherever sovereignty lies, there lies political authority; if

sovereignty is not dissolved into each and every person it always

requires the subjugation of individuals to a group in some form."[1].

To counter these tendencies post-left

anarchy advocates Individual and Group Autonomy

with Free Initiative, Free Association,

Refusal of Political Authority, and thus of Ideology, Small, Simple,

Informal, Transparent and Temporary Organization, and Decentralized,

Federal Organization with Direct Decision-Making and Respect for

Minorities[1].

The

critique of ideology(ies)

Post left anarchy adheres to a critique

of ideology that "dates from the work of Max

Stirner"[1].

For Jason McQuinn

"All ideology in essence involves the substitution of alien (or

incomplete) concepts or images for human subjectivity. Ideologies are

systems of false consciousness in which people no longer see themselves

directly as subjects in their relation to their world. Instead they

conceive of themselves in some manner as subordinate to one type or

another of abstract entity or entities which are mistaken as the real

subjects or actors in their world." "Whether the abstraction is God,

the State, the Party, the Organization, Technology, the Family,

Humanity, Peace, Ecology, Nature, Work, Love, or even Freedom; if it is

conceived and presented as if it is an active subject with a being of

its own which makes demands of us, then it is the center of an

ideology."[1]

The rejection of

morality

Morality is also a target of post-left

anarchy just as it was in Stirner[1]

and in the work of Friedrich Nietzsche.

For McQuinn "Morality is a system of reified values—abstract values

which are taken out of any context, set in stone, and converted into

unquestionable beliefs to be applied regardless of a person's actual

desires, thoughts or goals, and regardless of the situation in which a

person finds him- or herself. Moralism is the practice of not only

reducing living values to reified morals, but of considering oneself

better than others because one has subjected oneself to morality

(self-righteousness), and of proselytizing for the adoption of morality

as a tool of social change."[1]

Living up to morality means sacrificing certain desires and temptations

(regardless of the actual situation you might find yourself in) in

favor of the rewards of virtue.[1]

So "Rejecting Morality involves

constructing a critical theory of

one's self and society (always self-critical, provisional and never

totalistic) in which a clear goal of ending one's social alienation is

never confused with reified partial goals. It involves emphasizing

what people have to gain from radical critique and solidarity rather

than what people must sacrifice or give up in order to live virtuous

lives of politically correct morality."[1]

Critique of

identity politics

Post-left anarchy tends to criticize what

it sees as the partial victimizing views of identity politics.

Feral Faun thus writes in "The ideology of victimization" that

there´s

a "feminist version of the ideology of victimization- an ideology which

promotes fear, individual weakness (and subsequently dependence on

ideologically based support groups and paternalistic protection from

the authorities)"[6]

But in the end "Like all ideologies, the varieties of the ideology of

victimization are forms of fake consciousness. Accepting the social

role of victim—in whatever one of its many forms—is choosing to not

even create one's life for oneself or to explore one's real

relationships to the social structures. All of the partial liberation

movements--feminism, gay liberation, racial liberation, workers´ movements

and so on—define individuals in terms of their social roles. Because of

this, these movements not only do not include a reversal of

perspectives which breaks down social roles and allows individuals to

create a praxis built on their own passions and desires; they actually

work against such a reversal of perspective. The 'liberation' of a

social role to which the individual remains subject."[6]

The refusal of work

The issues of work, the division of labor

and the refusal of work has been an important

issue in post-left anarchy[7][8].

Bob

Black in "The Abolition of Work" calls

for the abolition of the producer- and consumer-based

society, where, Black contends, all of life is devoted to the production

and consumption of commodities[9].

Attacking Marxist state socialism as much as market capitalism,

Black

argues that the only way for humans to be free is to reclaim

their time from jobs and employment, instead turning necessary

subsistence tasks into free play done voluntarily - an approach

referred to as "ludic". The essay argues that "no-one should ever

work", because work - defined as compulsory productive activity

enforced by economic or political means - is the source of most of the

misery in the world.[9]

Most workers, he states, are dissatisfied with work (as evidenced by

petty deviance on the job), so that what he says should be

uncontroversial; however, it is controversial only because people are

too close to the work-system to see its flaws[9].

Play, in contrast, is not necessarily

rule-governed, and is performed voluntarily, in complete freedom, as a gift

economy. He points out that hunter-gatherer societies are typified by

play, a view he backs up with the work of Marshall Sahlins;

he recounts the rise of hierarchal societies, through which work is

cumulatively imposed, so that the compulsive work of today would seem

incomprehensibly oppressive even to ancients and medieval peasants.[9]

He responds to the view that "work," if not simply effort or energy, is

necessary to get important but unpleasant tasks done, by claiming that

first of all, most important tasks can be rendered ludic, or "salvaged"

by being turned into game-like and craft-like activities, and secondly

that the vast majority of work does not need doing at all.[9]

The latter tasks are unnecessary because they only serve functions of

commerce and social control that exist only to maintain the work-system

as a whole. As for what is left, he advocates Charles Fourier's approach of arranging

activities so that people will want to do them.[9]

He is also skeptical but open-minded about the possibility of

eliminating work through labour-saving technologies. He feels the left

cannot go far enough in its critiques because of its attachment to

building its power on the category of workers, which requires a valorization of work.[9]

Self-Theory

Post-left anarchists reject all

ideologies in favor of the individual and communal construction of

self-theory[1].

Individual

self-theory is theory in which the integral

individual-in-context (in all her or his relationships, with all her or

his history, desires, and projects, etc.) is always the subjective

center of perception, understanding and action[1].

Communal

self-theory is similarly based on the group as subject, but

always with an underlying awareness of the individuals (and their own

self-theories) which make up the group or organization[1].

For

McQuinn "Non-ideological, anarchist organizations (or informal

groups) are always explicitly based upon the autonomy of the

individuals who construct them, quite unlike leftist organizations

which require the surrender of personal autonomy as a prerequisite for

membership".[1]

Daily life,

creation of situations and immediatism

For Wolfi Landstreicher

"The reappropriation of life on the social level, as well as its full

reappropriation on the individual level, can only occur when we stop

identifying ourselves essentially in terms of our social identities."[10]

So "The recognition that this trajectory must be brought to an end and

new ways of living and relating developed if we are to achieve full

autonomy and freedom."[11]

So relationships with others are not seen anymore as in activism in

which the goal is "to seek followers who accept one’s position"[12]

but instead "comrades and accomplices with which to carry on one’s

explorations".[13]

So Hakim

Bey advocates not having to "wait for the revolution" and inmmediately

start "looking for "spaces" (geographic, social, cultural, imaginal)

with potential to flower as autonomous zones--and

we are looking for times in which these spaces are relatively open,

either through neglect on the part of the State or because they have

somehow escaped notice by the mapmakers, or for whatever reason."[14]

Ultimately "face-to-face, a group of humans synergize their efforts to

realize mutual desires, whether for good food and cheer, dance,

conversation, the arts of life; perhaps even for erotic pleasure, or to

create a communal artwork, or to attain the very transport of bliss--

in short, a "union of egoists" (as Stirner put it) in its simplest form--or else,

in Kropotkin's terms, a basic biological drive to

"mutual

aid." [15]

Relationship

with other tendencies within anarchism

Post-left anarchism has been critical of

more classical schools of anarchism such as platformism[16]

and anarcho-syndicalism[17].

A certain close relationship exists between post-left anarchy and anarcho-primitivism, individualist anarchism[18][19]

and insurrectionary anarchism.

Nevertheless post-left anarchists Wolfi Landstreicher[20]

and Jason McQuinn[21]

have distanced themselves from and criticized anarcho-primitivism as

"ideological".

Platformism

On platformism

Bob

Black

has said that "It attests to the ideological bankruptcy of the

organizational anarchists today that they should exhume (not resurrect)

a manifesto which was already obsolete when promulgated in 1926. The

Organizational Platform enjoys an imperishable permanence: untimely

then, untimely now, untimely forever. Intended to persuade, it elicited

attacks from almost every prominent anarchist of its time. Intended to

organize, it provoked splits. Intended to restate the anarchist

alternative to Marxism, it restated the Leninist alternative to anarchism. Intended to

make history, it barely made it into the history books."[22]

For Black "The result is yet another sect."[23]

Anarcho-syndicalism

Feral Faun has stated that "The anarcho-syndicalists

may talk of abolishing the state, but they will have to reproduce every

one of its functions to guarantee the smooth running of their society."

So "Anarcho-syndicalism does not make a radical break with the present

society. It merely seeks to extend this society´s values so they

dominate us more fully in our daily lives." Thus "the bourgeois liberal

is content to get rid of priests and kings, and the anarcho-syndicalist

throws in presidents and bosses. But the factories remain intact, the

stores remain intact (though the syndicalists may call them

distribution centers), the family remains intact — the entire social

system remains intact. If our daily activity has not significantly

changed — and the anarcho-syndicalists give no indication of wanting to

change it beyond adding the burden of managing the factories to that of

managing the factories to that of working in them — then what

difference does it make if there are no bosses? — We're still slaves!"[24]

The

issue of "lifestyle anarchism"

Beginning in 1997, Bob

Black became involved in a debate sparked by the work of anarchist

and founder of the Institute for Social Ecology Murray Bookchin, an outspoken critic of

the post-left anarchist

tendency. Bookchin wrote and published Social

Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm,

labeling post-left anarchists and others as "lifestyle anarchists"

- thus following up a theme developed in his Philosophy

of Social Ecology.

Though he does not refer directly to Black's work (an omission which

Black interprets as symptomatic), Bookchin clearly has Black's

rejection of work as an implicit target when he criticises authors such

as John Zerzan and Dave Watson, whom he

controversially labels part of the same tendency.

For Bookchin, "lifestyle anarchism" is

individualistic and childish.

"Lifestyle anarchists" demand "anarchy now", imagining they can create

a new society through individual lifestyle changes. In his view this is

a kind of fake-dissident consumerism which ultimately has no impact on

the functioning of capitalism because it fails to recognise the

realities of the present. He grounds this polemic in a social-realist

critique of relativism, which he associates with lifestyle anarchism as

well as postmodernism

(to which he claims it is related). Ludic approaches, he claims, lead

to social indifference and egotism similar to that of capitalism.

Against this approach, he advocates a variety of anarchism in which

social struggles take precedence over individual actions, with the

evolution of the struggle emerging dialectically as in classical

Marxist theory. The unbridgeable chasm of the book's title is between

individual "autonomy" - which for Bookchin is a bourgeois illusion - and social "freedom",

which implies direct democracy,

municipalism, and leftist concerns with social opportunities. In

practice his agenda takes the form of a combination of elements of anarchist communism with a support for

local-government and NGO initiatives which he refers to as Libertarian

Municipalism.

He claims that "lifestyle anarchism" goes against the fundamental

tenets of anarchism, accusing it of being "decadent" and

"petty-bourgeois" and an outgrowth of American decadence and a period

of declining struggle, and speaks in nostalgic terms of "the Left that

was" as, for all its flaws, vastly superior to what has come since.

In response, Black published Anarchy

After Leftism which later became a seminal post-left work.[25]

The text is a combination of point-by-point, almost legalistic

dissection of Bookchin's argument, with bitter theoretical polemic, and

even personal insult against Bookchin (whom he refers to as "the Dean"

throughout). Black accuses Bookchin of moralism, which in post-left

anarchism, refers to the imposition of abstract categories on reality

in ways which twist and repress desires (as distinct from "ethics",

which is an ethos of living similar to Friedrich Nietzsche's call for an

ethic "beyond good and evil"), and of "puritanism", a variant of this.

He attacks Bookchin for his Stalinist

origins, and his failure to renounce his own past affiliations with

what he himself had denounced as "lifestylist" themes (such as the

slogans of May 1968). He claims that the

categories of "lifestyle anarchism" and "individualist anarchism" are straw-men. He

alleges that Bookchin adopts a "work

ethic", and that his favored themes, such as the denunciation of Yuppies,

actually repeat themes in mass consumer culture, and that he fails to

analyze the social basis of capitalist "selfishness"; instead, Black

calls for an enlightened "selfishness" which is simultaneously social,

as in Max Stirner's work.

Bookchin, Black claims, has misunderstood

the critique of work as

asocial, when in fact it proposes non-compulsive social relations. He

argues that Bookchin believes labour to be essential to humans, and

thus is opposed to the abolition of work. And he takes him to case for

ignoring Black's own writings on work, for idealizing technology, and

for misunderstanding the history of work.

He denounces Bookchin's alleged failure

to form links with the

leftist groups he now praises, and for denouncing others for failings

(such as not having a mass audience, and receiving favourable reviews

from "yuppie" magazines) of which he is himself guilty. He accuses

Bookchin of self-contradiction, such as calling the same people

"bourgeois" and "lumpen", or "individualist" and "fascist". He alleges

that Bookchin's "social freedom" is "metaphorical" and has no real

content of freedom. He criticizes Bookchin's appropriation of the

anarchist tradition, arguing against his dismissal of authors such as

Stirner and Paul Goodman, rebuking Bookchin for

implicitly identifying such authors with anarcho-capitalism,

and defending what he calls an "epistemic break" made by the likes of

Stirner and Nietzsche. He alleges that the post-left "disdain for

theory" is simply Bookchin's way of saying they ignore his own

theories. He offers a detailed response to Bookchin's accusation of an

association of eco-anarchism with fascism via a supposed common root in

German romanticism, criticising both the derivation of the link (which

he terms "McCarthyist") and the portrayal of romanticism

itself, suggesting that Bookchin's sources such as Mikhail Bakunin

are no more politically correct than those he denounces, and accusing

him of echoing fascist rhetoric and propaganda. He provides evidence to

dispute Bookchin's association of "terrorism" with individualist rather than social anarchism. He points to

carnivalesque aspects of the Spanish Revolution to undermine

Bookchin's dualism.

Black then rehearses the post-left

critique of organization, drawing on his knowledge of anarchist history

in an attempt to rebut

Bookchin's accusation that anti-organizationalism is based in

ignorance. He claims among other things that direct democracy is

impossible in urban settings, that it degenerates into bureaucracy, and

that organizationalist anarchists such as the Confederación

Nacional del Trabajo

sold out to state power. He argues that Bookchin is not an anarchist at

all, but rather, a "municipal statist" or "city-statist" committed to

local government by a local state - smattering his discussion with

further point-by-point objections (for instance, over whether New York

is an "organic community" given the alleged high crime-rate and whether

confederated municipalities are compatible with direct democracy). He also takes up

Bookchin's opposition to relativism,

arguing

that this is confirmed by science, especially anthropology -

proceeding to produce evidence that Bookchin's work has received

hostile reviews in social-science journals, thus attacking his

scientific credentials, and to denounce dialectics as unscientific. He

then argues point-by-point with Bookchin's criticisms of primitivism,

debating issues such as life-expectancy statistics and alleged

ecological destruction by hunter-gatherers. And he concludes with a

clarion-call for an anarchist paradigm-shift based on post-left themes,

celebrating this as the "anarchy after leftism" of the title.

Bookchin never replied to Black's

critiques, which he continued in

such essays as "Withered Anarchism," "An American in Paris," and

"Murray Bookchin and the Witch-Doctors." Bookchin later repudiated

anarchism in favor of a form of direct democracy he called

"communalism".

Anarcho-primitivism

A certain close relationship exists

between post-left anarchy and anarcho-primitivism since

anarcho-primitivists such as John

Zerzan and the magazine Green

Anarchy have adhered and contributed to the post-left anarchy

perspective. Nevertheless post-left anarchists such as Jason

McQuinn and Feral

Faun/Wolfi Landstreicher[26]

have distanced themselves from and have criticized anarcho-primitivism.

Wolfi Landstreicher

has criticized the "ascetic morality of sacrifice or of a mystical

disintegration into a supposedly unalienated oneness with Nature,"[27]

which appears in anarcho-primitivism and deep

ecology. Jason McQuinn

has criticized what he sees an ideological tendency in

anarcho-primitivism when he says that "for most primitivists an

idealized, hypostatized vision of primal societies tends to

irresistibly displace the essential centrality of critical self-theory,

whatever their occasional protestations to the contrary. The locus of

critique quickly moves from the critical self-understanding of the

social and natural world to the adoption of a preconceived ideal

against which that world (and one's own life) is measured, an

archetypally ideological stance. This nearly irresistible

susceptibility to idealization is primitivism's greatest weakness."[28]

Individualist

anarchism

Murray Bookchin has identified post-left

anarchy as a form of individualist anarchism in Social

Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm

where he says he identifies "a shift among Euro-American anarchists

away from social anarchism and toward individualist or lifestyle

anarchism. Indeed, lifestyle anarchism today is finding its principal

expression in spray-can graffiti, post-modernist nihilism,

antirationalism, neoprimitivism, anti-technologism, neo-Situationist `cultural

terrorism,' mysticism, and a `practice' of staging Foucauldian `personal insurrections.'"[29]

A strong relationship does exist with

post-left anarchism and the work of individualist anarchist Max

Stirner. Jason McQuinn

says that "when I (and other anti-ideological anarchists) criticize

ideology, it is always from a specifically critical, anarchist

perspective rooted in both the skeptical, individualist-anarchist

philosophy of Max Stirner[19].

Also Bob

Black and Feral Faun/Wolfi Landstreicher strongly adhere to

stirnerist egoist anarchism. Bob Black has

humorously suggested the idea of "marxist stirnerism"[30].

Hakim

Bey has said "From Stirner's "Union of Self-Owning Ones" we proceed

to Nietzsche's circle of "Free Spirits" and

thence to Charles Fourier's "Passional Series",

doubling and redoubling ourselves even as the Other multiplies itself

in the eros of the group."[19]

As far as posterior individualist

anarchists Jason McQuinn for some time used the pseudonym Lev

Chernyi in honor of the Russian individualist anarchist of the same

name while Feral Faun has quoted

Italian individualist anarchist Renzo Novatore[31]

and has translated both Novatore[32]

and the young Italian individualist anarchist Bruno

Filippi[33].

Anarcha-feminism

Recently the anarcho-primitivist

anarcha-feminist

Lilith has published writings from a post-left anarchist perspective[34].

In "Gender Disobedience: Antifeminism and Insurrectionist Non-dialogue"

(2009) she has criticized Wolfi Landstreicher

position on feminism saying "I feel that an anarchist critique of

feminism may be valuable and illuminating. What I do not wish for is

more of the same anti-intellectualism and non-thought that seems to be

the lot of post-Leftist critiques of feminist theory."[35]

She along with other authors published BLOODLUST: a feminist

journal against civilization[36]

Insurrectionary

anarchism

Feral Faun (later writing as Wolfi Landstreicher) gained notoriety

as he wrote articles that appeared in the post-left

anarchy magazine Anarchy: A Journal of

Desire Armed. Post-left anarchy has held similar critiques of

organization as insurrectionary anarchism as can be seen in the work of

Wolfi Landstreicher and Alfredo Maria Bonanno.

John

Zerzan has said when speaking of Italian insurrectionary

anarchist

Alfredo Maria Bonanno that "Maybe insurrectionalism is less an ideology

than an undefined tendency, part left and part anti-left but generally

anarchist."[37]

Relationships

with schools of thought outside anarchism

McQuinn has said that "Those seeking to

promote the synthesis have

been primarily influenced by both the classical anarchist movement up

to the Spanish Revolution

on the one hand, and several of the most promising critiques and modes

of intervention developed since the 60s. The most important critiques

involved include those of everyday life and the spectacle,

of ideology and morality, of industrial technology, of work and of

civilization. Modes of intervention focus on the concrete deployment of

direct action in all facets of life."[1]

Thus the thought of the Situationist International is

very important within post-left anarchist thought. [38].

Other thinkers outsiede anarchism that have taken relevance in

post-left anarchy writings include Charles Fourier, the Frankfurt School, and antropologists such

as Marshall Sahlins.

See also

References

Further reading

External links

General archives

and links

Magazines

Individual writers

archive

Max

Stirner

From Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

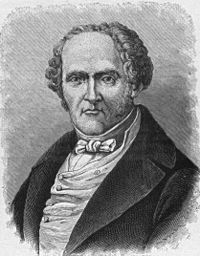

| Johann

Kaspar Schmidt |

Max Stirner, as portrayed by Friedrich Engels |

| Full name |

Johann Kaspar Schmidt |

| Born |

October 25, 1806

Bayreuth,

Bavaria |

| Died |

June 26, 1856 (aged 49)

Berlin,

Prussia

|

| Era |

19th-century

philosophy |

| Region |

Western Philosophy |

| School |

Categorised historically as a Young Hegelian.

Precursor to Existentialism, individualist feminism, Nihilism,

Individualist anarchism, Post-Modernism, Post-structuralism. |

| Main interests |

Ethics, Politics,

Property,

Value theory |

| Notable ideas |

Egoist anarchism |

|

|

Frank Brand, Steven T. Byington, Friedrich Engels, Karl

Marx, Saul Newman, Friedrich Nietzsche, Benjamin R. Tucker,

John Henry Mackay, Ernst Jünger, Rudolf Steiner, Emile Armand, Albert

Camus, Hakim Bey, Renzo Novatore, Adolf

Brand, Biófilo Panclasta,

Emma Goldman, Bob

Black, Miguel Gimenez

Igualada, Wolfi Landstreicher

|

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (October 25,

1806 – June 26, 1856), better known as Max Stirner (the nom de plume he adopted from a schoolyard

nickname he had acquired as a child because of his high brow, in German 'Stirn'), was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary

fathers of nihilism, existentialism, post-modernism and anarchism,

especially of individualist anarchism. Stirner's

main work is The Ego and Its Own, also known as

The Ego and His Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum in

German, which translates literally as The Only One and his Property).

This work was first published in 1844 in Leipzig,

and has since appeared in numerous editions and translations.

Biography

Max Stirner's birthplace in Bayreuth

Stirner was born in Bayreuth,

Bavaria.

What little is known of his life is mostly due to the Scottish

born German

writer John Henry Mackay, who wrote a biography

of Stirner (Max Stirner - sein Leben und sein Werk), published

in German in 1898 (enlarged 1910, 1914), and translated into English in 2005.

Stirner was the only child of Albert

Christian Heinrich Schmidt

(1769–1807) and Sophia Elenora Reinlein (1778–1839). His father died of

tuberculosis

on the April 19, 1807 at the age of 37. [2]

In 1809 his mother remarried to Heinrich Ballerstedt, a pharmacist,

and settled in West Prussian Kulm (now Chełmno,

Poland).

When Stirner turned 20, he attended the University of Berlin,[2]

where he studied Philology, Philosophy

and Theology.

He attended the lectures of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel,

who was to become a source of inspiration for his thinking.[3]

While in Berlin

in 1841, Stirner participated in discussions with a group of young

philosophers called "Die Freien" ("The Free"), and whom historians

have subsequently categorized as the Young Hegelians. Some of the best known

names in 19th century literature and philosophy were members of this

discussion group, including Bruno

Bauer, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Ludwig Feuerbach, and

Arnold

Ruge. While some of the Young Hegelians were eager subscribers to

Hegel's dialectical method, and

attempted to apply dialectical approaches to Hegel's conclusions, the left wing members of the group broke with

Hegel. Feuerbach and Bauer led this charge.

Frequently the debates would take place

at Hippel's, a wine bar in Friedrichstraße, attended by, among

others, the young Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels,

at that time still adherents of Feuerbach. Stirner met Engels many

times and Engels even recalled that they were "great friends",[4]

but it is still unclear whether Marx and Stirner ever met. It does not

appear that Stirner contributed much to the discussions but was a

faithful member of the club and an attentive listener. [5]

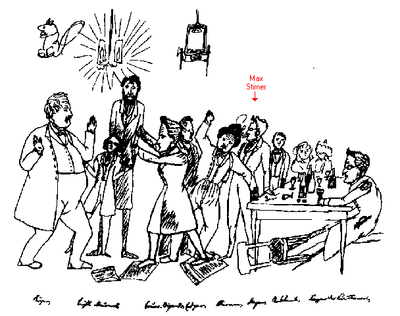

The most-often reproduced portrait of

Stirner is a cartoon by

Engels, drawn 40 years later from memory on the request of Stirner's

biographer, John Henry Mackay.

Stirner worked as a schoolteacher in a

gymnasium for young girls owned by Madame Gropius [6]

when he wrote his major work, The Ego and Its Own, which in part

is a polemic against the leading Young Hegelians

Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer, but also against communists such as Wilhelm Weitling and the anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

He resigned from his teaching position in anticipation of the

controversy arising from his major work's publication in October 1844.

Stirner married twice; his first wife was

a household servant, with

whom he fell in love at an early age. Soon after their marriage, she

died due to complications with pregnancy

in 1838. In 1843 he married Marie Dähnhardt, an intellectual

associated with Die Freien. They divorced

in 1846. The Ego and Its Own was dedicated "to my sweetheart

Marie Dähnhardt". Marie later converted to Catholicism and

died in 1902 in London.

Stirner planned and financed (with Marie's inheritance) an attempt by

some Young Hegelians to own and operate a milk-shop on co-operative

principles. This enterprise failed partly because the dairy farmers

were suspicious of these well-dressed intellectuals. The milk shop was

also so well decorated that most of the potential customers felt too

poorly dressed to buy their milk there.

After The Ego and Its Own,

Stirner wrote Stirner's Critics and translated Adam

Smith's The Wealth of Nations and Jean-Baptiste Say's Traite

d'Economie Politique into German, to little financial gain. He also

wrote a compilation of texts titled History of Reaction

in 1852. Stirner died in 1856 in Berlin from an infected insect bite;

it is said that Bruno Bauer was the only Young Hegelian present at his

funeral, which was held at the Friedhof II der

Sophiengemeinde Berlin.

Philosophy

Caricature of Max Stirner taken from a sketch by Friedrich Engels (1820

- 1895) of the meetings of "Die Freien".

Stirner's claim that the state is an

illegitimate institution has made him an influence upon the anarchist tradition; his thought is often seen

as a form of individualist anarchism. Stirner

however does not identify himself as an anarchist, and includes

anarchists among the parties subject to his criticism.

Stirner mocks revolution

in the traditional sense as tacitly statist.

David Leopold's

conclusion (in his introduction to the Cambridge University Press

edition) is that Stirner "...saw humankind as 'fretted in dark

superstition' but denied that he sought their enlightenment and

welfare" (Ibidem, p. xxxii).

As with the Classical

Skeptics, Stirner's method of self-liberation is opposed to faith

or belief; life is free from "dogmatic presuppositions" [7]

or any "fixed standpoint". [8]

It is not merely Christian dogma but

also a variety of European atheist ideologies that are condemned as

crypto-Christian for putting ideas in an equivalent

role.

What Stirner proposes is not that

concepts should rule people, but

that people should rule concepts. The denial of absolute truth is

rooted in Stirner's the "nothingness" of the self. Stirner presents a

detached life of non-dogmatic, open-minded engagement with the world

"as it is" (unpolluted by "faith", Christian or humanist),

coupled with the awareness that there is no soul, no personal essence

of any kind.

Because I cannot grasp the moon, is it therefore sacred to me, an

Astarte? If I could only grasp you, I surely would, and, if I could

only find a means to get up to you, you shall not frighten me! You

inapprehensible one, you shall remain inapprehensible to me only until

I have acquired the might for apprehension and call you my own;

I do not give myself up before you, but only bide my time. Even if for

the present I put up with my inability to touch you, I yet remember it

against you.

– Max Stirner, The Ego and

Its Own

Hegel's influence

Scholars such as Karl Löwith and Lawrence Stepelevich have argued that

Hegel was a major influence on The Ego and Its Own.[citation needed]

Stepelevich argues that while The Ego and its Own

evidently has an "un-Hegelian structure and tone to the work as a

whole", as well as being fundamentally hostile to Hegel's conclusions

about the self and the world, this does not mean that Hegel had no

effect on Stirner.

To go beyond and against Hegel in true

dialectical fashion is in

some way continuing Hegel's project, and Stepelevich argues that this

effort of Stirner's is, in fact, a completion of Hegel's project[citation needed].

Stepelevich concludes his argument referring to Jean Hyppolite, who in summing up the

intention of Hegel's Phenomenology, stated: "The history of the

world is finished; all that is needed is for the specific individual to

rediscover it in himself."

Works

The

False Principle of our Education

In 1842 Das unwahre Prinzip unserer

Erziehung (The False Principle of

our Education) or Humanism and Realism, was published

in Rheinische Zeitung, which was edited by

Marx at the time.[9]

Written as a reaction to Otto

Friedrich Theodor Heinsius' treatise Humanism vs. Realism.

Stirner explains that education in either the classical humanist method

or the practical realist method still lacks true value. Education is

fulfilled in aiding the individual in becoming an individual.

Art and Religion

Art and Religion was also

Published in Rheinische Zeitung in 1842 while Marx

was editor. It addresses Bauer and his publication against Hegel called

Hegel's doctrine of religion and art judged from the standpoint of

faith.

The Ego and Its Own

Stirner's main work is The Ego and Its Own

(org. 'Der Einzige und sein Eigentum'; according to the contemporary

German spelling 'Der Einzige und sein Eigenthum'), which appeared in Leipzig

in 1845, with as year of publication mentioned "1844". In The Ego and Its Own, Stirner

launches a radical anti-authoritarian

and individualist critique

of contemporary Prussian

society, and modern western society as such. He offers an approach to

human existence which depicts the self as a creative non-entity, beyond

language and reality.

The book proclaims that all religions and

ideologies rest on empty

concepts. The same holds true for society's institutions, that claim

authority over the individual, be it the state, legislation, the

church, or the systems of education such as Universities.

Stirner's argument explores and extends

the limits of Hegelian

criticism, aiming his critique especially at those of his

contemporaries, particularly Ludwig Feuerbach. And popular ideologies,

including nationalism, statism,

liberalism,

socialism,

communism

and humanism.

In the time of spirits thoughts grew till they overtopped my head,

whose offspring they yet were; they hovered about me and convulsed me

like fever-phantasies — an awful power. The thoughts had become

corporeal on their own account, were ghosts, e. g. God, Emperor, Pope,

Fatherland, etc. If I destroy their corporeity, then I take them back

into mine, and say: "I alone am corporeal." And now I take the world as

what it is to me, as mine, as my property; I refer all to myself.

– Max Stirner, The Ego and Its Own, p 15.

Stirner's Critics

Recensenten Stirners (Stirner's

Critics) was published in September 1845 in Wigands

Vierteljahrsschrift. It is a response to three critical reviews of The

Ego and its Own by Moses Hess in Die letzten Philosophen (The

Last Philosophers), by a certain „Szeliga“ in an article in the

journal Norddeutsche Blätter, and by Feuerbach anonymously

in an article called Über 'Das Wesen des Christentums' in

Beziehung auf Stirners 'Der Einzige und sein Eigentum' (On 'The

Essence of Christianity' in Relation to Stirner's 'The Ego and its Own'

) in Wigands Vierteljahrsschrift.

History of Reaction

Geschichte der Reaction (History

of Reaction) was published in two volumes in 1851 by Allgemeine

Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and immediately banned in Austria.[2]

It was written in the context of the recent 1848 revolutions in

German states

and is mainly a collection of the works of others selected and

translated by Stirner. The introduction and some additional passages

were Stirner's work. Edmund

Burke and Auguste Comte are quoted to show two

opposing views of revolution.

Critical reception

Stirner's work did not go unnoticed among

his contemporaries. Stirner's attacks on ideology — in particular

Feuerbach's humanism — forced Feuerbach into print. Moses

Hess (at that time close to Marx) and Szeliga (pseudonym of Franz

Zychlin von Zychlinski, an adherent of Bruno Bauer) also replied to

Stirner. Stirner answered the criticism in a German periodical, in the

article Stirner's Critics (org. Recensenten Stirners,

September 1845), which clarifies several points of interest to readers

of the book—especially in relation to Feuerbach.

While The German Ideology so assured The

Ego and Its Own a place of curious interest among Marxist

readers, Marx's ridicule of Stirner has played a significant role in

the subsequent marginalization of Stirner's work, in popular and

academic discourse.

Influence

While Der Einzige was a critical

success and attracted much

reaction from famous philosophers after publication, it was out of

print and the notoriety it had provoked had faded many years before

Stirner's death.[10]

Stirner had a destructive impact on left-Hegelianism,

though his philosophy was a significant

influence on Marx and his magnum opus became a founding text of individualist anarchism.[10]

Edmund Husserl once warned a small audience

about the "seducing power" of Der Einzige, but never mentioned

it in his writing.[11]

As the art critic and Stirner admirer Herbert

Read observed, the book has remained "stuck in the gizzard" of

Western culture since it first appeared. [12]

Many thinkers have read, and been

affected by The Ego and Its Own in their youth

including Rudolf Steiner, Gustav Landauer, Victor

Serge[13],

Carl

Schmitt and Jürgen Habermas. Few openly admit any

influence on their own thinking. [14]

Ernst Jünger's book Eumeswil,

had the character of the "Anarch", based on Stirner's

"Einzige." [15]

Several other authors, philosophers and artists have cited, quoted or

otherwise referred to Max Stirner. They include Albert

Camus in The Rebel (the section on Stirner is

omitted from the majority of English editions including Penguin's) , Benjamin Tucker, James

Huneker, [16]

Dora

Marsden, Renzo Novatore, Emma

Goldman,[17]

Georg Brandes, John Cowper Powys,[18]

Martin

Buber, [19],Sidney

Hook[20],

Robert Anton Wilson, Italian individualist anarchist Frank Brand, Russian-American

philosopher Ayn Rand,[21]

the notorious antiartist Marcel Duchamp, several writers of the Situationist International, and

Max

Ernst, who titled a 1925 painting L'unique et sa

propriété. Years before rising to power, Benito Mussolini was inspired by Stirner,

and made several references to him in his newspaper articles. The

similarities in style between The Ego and Its Own and Oscar

Wilde's The Soul

of Man Under Socialism have caused some historians to speculate

that Wilde (who could read German) was familiar with the book.[22]

Since its appearance in 1844, The Ego

and Its Own has seen

periodic revivals of popular, political and academic interest, based

around widely divergent translations and interpretations — some

psychological, others political in their emphasis. Today, many ideas

associated with post-left anarchy's criticism of

ideology and uncompromising individualism

are clearly related to Stirner's. He has also been regarded as

pioneering individualist feminism, since his

objection to any absolute concept also clearly counts gender

roles as "spooks". His ideas were also adopted by post-anarchism, with Saul

Newman largely in agreement with many of Stirner's criticisms of classical anarchism,

including his rejection of revolution and essentialism.

Marx and Engels

Engels commented on Stirner in poetry at

the time of Die Freien:

Look at Stirner, look at him, the peaceful enemy of all constraint.

For the moment, he is still drinking beer,

Soon he will be drinking blood as though it were water.

When others cry savagely "down with the kings"

Stirner immediately supplements "down with the laws also."

Stirner full of dignity proclaims;

You bend your willpower and you dare to call yourselves free.

You become accustomed to slavery

Down with dogmatism, down with law.[23]

He once even recalled at how they were

"great friends (Duzbrüder)".[4]

In November 1844, Engels wrote a letter to Marx. He reported first on a

visit to Moses Hess in Cologne, and then went on to note that during this

visit Hess had given him a press copy of a new book by Max Stirner, Der

Einzige und Sein Eigenthum. In his letter to Marx, Engels promised

to send a copy of Der Einzige

to him, for it certainly deserved their attention, as Stirner: "had

obviously, among the 'Free Ones', the most talent, independence and

diligence".[4]

To begin with Engels was enthusiastic about the book, and expressed his

opinions freely in letters to Marx:

But what is true in his principle, we, too, must accept. And what

is

true is that before we can be active in any cause we must make it our

own, egoistic

cause-and that in this sense, quite aside from any material

expectations, we are communists in virtue of our egoism, that out of

egoism we want to be human beings and not merely individuals."[24]

Later, Marx and Engels wrote a major

criticism of Stirner's work.

The number of pages Marx and Engels devote to attacking Stirner in (the

unexpurgated text of) The German Ideology exceeds the

total of Stirner's written works. As Isaiah

Berlin has described it, Stirner "is pursued through five hundred

pages of heavy-handed mockery and insult".[25]

The book was written in 1845–1846, but not published until 1932. Marx's

lengthy, ferocious polemic against Stirner has

since been considered an important turning point in Marx's intellectual

development from idealism to materialism.

Stirner and

post-structuralism

Saul

Newman calls Stirner a proto-poststructuralist who on the one hand

had essentially anticipated modern post-structuralists such as Foucault,

Lacan, Deleuze, and Derrida, but on the other had already

transcended them, thus providing what they were unable to: a ground for

a non-essentialist

critique of present liberal capitalist society. This is particularly

evident in Stirner's identification of the self with a "creative

nothing", a thing that cannot be bound by ideology, inaccessible to

representation in language.

Possible

influence on Nietzsche

The ideas of Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche

have often been compared, and many authors have discussed apparent

similarities in their writings, sometimes raising the question of

influence.[26]

In Germany, during the early years of Nietzsche's emergence as a

well-known figure, the only thinker discussed in connection with his

ideas more often than Stirner was Schopenhauer.[27]

It is certain that Nietzsche read about Stirner's most important book The Ego and Its Own (Der

Einzige und sein Eigentum), which was mentioned in Lange's History of Materialism

and Eduard von Hartmann's

Philosophy of the Unconscious, both of which Nietzsche knew well.[28]

However, there is no indication that he actually read it, as no mention

of Stirner is known to exist anywhere in Nietzsche's publications,

papers or correspondence.[29]

Recently a biographical discovery made it probable that Nietzsche had

encountered Stirner's ideas before he read Hartmann and Lange, in

October 1865, when he met with Eduard Mushacke, an old friend of

Stirner's during the 1840s. [30]

And yet as soon as Nietzsche's work began

to reach a wider audience

the question of whether or not he owed a debt of influence to Stirner

was raised. As early as 1891 (while Nietzsche was still alive, though

incapacitated by mental illness) Eduard von Hartmann went so far as to

suggest that he had plagiarized Stirner.[31]

By the turn of the century the belief that Nietzsche had been

influenced by Stirner was so widespread that it became something of a

commonplace, at least in Germany, prompting one observer to note in

1907 "Stirner's influence in modern Germany has assumed astonishing

proportions, and moves in general parallel with that of Nietzsche. The

two thinkers are regarded as exponents of essentially the same

philosophy."[32]

Nevertheless, from the very beginning of

what was characterized as "great debate"[33]

regarding Stirner's possible positive influence on Nietzsche, serious

problems with the idea were noted.[34]

By the middle of the 20th century, if Stirner was mentioned at all in

works on Nietzsche, the idea of influence was often dismissed outright

or abandoned as unanswerable.[35]

But the idea that Nietzsche was

influenced in some way by Stirner

continues to attract a significant minority, perhaps because it seems

necessary to explain in some reasonable fashion the often-noted (though

arguably superficial) similarities in their writings.[36]

In any case, the most significant problems with the theory of possible

Stirner influence on Nietzsche are not limited to the difficulty in

establishing whether the one man knew of or read the other. They also

consist in establishing precisely how and why Stirner in particular

might have been a meaningful influence on a man as widely read as

Nietzsche.[37]

Rudolf Steiner

The individualist-anarchist orientation

of Rudolf Steiner's

early philosophy – before he turned to theosophy around 1900 – has

strong parallels to, and was admittedly influenced by Stirner's

conception of the ego, for which Steiner claimed to have provided a

philosophical foundation.[38]

Anarchism

Stirner´s philosophy is important

in anarchism. Usually Stirner within anarchism is associated with individualist anarchism but he

found admiration in mainstream social anarchists

such as anarcha-feminists Emma

Goldman and Federica Montseny (both also admired Friedrich Nietzsche). As such in european

individualist anarchism he influenced its main proponents after him

such as Emile Armand, Han

Ryner, Renzo Novatore, John Henry Mackay, Miguel Giménez Igualada and

Lev

Chernyi.

In american

individualist anarchism he found adherence in Benjamin Tucker and his magazine Liberty

while these abandoned natural rights positions for egoism[39].

"Several

periodicals were undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's

presentation of egoism. They included: I published by C.L. Swartz,

edited by W.E. Gordak and J.W. Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); The

Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton.

Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der

Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand, and The Eagle and The Serpent, issued

from London. The latter, the most prominent English-language egoist

journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle “A Journal

of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology”"[39].

Other american egoist anarchists

around the early 20th century include James L. Walker, George Schumm

and John Beverley Robinson,

Steven T. Byington and E.H. Fulton[39].

In the United Kingdom Herbert

Read was influenced by Stirner. Later in the 1960s Daniel Guerin in Anarchism: From Theory to

Practice

says that Stirner "rehabilitated the individual at a time when the

philosophical field was dominated by Hegelian anti-individualism and

most reformers in the social field had been led by the misdeeds of

bourgeois egotism to stress its opposite" and pointed to "the boldness

and scope of his thought."[40]

In the seventies an american situationist collective called For Ourselves

published a book called The

Right To Be Greedy: Theses On The Practical Necessity Of Demanding

Everything in which they advocate a "communist egoism" basing

themselves on Stirner[41].

Later in the USA emerged the tendency of post-left anarchy which was influenced

profundly by Stirner in aspects such as the critique of ideology. Jason

McQuinn

says that "when I (and other anti-ideological anarchists) criticize

ideology, it is always from a specifically critical, anarchist

perspective rooted in both the skeptical, individualist-anarchist

philosophy of Max Stirner[42].

Also Bob

Black and Feral Faun/Wolfi Landstreicher strongly adhere to

stirnerist egoism. In the hybrid of post-structuralism and Anarchism called

post-anarchism Saul

Newman has written on Stirner and his similarities to

post-structuralism. Insurrectionary anarchism also

has an important relationship with Stirner as can be seen in the work

of Wolfi Landstreicher and Alfredo

Bonanno who has also written on him in works such as Max Stirner

and "Max Stirner und der Anarchismus"[43]

Twenty years after the appearance of

Stirner's book, the author Friedrich Albert Lange wrote the

following:

Stirner went so far in his notorious work, 'Der Einzige und Sein

Eigenthum' (1845), as to reject all moral ideas. Everything that in any

way, whether it be external force, belief, or mere idea, places itself

above the individual and his caprice, Stirner rejects as a hateful

limitation of himself. What a pity that to this book — the extremest

that we know anywhere — a second positive part was not added. It would

have been easier than in the case of Schelling's

philosophy; for out of the unlimited Ego

I can again beget every kind of Idealism

as my will and my idea.

Stirner lays so much stress upon the will, in fact, that it appears as

the root force of human nature. It may remind us of Schopenhauer.

– History of

Materialism, ii. 256 (1865)

Some people think that, in a sense, a

"second positive part" was soon to be added, though not by Stirner, but

by Friedrich Nietzsche. The

relationship between Nietzsche and Stirner seems to be much more

complicated. [44]

According to George J. Stack's Lange and Nietzsche[45],

Nietzsche read Lange's History of Materialism "again and again"

and was therefore very familiar with the passage regarding Stirner.

Notes

- ^

The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, volume 8, The Macmillan Company and The

Free Press, New York 1967.

- ^ a

b

c

John Henry Mackay: Max Stirner --

Sein Leben und sein Werk p.28

- ^ The

Encyclopedia of Philosophy, volume 8, The Macmillan Company and The

Free Press, New York 1967.

- ^ a

b

c

Lawrence L Stepelevich, The revival of Max Stirner

- ^

Gide, Charles & Rist, Charles. A History of Economic Doctrines from

the Time of the Physiocrats to the Present Day. Harrap 1956, p. 612

- ^

The Encyclopedia of Philsosophy, volume 8, The Macmillan Company and

The Free Press, New York 1967

- ^

p. 135, 309

- ^

p. 295

- ^

Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, The Macmillan company Press, New York, 1967

- ^ a

b

"Max Stirner" article in the Stanford Encyclopedia of

Philosophy

- ^ Max Stirner, a durable dissident

- in a nutshell

- ^

Quoted in Read’s book, “The Contrary Experience”, Faber and Faber, 1963.

- ^

See Memoirs of a revolutionary, 1901-1941 by Victor Serge. Publisher

Oxford U.P., 1967

- ^

See Bernd A. Laska: Ein dauerhafter Dissident. Nürnberg:

LSR-Verlag 1996 (online)

- ^

See Bernd A. Laska: Katechon und Anarch. Nürnberg:

LSR-Verlag 1997 (online)

- ^

Huneker's book Egoists, a Book of Supermen (1909)contains an

essay on Stirner.

- ^

See Goldman, Anarchism and Other Essays, p. 50.

- ^ World of books - Telegraph

- ^ Between

Man and Man by Martin Buber,Beacon Press, 1955.

- ^

From Hegel to Marx by Sidney Hook, London, 1936.

- ^

See "The Letters of Ayn Rand," pg. 176, Dutton, 1995.

- ^ David

Goodway, Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow, Liverpool

University Press, 2006 (pg.75).

- ^

Henri Arvon, Aux sources de 1'existentialisme Max Stirner (Paris,

1954), p. 14

- ^

Zwischen 18 and 25, pp. 237-238.

- ^

I. Berlin, Karl Marx (New York, 1963), 143.

- ^

Albert Levy, Stirner and Nietzsche, Paris, 1904; Robert

Schellwien, Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche, 1892; H.L.

Mencken, The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche,

1908; K. Löwith, From Hegel To Nietzsche New York, 1964, p187;

R.A.

Nicholls, "Beginnings of the Nietzsche Vogue in Germany", in Modern

Philology,

Vol. 56, No. 1, Aug., 1958, pp. 24-37; T. A. Riley, "Anti-Statism in

German Literature, as Exemplified by the Work of John Henry Mackay", in

PMLA, Vol. 62, No. 3, Sep., 1947, pp. 828-843; Seth Taylor, Left

Wing Nietzscheans, The Politics of German Expressionism 1910-1920,

p144, 1990, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/New York; Gilles Deleuze, Nietzsche

et la Philosophy, Presses Universitaires de France, 1962; R. C.

Solomon & K. M. Higgins, The Age of German Idealism, p300,

Routledge, 1993

- ^

While discussion of possible influence has never ceased entirely, the

period of most intense discussion occurred between 1892 and 1900 in the

German-speaking world. During this time, the most comprehensive account

of Nietzsche's reception in the German language, the 4 volume work of

Richard Frank Krummel: Nietzsche und der deutsche Geist

indicates 83 entries discussing Stirner and Nietzsche. The only thinker

more frequently discussed in connection with Nietzsche during this time

is Schopenhauer, with about twice the number of entries. Discussion

steadily declines thereafter, but is still significant. Nietzsche and

Stirner show 58 entries between 1901 and 1918. From 1919 to 1945 there

are 28 entries regarding Nietzsche and Stirner.

- ^

"Apart from the information which can be gained from the annotations,

the library (and the books Nietzsche read) shows us the extent, and the

bias, of Nietzsche's knowledge of many fields, such as evolution and

cosmology. Still more obvious, the library shows us the extent and the

bias of Nietzsche's knowledge about many persons to whom he so often

refers with ad hominem statements in his published works. This includes

not only such important figures a Mill, Kant, and Pascal but also such

minor ones (for Nietzsche) as Max Stirner and William James who are

both discussed in books Nietzsche read." T. H. Brobjer, "Nietzsche's

Reading and Private Library", 1885-1889, in Journal of the History

of Ideas,

Vol. 58, No. 4, Oct., 1997, pp. 663-693; Stack believes it is doubtful

that Nietzsche read Stirner, but notes "he was familiar with the

summary of his theory he found in Lange's history." George J. Stack, Lange

and Nietzsche, Walter de Gruyter, 1983, p 276

- ^

Albert Levy, Stirner and Nietzsche, Paris, 1904

- ^ Bernd A. Laska: Nietzsche's

initial crisis. In: Germanic Notes and Reviews, vol. 33, n. 2,

fall/Herbst 2002, pp. 109-133

- ^

Eduard von Hartmann, Nietzsches "neue Moral", in Preussische

Jahrbücher, 67. Jg., Heft 5, Mai 1891, S. 501-521; augmented

version with more express reproach of plagiarism in: Ethische

Studien, Leipzig, Haacke 1898, pp. 34-69

- ^

This author believes that one should be careful in comparing the two

men. However, he notes: "It is this intensive nuance of individualism

that appeared to point from Nietzsche to Max Stirner, the author of the

remarkable work Der Einzige und sein Eigentum. Stirner's

influence in modern Germany has assumed astonishing proportions, and

moves in general parallel with that of Nietzsche. The two thinkers are

regarded as exponents of essentially the same philosophy." O. Ewald,

"German Philosophy in 1907", in The Philosophical Review, Vol.

17, No. 4, Jul., 1908, pp. 400-426

- ^

[in the last years of the 19th century] "The question of whether

Nietzsche had read Stirner was the subject of great debate" R.A.

Nicholls, "Beginnings of the Nietzsche Vogue in Germany", in Modern

Philology, Vol. 56, No. 1, Aug., 1958, pp. 29-30

- ^

Levy pointed out in 1904 that the similarities in the writing of the

two men appeared superficial. Albert Levy, Stirner and Nietzsche,

Paris, 1904

- ^

R.A. Nicholls, "Beginnings of the Nietzsche Vogue in Germany", in Modern

Philology, Vol. 56, No. 1, Aug., 1958, pp. 24-37

- ^

"Stirner, like Nietzsche, who was clearly influenced by him, has been

interpreted in many different ways", Saul

Newman, From Bakunin to Lacan: Anti-authoritarianism and

the Dislocation of Power,

Lexington Books, 2001, p 56; "We do not even know for sure that

Nietzsche had read Stirner. Yet, the similarities are too striking to

be explained away." R. A. Samek, The Meta Phenomenon, p70, New

York, 1981; Tom Goyens, (referring to Stirner's book The Ego and His

Own) "The book influenced Friedrich Nietzsche, and even Marx and Engels

devoted some attention to it." T. Goyens, Beer and Revolution: The

German Anarchist Movement In New York City, p197, Illinois, 2007

- ^

"We have every reason to suppose that Nietzsche had a profound

knowledge of the Hegelian movement, from Hegel to Stirner himself. The

philosophical learning of an author is not assessed by the number of

quotations, nor by the always fanciful and conjectural check lists of

libraries, but by the apologetic or polemical directions of his work

itself." Gilles Deleuze (translated by Hugh Tomlinson), Nietzsche and Philosophy,

1962 (2006 reprint, pp. 153-154)

- ^

Guido Giacomo Preparata, "Perishable Money in a Threefold Commenwealth:

Rudolf Steiner and the Social Economics of an Anarchist Utopia". Review

of Radical Economics 38/4 (Fall 2006). Pp. 619-648

- ^ a

b

c

"Only the influence of the German philosopher of egoism, Max Stirner

(nè Johann Kaspar Schmidt, 1806–1856), as expressed through The

Ego and

His Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum) compared with that of Proudhon.

In adopting Stirnerite egoism (1886), Tucker rejected natural rights

which had long been considered the foundation of libertarianism. This

rejection galvanized the movement into fierce debates, with the natural

rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism

itself. So bitter was the conflict that a number of natural rights

proponents withdrew from the pages of Liberty in protest even though

they had hitherto been among its frequent contributors. Thereafter,

Liberty championed egoism although its general content did not change

significantly."Wendy Mcelroy. "Benjamin Tucker,

Individualism, & Liberty: Not the Daughter but the Mother of Order"

- ^

Daniel Guerin,Anarchism:

From Theory to Practice

- ^ Four Ourselves, The Right To Be

Greedy: Theses On The Practical Necessity Of Demanding Everything

- ^

"What is Ideology?" by Jason

McQuinn

- ^ BONANNO, Alfredo Maria

- ^

See Bernd A. Laska: Nietzsche's

initial crisis. In: Germanic Notes and Reviews, vol. 33, n. 2,

fall/Herbst 2002, pp. 109-133

- ^

George J. Stack, Lange and Nietzsche, Walter de Gruyter,

Berlin, New York, 1983, p. 12, ISBN 3-11-00866-5

See also

References

- Stirner, Max: Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (1845

[October 1844]). Stuttgart: Reclam-Verlag, 1972ff; engl. trans. The Ego and Its Own (1907), ed. David Leopold,

Cambridge/ New York: CUP 1995

- Stirner, Max: "Recensenten Stirners" (Sept. 1845). In: Parerga,

Kritiken, Repliken, Bernd A. Laska, ed., Nürnberg: LSR-Verlag,

1986; engl. trans. Stirner's Critics (abridged), see below

- Stack, George J., Lange and Nietzsche, Berlin, New York:

Walter de Gruyter, 1983, ISBN 3-11-00866-5

Further reading

- Max Stirners 'Der Einzige und sein Eigentum' im Spiegel der

zeitgenössischen deutschen Kritik. Eine Textauswahl (1844-1856).

Hg.

Kurt W. Fleming. Leipzig: Verlag Max-Stirner-Archiv 2001

- Arvon, Henri, Aux Sources de l'existentialisme, Paris: P.U.F. 1954

- De Ridder, Widukind, "Max Stirner, Hegel and the Young Hegelians:

A reassessment". In: History of European Ideas, 2008, 285-297.

- Essbach, Wolfgang, Gegenzüge. Der Materialismus des Selbst.

Eine

Studie über die Kontroverse zwischen Max Stirner und Karl Marx.

Frankfurt: Materialis 1982

- Helms, Hans G, Die Ideologie der anonymen Gesellschaft. Max

Stirner

‘Einziger’ und der Fortschritt des demokratischen Selbstbewusstseins

vom Vormärz bis zur Bundesrepublik, Köln: Du Mont Schauberg,

1966

- Koch, Andrew M., “Max Stirner: The Last Hegelian or the First

Poststructuralist”. In: Anarchist Studies, vol. 5 (1997) pp. 95–108

- Laska, Bernd A., Ein dauerhafter Dissident. Eine

Wirkungsgeschichte des Einzigen, Nürnberg: LSR-Verlag 1996 (TOC, index)

- Laska, Bernd A., Ein heimlicher Hit. Editionsgeschichte des

„Einzigen“. Nürnberg: LSR-Verlag 1994 (abstract)

- Marshall, Peter H. "Max Stirner"

in "Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism "(London:

HarperCollins, 1992).

- Newman, Saul, Power and Politics in

Poststructural Thought. London and New York: Routledge 2005

- Stepelevich, Lawrence S., Max Stirner As Hegelian. In: Journal of

the History of Ideas, Vol. 46, nr. 4, pp. 597–614

- Stepelevich, Lawrence S., Ein Menschenleben. Hegel and Stirner”.

In: Moggach, Douglas (ed.): The New Hegelians. Philosophy and Politics

in the Hegelian School. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006,

pp. 166–176

- Paterson, R.W.K., The Nihilistic Egoist: Max Stirner, Oxford:

Oxford University Press 1971

External links

General

Relationship

with other philosophers

Texts

Anarchy:

A Journal of Desire Armed

From Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed

is a North American anarchist

magazine, and is one of the most popular anarchist publications in

North America. It could be described as a general interest and

critical, non-ideological anarchist journal. It was founded by members

of the Columbia Anarchist League of Columbia, Missouri, and continued to be

published there for nearly fifteen years, eventually under the sole

editorial control of Jason

McQuinn

(who initially used the pseudonym "Lev Chernyi"), before briefly moving

to New York City in 1995 to be published by members of the Autonomedia

collective. The demise of independent distributor Fine Print

nearly killed the magazine, necessitating its return to the Columbia

collective after just two issues. It remained in Columbia from 1997 to

2006. As of 2006[update] it is

published bi-annually by a group based in Berkeley, California.[1][2]

The magazine accepts no advertising.

It has serially published two book-length works, The

Papalagi and Raoul Vaneigem's The Revolution of Everyday Life.

Perspective and

contributors

The magazine is noted for spearheading

the Post-left anarchy critique ("beyond the

confines of ideology"), as articulated by such writers as Lawrence Jarach, John

Zerzan, Bob Black, and Wolfi Landstreicher (formerly Feral

Faun/Feral Ranter among other noms de plume). Zerzan is now best known as

the foremost proponent of anarcho-primitivism. The magazine has

been open to publishing the primitivists, which has caused leftist

critics and academics like Ruth

Kinna (editor of Anarchist Studies)

to classify the magazine as primitivist, but McQuinn, Jarach and others

have published critiques of primitivism there. Bob Black is best known

for "The Abolition of Work" (1985), a

widely reprinted and translated essay (first widely circulated, in

fact, as an insert in Anarchy in 1986[citation needed]), but

for Anarchy he has mainly contributed critiques of leftists and

anarcho-leftists such as Ward Churchill, Fred Woodworth, Chaz

Bufe, Murray Bookchin, the Platformists and most recently AK Press.

Wolfi Landstreicher now writes from the "insurrectionalist"

perspective of Renzo Novatore and Alfredo Bonanno (he

has translated both) which combines a sympathy for generalized,

spontaneous, unmediated uprising with the egoism of Max

Stirner.

References

External links

Green

Anarchy

From Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

This article is about

the Oregon magazine. For the U.K. magazine, see

Green Anarchist.

Green Anarchy is a magazine

published by a collective located in Eugene, Oregon. The magazine's focus is on primitivism, post-left anarchy, radical environmentalism,

anarchist resistance, indigenous resistance, earth and animal

liberation, anti-capitalism and supporting political prisoners.

It has a circulation of 8,000.[1]

The subtitle of the magazine is "An

Anti-Civilization Journal of Theory and Action".

According to their web site,[2]

Green Anarchy was established in the summer of 2000 by one of

the founders of Green Anarchist, "a similar, yet more

rudimentary, publication from the United Kingdom" and "began as a basic

introduction to eco-anarchist

and radical environmental ideas, but after a year of limited success,

members of the current collective took on the project with an

enthusiastic trajectory."

Author John

Zerzan is currently one of the publication's editors.

See also

References

External links

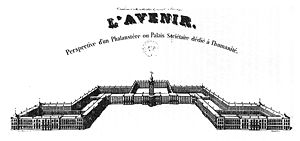

Charles

Fourier

From Wikipedia, the free

encyclopedia

This article is about

the French utopian socialist philosopher. For other people named

Fourier, see

Fourier.

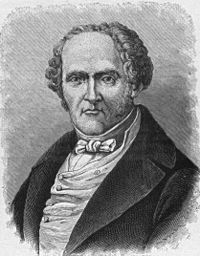

François Marie Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier

(7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French utopian socialist

and philosopher. Fourier is

credited by modern scholars with having originated the word féminisme

in 1837;[1]

as early as 1808, he had argued, in the Theory

of the Four Movements,

that the extension of the liberty of women was the general principle of

all social progress, though he disdained any attachment to a discourse

of 'equal rights'. Fourier inspired the founding of the communist community called La Reunion near present-day Dallas, Texas as

well as several other communities within the United States of

America, such as the North American Phalanx in New

Jersey and Community Place and five others in New

York State.

Biography

Fourier was born in Besançon

on April 7, 1772.[2]

Born a son of a small businessman, Fourier was more interested in

architecture than he was in his father's trade.[2]

In fact, he wanted to become an engineer, but since the local Military

Engineering School only accepted sons of noblemen, he was automatically

ineligible for it.[2]

Fourier later was grateful that he did not pursue engineering, for he

stated that it would have consumed too much of his time and taken away

from his true desire to help humanity.[3]

In July 1781 after his father’s death, Fourier received two-fifths of

his father’s estate, valued at more than 200,000 francs.[4]

This sudden wealth enabled Fourier the freedom to travel throughout

Europe at his leisure. In 1791 he moved from Besançon

to Lyon,

where he was employed by the merchant M. Bousqnet.[5]

Fourier's travels also brought him to Paris

where he worked as the head of the Office of Statistics for a few

months..[2]

Fourier was not satisfied with making journeys on behalf of others for

their commercial benefit.[6]

Having a desire to seek knowledge in everything he could, Fourier often

would change business firms as well as residences in order to explore

and experience new things. From 1791 to 1816 Fourier was employed in

the cities of Paris, Rouen, Lyon, Marseille,

and Bordeaux.[7]

As a traveling salesman and correspondence clerk, his research and

thought was time-limited: he complained of "serving the knavery of

merchants" and the stupefaction of "deceitful and degrading duties". A

modest legacy set him up as a writer. He had three main sources for his