|

James K. Galbraith

belongs to the most distinguished economists in the United States

today. In the following exclusive interview that was conducted for New

Deal 2.0 in the USA and MMNews in Germany, he talks about the financial

/ economic crisis and the phenomenon of Peak Oil, points at future

tasks and explains why he supports the Audit the Fed bill.

James

K. Galbraith, who holds the Lloyd M.

Bentsen, Jr. Chair of Government/Business Relations at the Lyndon B.

Johnson

School of Public Affairs at the University

of Texas in Austin, is the son of the legendary

economist John Kenneth Galbraith. He

is a

frequent speaker

on matters related to the financial and economic crisis and has been a

witness before

Congress on several recent occasions. Mr. Galbraith is the author of

seven

books. His two most recent books are: “Unbearable

Cost: Bush, Greenspan and the Economics of Empire” (published by

Palgrave-MacMillan in late 2006), and “The

Predator State: How Conservatives Abandoned the

Free Market and Why Liberals Should Too” (published by Free Press

in August

2008 – for more information visit: http://predatorstate.com).

Robert

B. Reich,

Professor of Public Policy, University

of California at Berkeley, wrote about “The Predator State”:

"James

Galbraith elegantly and effectively

counters the economic fundamentalism that has captured public discourse

in

recent years, and offers a cogent guide to the real political economy.

Myth-busting, far-ranging, and eye-opening."

Moreover,

Mr. Galbraith has written several

hundred scholarly and policy articles, including columns in Mother

Jones and

articles / op-ed’s in The American Prospect, the Nation, and the

Washington

Post. He studied economics as a Marshall Scholar at King's College,

Cambridge in 1974-1975 and

holds

degrees from Harvard and Yale

(Ph.D. in Economics, 1981). Later he served on the staff of the U.S.

Congress

as Executive Director of the Joint Economic Committee before joining

the

faculty of the University

of Texas in 1985. In

public life, he organized congressional oversight of the Federal

Reserve (the

Humphrey-Hawkins hearings) and worked on financial crises including the

Third World debt crisis of the 1980s. In the 1990s he

served for four years as Chief Technical Adviser for macroeconomic

reform to

the State Planning Commission of China. He was called to advise the

House of

Representatives on the TARP legislation in September 2008 and on

recovery

strategy in December of the same year. He was also invited to Congress

to give

his point of view about the “Audit the Fed” initiative of Congressman

Ron Paul

(House

Resolution 1207

Federal Reserve Transparency Act of 2009 – to see Mr. Galbraith’s

testimony on

Capitol Hill follow this link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oxAt-Un1k7I).

As an

outspoken critic of the free market

consensus, especially the

monetarist version of Milton Friedman,[i]

Mr. Galbraith argues that Keynesian economics offers a solution to the

current

financial crisis, whereas monetarist policies would deepen it.

Mr.

Galbraith’s scholarly research has focused

on the measurement and understanding of inequality in the world

economy, under

the rubric of the University

of Texas Inequality Project,

UTIP (for more information on that topic visit the web-site of UTIP at http://utip.gov.utexas.edu).

His policy

writing ranges from monetary policy to the economics of warfare, with

forays

into politics and history, especially the history of the Vietnam War.

He is a

Senior Scholar with the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, and

Chair of

the Board of Economists for Peace and Security, an international

association of

professional economists (www.epsusa.org).

His

papers on macroeconomic topics can be found on the Levy web-site at www.levy.org. An archive of his

writings can be

also found at http://www.utexas.edu/lbj/faculty/galbraith.html.

The

following exclusive interview with James K. Galbraith is a Joint

Venture between New Deal 2.0 in the USA (www.newdeal20.org)

and MMNews in Germany (www.mmnews.de).

Professor

Galbraith, in July

of 2009 you have signed an initiative of the Franklin

and Eleanor

Roosevelt Institute that wants an answer

to the question: What Caused the Crisis?[ii]

May I ask for your personal answer?

Yes, you may. (laughs.)

– The principal cause of the crisis was the dismantling

of the system of regulation and supervision in the financial sector

which had

for much of the post-war period kept the most dangerous elements of

that sector

in check. In the absence of an appropriate system of effective

supervision and

regulation, what happens is that the actors in the system, who are

intent upon

taking the greatest degree of risk -- including actors who are intent

upon

using fraudulent methods to increase their returns -- come to dominate

parts of

the system. As they do that, the general methods of assessing

performance in

the market, specifically stock-market valuations, become

counter-productive.

That is to say, they invariably reward

the worst actors, while they force more traditional actors, who are

still

respecting the old norms of conduct, into a competitively disadvantaged

position. Thus the bad actors, the fraudulent actors, and the

speculative

extremists quickly take over.

That is what happened

specifically in the

origination of mortgages in the United

States in the middle part of the last

decade. You had a transition from a traditional method of issuing

mortgages to

people who could be reasonably expected to service them, to a method of

originating mortgages that were sold off immediately, that were rated

in a way

that permitted them to be bundled and sold to fiduciaries, and where

the issuer

had no interest in whether the borrowers could pay or not. In fact, in

some

ways the lenders actively preferred people who did not intend to pay,

because

they could then inflate the value of the loan and earn a larger fee

upfront for

doing it. And in this way, not only was there a large segment of the

market

that was explicitly corrupt, but the equity value of homes all across

the

country was compromised. When these practices collapsed, so too did the

home

values not only of people who had bad mortgages, but also those for

many people

who had good mortgages, good incomes and perfectly good credit.

The result of that was

a general slump in

activity. The wealth and financial security of much of the American

middle

class disappeared. So far about a quarter of the measured wealth of the

American middle class has disappeared – about $15 trillion of $60

trillion. That’s bound to have a

fantastically traumatic effect on people’s consumption behaviour and on

their

ability to get new good credit. Even if they wish to continue to extend

the

past pattern of borrowing in order to finance activity, they can’t do

it. So, this is a very big problem. It starts

with a failure to supervise and regulate the financial system, and

flows on to

the reaction of the broader population, which is to protect their

remaining

assets, to become extremely adverse to taking ordinary business and

consumer

risks.

How much

of this

crisis is related to what you call “the

Economics of Empire” during the presidency of George W. Bush?

I think at the end of

the day that’s not the primary

factor. There was reason, good reason, to be concerned at the start of

the Iraq

War, that the war would be vastly more costly than was predicted, that

it would

be a much more difficult war than was predicted, and that it would

damage the

strength of America’s position in the world. All of that has certainly

happened. But the war itself was not a strong enough fiscal stimulus to

bring

the economy out of the recession of 2000/2001, at least not in a

decisive way,

and it’s partly for that reason that the Bush Administration 2004/2005

set

about actively encouraging the use of these credit mechanisms in the

housing

market. Out of that, they got a higher level of economic activity than

they

otherwise would have had, they avoided a period of stagnation that

otherwise

would have been worse -- was until the

whole business collapsed completely in 2007/2008.

Marshall

Auerback stated

in an interview that I had with him this:

“In all important

respects we managed to recreate the exact same conditions of 1929 and

history

repeated itself with the exact same results. Take John Kenneth

Galbraith’s The

Great Crash,[iii]

change the dates and some of the names and you’ve got the post

mortem of

our current calamity.”[iv]

Do you

agree with Mr.

Auerback?

Of course, and so does

the book-buying public

which took an enormous interest in “The

Great Crash” over the last couple of years.

So you

believe that

your father’s “The Great Crash 1929,”

which was first published in 1954, is still of relevance today?

It describes behaviour

and psychology in the

financial markets very effectively. There are a couple of important

things that

have changed. One is the existence and continued vitality of some of

the

institutions that were created in the New Deal and the Great Society,

giving us

a much larger public sector as well as a very large non-profit sector,

neither

of which existed in the 1920’s. The capacity of the public sector to

move to

run very large deficits very quickly and practically automatically, is

a saving

grace; it’s the reason that we have a 10% unemployment rate and not a

25%

unemployment rate in the wake of this crash. That’s an extremely

important and

valuable difference between now and the 1930’s.

My father he does not

give the same weight to

the element of outright fraud, back in 1929, that I would regard as a

truly

dominant factor in this crisis. There certainly was fraud in the

1920’s, there

was a great epidemic of what we would call bucket-shops in the

stock-market,

there was a lot of fraud in Florida

real-estate in the mid-1920’s. But this was overshadowed by a general

euphoria

about economic prospects. People who went into the stock-market, at

least in my

father’s depiction of this period, were doing so out of a great deal of

authentic enthusiasm. From that point of view the period resembles the

late

1990’s more than it does the middle 2000’s. During the middle 2000’s

the

economy was being propelled by predatory activity directed at a very

vulnerable

segment of the American population, people who had been renters all

their

lives, who really couldn’t afford to be moved into houses, who were

aggressively moved into them by unscrupulous lenders. The lenders

basically

pushed loans on to borrowers that the lenders knew, or who ought to

have known,

could never have been serviced in full.

In a

recent interview

for MMNews, Hans-Olaf Henkel, who was once the head of the Federation

of German

Industries as well as IBM Europe, said two things that I would like to

confront

you with because Mr. Henkel is an influential opinion-maker here in

Germany.[v]

The first thing he

said was that basically no one saw this crisis coming and that he

laughs

himself to death whenever someone says that this crisis was foreseen.

Can you

give Mr. Henkel some names in this respect? How about Dean Baker for

example?

I’ve written a long

article on not just the

individual economists, but groups of economists who saw the crisis

coming very

clearly.[vi] Dean is one certainly with a

strong claim.

Dean follows a very simple method. He

looks at critical ratios, such as the ratio of house prices to rental

rates.

When these deviated very far from their historical norms, that

generates an

expectation that they would revert. People should have been looking at

that

evidence and taking Dean’s predictions far more seriously than they

did. But on

the other hand, what Dean is pursuing is

a very simple method and couldn’t be described as a school of economic

analysis.

There are at least

three traditions in

economics that were warning about what was coming in ways which were

very

coherently related to a formal analytical program.

There is a group

associated with the Levy Economics

Institute and led by Wynne Godley,

former senior advisor to the British Treasury. This group

was working

with national balance sheets -- with the national income accounts --

and

warning very emphatically that the debt-burden of the household sector

was

unsustainable..

There are people

working in the tradition of

Hyman Minsky, who of course were trained

to expect financial instability. They were making similar points from a

substantially different conceptual basis.

And then there are

people working broadly in

the tradition of my father, who look at the structures of economic

power, and

who were warning that the supervision of the banking system was going

to cause

an epidemic of fraud. There was a group of what we call “white-collar

criminologists”, who were examining these issues, and they are

developing a new

political economy of crime.

This group had the

experience of what happened

in the Savings and Loan crisis of the 1980’s, when certain patterns of

behaviour, which are relatively standard in criminal financial

activity, were

very clearly present. These patterns re-emerged in the early 2000’s in

the

Enron, Worldcom, and Tyco scandals, and they were re-emerging again in

the

housing sector. To these people it was entirely obvious that a massive

problem

was developing.

So, Mr. Henkel needs

to read a little bit more,

He needs to broaden his definition of what constitutes economic

analysis, and

needs to recognize that the problem is precisely a group of people who

insist

that nobody outside of their very narrow circle has any insight worth

paying

attention to. That’s a preposterous position. It’s a completely

indefensible

position. It reflects fundamental narrowed-mindedness and, as I may

say,

incompetence which is really on display for anybody to see. So I do not

need to

hammer the point too hard.

The other

thing that I want to know with regard to Mr. Henkel’s statements is

this: He

said that this crisis was caused by a certain type of “do-goodism”

among

American politicians who wanted to make sure that every American

citizen would

have a home of her/his own. What do you think when you hear such a

thing?

It is an amusing

interpretation of the motives

of someone like George W. Bush, who represented one of the most

aggressively

predatory tendencies in American politics ever to reach the White

House. This

was a president who turned over regulation -- not just in finance but

in

everything he got his hands on -- to the most reactionary elements of

the

business community, to the most anti-regulation elements, so that

regulatory

structures were run down everywhere. They were run down in consumer

protection,

they were run down in worker protection, they were run down in trade,

they were

run down in ways which have significantly degraded the quality of life

in the United States.

So, to suggest that

this was some naïve

altruism on the part of that extraordinarily reactionary Republican

administration is, I must say, a view that no one who has actually

lived

through this period in the United

States would recognize.

Now, Mr. Henkel is

probably thinking about

institutions like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac which were, in fact,

private

firms. Fannie Mae had been privatized for forty years, and it had,

indeed,

become a bastion of Washington

cronyism. I think that’s fair to say. Those institutions were

drastically

mismanaged by the overpaid appointees who were running them, no doubt

about

that. Ginnie Mae, the Government National Mortgage Association, which

was not

privatized, did not have the same problems.

But the truth is: this

crisis emerged largely

first of all in the private-label mortgage sector, that is to say in

purely

private entities like Countrywide, Washington Mutual, or IndyMac. The

loans

were securitized through private banks, vetted by private ratings

agencies. The

point here was not to put people in homes. It was clear to the lenders

that the

people that they were putting in homes would not be able to stay there.

The point was

obviously to do two things. One

was to create an enormous stream of revenue for these financial firms

-- who

were in many cases friends and political supporters of the

administration.

Second, it was to create a temporary burst of economic activity

that would be to the political benefit of the

Bush administration. So, to the extent that you had political forces

that were

explicitly driving the process, those were the motivations. It was

certainly

not some broad altruism toward a part of the population in which the

political

leadership of the country at the time never had any interest whatever.

Is there

such a thing like “do-goodism” in Washington?

There is

“do-wellism.”

What is

this?

Large parts of the

process are driven by a very

strong desire to increase one’s income and wealth. I’m not saying that

everybody in Washington

is a crook. I’m not saying that there aren’t principled public servants

even

now. But to say that they were dominating housing policy in the last

decade is

a very silly view.

But does

at least

Goldman Sachs do “God’s Work” here on earth?[vii]

Well, I think you have

to ask Mr. Blankfein

that question. (laughs) The reality

is: these firms have enormously increased their share of American

economic

activity in the last twenty to thirty years. At the peak they were

making, or

perhaps even still, 40 % or more of total corporate profits. They were

paying

10 % of total wages. This is vastly out of proportion of the need for

financial

services in any economy and in a substantially predatory relationship

with the

rest of economic activity.

So, the task facing us

is to figure out how to

bring this sector under control, how to shrink it and

how to restructure it, so that it is

formed of firms which actually compete with each other rather of

operating

essentially as a large informal cartel with an implicit government

guarantee

for the most wealthy and powerful operations in the business.

Let me give you a

parallel. In many countries,

in modern times, one had a large state-owned airline which provided

rather poor

service and did not exploit the potential of that industry. An extreme

example

of that was in China,

where you had one large, socialist airline. The Chinese did not

privatize that

firm. Rather they broke it up into many smaller airlines and allowed

new

companies to enter the market. Some were owned by the state, some by

provinces

and some by municipalities. It created an environment of enormous

competitiveness between companies, and it enormously improved the

service and

forced a great modernization of the industry. (As an aside, I’ve heard

on good

authority that the Chinese got the idea for this from one of the 20th

centuries greatest physicists, the American John Archibald Wheeler.)

That is the kind of

thing that we need to do

with the banking industry. Banks are private-public partnerships. It

can be

structured in a number of different ways. And the idea that you need to

have a

sector which is dominated, with 60 % of the industry in a handful of

multinational firms -- whose business

models are highly speculative, who are involved in the avoidance of

taxes and

regulation on a multi-national basis -- this is absurd. It’s a very

poor way to

run a modern economy, and to the extent that we don’t deal with this

structural

problem, we are going to continually run into problems of instability

into the

future.

With

regard to the

trickle-up bailouts from autumn of 2008 – that you opposed[viii]

– and onward: those

trillions of dollars spent were not spent by “do-gooders” in

the interest

of protecting bank depositors or the general public; they went to

protect bank

bondholders, is this right?

Yes, that is

essentially correct. But it was

not just bondholders who were protected. Shareholders and holders of

subordinated debt, which is risk capital, were also protected; in a

resolution

they would have been left out. That’s a serious problem. There was no

real

reason to do that. In a normal work-regulatory intervention in a bank

which is

insolvent or at risk of insolvency, the historical effective practice

of the

regulatory agencies was to ensure that shareholders and subordinated

debt-holders, who were after all putting their money at risk in order

to earn a

higher return in good times, were wiped out. They should have been.

That is first

of all necessary to preserve the basic hierarchy of returns and risks

in the

financial markets, and necessary to establish in a credible and

decisive way

the need for changing practices in the financial sector.

Isn’t it

the case that

almost by definition, money given, like via these bailouts, to

corporations or

banks will show up most quickly as improvements in corporate earnings,

and then

slightly later, as executive compensation?

The

phrase “money given” is a

little bit vague. What was done in this case primarily was a purchase

of

preferred equity in the banks and that does not show up as earnings.

The best

way to think of a capital injection, technically, is as a form of

regulatory

forbearance. It was a way of saying to the banks, “we are not going to

impose

upon you the restructuring of your balance sheets that would have been

required

by recognition that your capital had been diminished to the extent that

it had

actually been diminished.” From a regulatory standpoint, buying

preferred

shares is essentially the same thing as reducing a capital requirement.

Two

other things then

happened. The Federal Reserve reduced

the cost of funds to the bank existent to zero, and the Treasury made

it clear

that the large institutions were not going to be permitted to fail.

This was

the message of the stress tests, which were clearly, I’d say, one of

the most

successful public relations exercises of recent times. They didn’t

persuade

people that the banks were sound. They simply persuaded people that the

government would not let them fail. The government was not going to

allow the

banks’ unsoundness to trigger the normal actions that would have

brought them

into conservatorship and ultimately to resolution.

As a

result, the banks were able to

begin borrowing extensively. Some of these funds apparently found their

way, by

what channels is not entirely clear, right back into speculative asset

markets.

This meant that the stock market recovered and that commodity markets

recovered

and people who were investing in those markets at the bottom with

speculative

hopes have been very, very greatly rewarded. I think that’s where the

bank

profits partly come from. That, plus an enormous amount of interest

arbitrage

which is to say, borrowing from the central bank at zero and then

lending back

to the treasury or similar, very secure, non risk-taking entities at 3

or 4 %,

is also a way of making a lot of money if you do it on a sufficiently

large

scale. Those things have given the banks very good earnings and enabled

them to

resume paying bonuses.

And what

do you think about the plan of the Securities and

Exchange Commission

(SEC) to

abolish the legal right to redeem money

market accounts?[ix]

Do

I have a comment on it? I’m not on top of that one.

At the end

of “The Predator State”

you are explaining the consequences of the breakdown of the Bretton

Woods

agreement by Richard Nixon in 1971. May I summarize my reading of

it?

Sure.

Well, in

the chapter “Paying For It” you

explain that according to the system established in 1944, the U.S.

current account deficit – and by extension its public budget deficit –

was

limited by an obligation to exchange foreign-held dollars for gold.

Richard

Nixon abolished that arrangement. You are arguing now that since the

early

1980s, the world has held the T-bonds that the U.S. chose to issue. You

acknowledge that the system is neither robust nor just, but you insist

that so

long as it lasts, it doesn't discipline the U.S.

budget and therefore doesn't constrain U.S. government spending in any

way. Is this right so far?

Correct,

sure.

I mention

this because this is basically, at least as far as I understand it, the

financial

backbone of the stimulus package you want to see taken place? And if

this is

the case how would then a stimulus package look like if you could have

it your

way?

First of

all, it’s very clear that

the United States government is not constrained externally, and it’s

clear that

quite apart from the stimulus package, the automatic stabilizers and

the

financial rescue, which greatly ballooned the public debt of the United

States,

have had no effect on the ability of the United States government to

fund

itself and no effect on the interest rates that the government pays.

So, it, I

think, follows from that logically and straight-forwardly that we have

nothing

to fear from additional efforts as long as they are necessary. And

they’re

obviously very clearly necessary. So the question is: what should be

the

structure of those efforts?

I’ve

always taken exception to the

constant reference to “stimulus” as the policy objective, because

implied in

that word is the idea that all one needs to do is to undertake one or

more

relatively short term spending sprees, on whatever happens to be

available at

the moment, and that this will somehow return the economy to its

pre-crisis

state, putting it on a path of what economists like to call

“self-sustaining

growth.” I maintain that in the present environment there is no such

thing as a

return to self-sustaining growth. There will be no return to the

supposedly

normal conditions, which were in fact, from a historical point of view,

highly

abnormal, of the 1990s and 2000s.

What one

needs is to set a

strategic direction for renewal of economic activity. We need to create

the

institutions that will support that direction.

Those institutions are public institutions, which create a

framework for

private activity. This is the way it is done. It is the way countries

have

always developed in the past and, to the extent that they are

successful, they

will always do so in the future or they won’t succeed. Seventy years

ago when

we were in the Great Depression, they built a national infrastructure:

roads,

airfields, schools, power-grids – this kind of thing was the priority.

In the

post-war period, the creation and maintenance of a large middle class

with

social security, with medical care, with housing programs, universities

– these

were the priorities of the post-war period.

Now we

clearly face an enormous

challenge with energy and climate. It’s a challenge that requires us to

think

in very creative ways, in very ambitious ways about how to change how

we live,

so as to make life on the planet tolerable a century or two centuries

hence.

This is a huge challenge. It requires design, planning, implementation,

something with enormous potential for providing employment because

things have

to be done, enormous potential for guiding new public and private

investment

because one has to provide people with the means of making it realistic

for

individual activity to support this larger objective. And that is the

way to

move toward a renewed economic

expansion. This strikes me very far from being a stimulus

proposal. It

is a proposal for setting a new strategic direction for the economy and

doing

so over a relatively long time horizon with a view that you’re

sustaining

effort for 15, 20, 30 years. That’s the way I think you need to think

about

this.

Just to

wrap up a long answer to a

short question: Why can’t we go back to the pre-crisis period? The

answer is

that restructuring of the private household debts is an enormous task

which

necessarily takes a very long period of time. During that time, the

pre-crisis

pattern of increasing debt will not resume. The asset against which the

American household sector collateralized its debt for 15 to 20 years,

its

housing, has radically fallen in financial value. The houses are still

there

but you can’t sell them for nearly as much as you could have three

years ago.

And that is a structural impediment to returning to the previous

pattern of

economic expansion. And that impediment isn’t going to be removed in

any short

period of time for the simple reason that the houses remain there as an

excess

supply on the market and they remain therefore as a drag on housing

prices.

Do you see

a bit of a problem in the fact that the Federal Reserve bought

approximately 80

percent of the U.S.

Treasury securities issued in 2009?[x]

No.

Why not?

Well,

say what problem are you

hinting at here, then I’ll explain.

Some

people might say that this does fulfil the requirements for a Ponzi

Scheme.

It

certainly isn’t remotely related

to a Ponzi Scheme. To be very clear, a Ponzi Scheme is a scheme in

which a

private party is issuing debts which can only be serviced by issuing

more debts

to cover the interest. This is not a constraint on a sovereign

government which

controls its own currency. Never is, never will be. There is a lot of

loose

rhetoric about things like Ponzi Schemes and national bankruptcy which

is

typically the work of people who neither know nor care much about what

they’re

talking about.

You

already said that energy should be part of a stimulus package or a

larger plan.

What do you think like for example about the immediate implementation

in the

U.S. of a national Feed-in Tariff mandating that electric utilities pay

3 % above

market rates for all surplus electricity generated from renewable

sources, as

Mike Ruppert suggests in his new book “Confronting

Collapse”?[xi]

In Germany, the Feed-in Tariff was

quite a success story that created a huge amount of new jobs. Would you

support

this implementation?

I would need to study

it, so I’m not

sufficiently familiar to say. But it does sound, as you just described,

like a

promising line of attack.

With

regard to the

energy problem, I would like to know if you take the phenomenon of Peak

Oil

seriously, and if so: why do you think that the

financial, economic and

political establishment around the globe wants to keep quiet about it

or

dismiss it as “nonsense”[xii]

even though there

seems to be a good amount of evidence that the world soon won't be able

to meet

energy demands anymore?

I have read a fair

amount on Peak Oil and I do

think that the argument in its favor is qualitatively different from,

and more

serious than, earlier alarmist warnings about the supply of oil. The

peak oil

proposition relates to supplies of conventional oil, and it relates to

the idea

that there is a normal (bell) curve associated with discovery and

production

over time. That strikes me as a plausible hypothesis, and as one that

back in 1956,

successfully predicted he peak in conventional oil production in the

United States

in 1970. So it’s been around for a long time. So, I do think that it’s

a

proposition which needs to be taken seriously. As to your

characterization of

the actions and motives of large and powerful interests, I don’t have a

theory

on that.

As Chair

of the Board of Economists for Peace and Security: isn’t

the whole ongoing “War on Terror” a fraud that is really driven by

the geopolitical competition for oil?

That’s a compound

question. First part, is the

“War on Terror” a fraud? I have always found that the concept of war on

a

method to be a very dangerous way of arguing because it basically

covers

anything the speaker wants to cover. It is something which can have no

end, no

limit, no success. It’s a construct which justifies the permanent

commitment of

resources to an exercise in futility at best, and at worst a cover for

all

kinds of other purposes. And your suggestion is that one of those

purposes is

the struggle for the control of oil.

My answer to that is:

the interest of major oil

producers can be served without, and has been historically served

without

physical access to production fields. The oil majors’ interests haven’t

depended on owning oil fields for many decades. So, when you ask what

were the

interests of energy producers in the Iraq War -- and without saying

that they

played the dominant role, which I think is very, very uncertain, in the

decision to undertake that war -- there’s no evidence whatever that

their

interest was to go over and produce the Iraqi fields. Quite the

contrary, since

the war they’ve not made a very serious effort to do that.

There’s been very

little new international

investment in Iraq

in the post-war period. Very little certainly in the traditional

oil-producing

regions of Iraq.

So, I think that their interests are served perhaps by preventing

excess supply

that might otherwise have come on-line from Iraq from doing so, because

that

would have undermined the markets for oil produced in places where

costs are

much higher. One could make an argument along those lines. It strikes

me as

being economically more coherent, but I’m not going to get into the

position of

trying to interpret the entire exercise in Iraq along those lines

because I

think, in point of fact, that other factors, including power politics

in the

Middle East, and including domestic politics in the United States, also

played

extremely important roles.

And there are people,

who have studied George

W. Bush, who write that he believed that you can’t be a successful

president of

the United States

without a war. Perhaps the whole matter was as simple as that. I don’t

know if

that’s true or not, but one has to be, as a historical matter, very

open-minded

about the reasons why a particular government of the United States

takes a particular

action of this kind.

The

biggest

“treasure”, I believe, that the Bush Administration left, are the

records of

the National Energy Policy Development Group, NEPDG, run by

Vice-President

Richard Cheney in Spring of 2001. Those records are kept secret even

though the

American public did pay for it – and not Mr. Cheney himself. Given the

fact,

that we can strongly assume that those records must be very precise

when it

comes to oil reserve numbers, and given the fact, that we have for

years now

all this debate about reserve estimates, wouldn’t it be time to open

this “safe

deposit box” in order to let the world see how much oil there is really

left?

Again, a question with

a number of predicates

that I can’t speak to with authority. I don’t know what is in those

files.

Well,

they’re secret.

Yes. I do agree that

files of this type should

be made public. If there is an argument, which undoubtedly some people

will

make, for a national security reason not to make them public, then an

appropriate procedure, which we have followed in this country in the

past, is

to appoint a panel of independent outsiders, not previously connected

to the

government, to review the documents and to make them public unless

there is a

compelling reason not to, with arguments about what is compelling and

not-compelling ultimately resolved by the president himself. That’s a

model

that has been applied successfully in the past in the United States on

a matter of this

kind. I think it would be very useful to do it in this and other

instances on

the conduct of the Bush administration.

Two

questions on Ron

Paul’s bill to audit the Fed, or more precisely the House Resolution

1207

Federal Reserve Transparency Act of 2009, a bill requiring that an

audit of

both the Fed's Board of Governors and the Federal Reserve Banks be

completed

and reported to Congress before the end of 2010. You support this bill.

Yes.

Why?

The transparency of

the Federal Reserve is an

old battle between the Federal Reserve and Congress which I have been a

party

to since my days on the staff of what was then the Banking Committee of

the

House of Representatives in the mid-1970s. The bill to audit the Fed at

that

time was a project of the great Texas Congressman Wright Patman who, up

until

1975, had been Chair of the Banking Committee and had served in

Congress from

1929 until his death in the late 1970’s. I also worked on the

development of a

regular reporting procedure for the Federal Reserve, the Humphrey-Hawkins hearings on

monetary

policy, which has been in place ever since. After my days on that

Committee,

Chairman Henry B. Gonzales worked to expand the transparency of the

Federal

Reserve, particularly with respect to making its archives open after a

certain period

of time.

In every case,

systematically, the pattern is

the same. The Federal Reserve always resists having its operations

investigated. But when it cannot resist any longer, it adjusts. And

people

quickly realize that the agency actually functions better under

transparency

than under the previous regime of secrecy. This is perfectly normal.

Secrecy,

in almost all aspects of federal government, is a cover for inadequacy

and

inability to explain yourself in public. The Congress itself went

through major

reforms of this kind in the 1970’s and everybody agrees, I think, that

they led

to very significant improvements in the way Congress did business at

least for

a time. That’s point number one.

Point number two is

that in the crisis that we

are just going through, the Federal Reserve went to extraordinary steps

to

support the financial sector. Extraordinary steps, steps which

it has persistently refused to present

a full accounting of to the Congress. The Chairman of the Federal

Reserve has

arrogated to himself a power that he does not have in law, to withhold

information from the Congress. The Federal Reserve is not the European

central

bank. It’s not a constitutionally separate part of the governing

structure. The

Federal Reserve is an agency of the United States government, created

by an act of Congress. The Congress has unquestionable oversight

authority of

the Federal Reserve and a presumptive right to any information it

wants. The

Congress is a constitutional branch of government, the Federal Reserve

is not.

So this is a fundamental issue in the American system.

My view is that

information requested by

Congress or by the Government Accountability Office, which is the

auditing arm

of the Congress, should be provided. The issue of whether that

information

should be kept confidential or not is a matter for Congress to decide,

not for

the Federal Reserve. There is ample practice in other parts of the

government

where this works very well. There has never, so far as I know, been a

significant leak of national security information from Congress.

Congress is

briefed, and leadership of the intelligence committees is briefed on

sensitive

covert operations carried out by the national intelligence agencies.

Security

on that has been remarkably good. Nothing that the Federal Reserve does

has

remotely that degree of national security sensitivity.

The justification for

secrecy is only about

money and to some degree about – so they argue --the reputation of

particular

firms, whether they are going to the discount window and whether this

signals

that they may be in some kind of difficulty. These are concerns of some

importance in normal times. They are concerns that are totally

overridden in a

moment of crisis, when every financial firm was in severe difficulties,

and

everybody knows this fact.

The

issue before us, is to ensure that actions of the Federal Reserve were

conducted in a way consistent with the public interest and with the

detachment

that one would normally expect of a public official from purely private

financial

considerations, especially favouritism to one firm as opposed to

another. Those

are issues which are legitimate to investigate, in fact it’s imperative

to do

so. Absent a full investigation, most people are going, rightly, to be

very

suspicious.

The point of an audit

is to get to the bottom

of that matter. It’s a bipartisan bill. Ron Paul picked up the idea

from his

fellow Texan on the other side of the spectrum, Wright Patman, and he’s

been

joined by progressive member from Florida, Alan Grayson, who is a very

competent fellow, knows what he’s doing. It’s something which needs to

be

treated with great seriousness. It’s also something that has a lot of

popular

support, but it is not a demagogical “populist” measure. It’s a measure

that

gets to the heart of the correct relationship between the Congress and

the

central bank in the constitutional structure of the government of the

United States.

Is it

any surprise to

you that most of those economists who oppose the audit the Fed bill are

actually on the payroll of the Fed?[xiii]

This is a fact which

has been well documented

by a close colleague of mine here at the LBJ School,

Robert Auerbach. The Federal Reserve engages in a very wide-spread

practice of

consulting contracts to economists who repay the Federal Reserve with

loyalty.

Since this is now well-known, it’s not surprising that no one takes the

position of an economist on a matter like this very seriously.

Do you

agree with Ron

Paul that the “Fed will self destruct when it destroys the dollar”?[xiv]

Is the Fed indeed

destroying the dollar? And do you see signs that a run on the dollar

might

start soon?[xv]

No, no, and no. I’ve

spoken favourably of Ron

Paul about this question of the audit. He is in other respects a very

strange

person to have captured the mantle of populism because, while the

populists were

in favour of an elastic currency and their great cause was free silver

(the use

of silver as a monetary metal), Ron Paul is a hard money man. To the

extent

that he has a clear vision of a monetary system, it’s a vision that

would have

been comfortable in the board room of a New York bank in the late 19th

century -- that the dollar has to be good as gold, etc., etc. He has

held this

view for many years. As a very young man, I remember debating him on

radio in Washington D. C. about this and this

was in the mid 1970’s.

The dollar is the

national currency of a very

large economy, and it is also the transactions and reserves currency of

a very

large share of world trade. The reasons for this are that the US is a

very big place, and the US

government does not have any problem, never will have any problem

servicing its

own debts in dollars. So, the US

has a great advantage in the world of being the target of flights to

quality,

and we provide a service to the world economy, which does not cost us

very much

to provide. It’s fundamentally a matter of existing institutions and

reputation

and scale of American economic activity. This is not going to go away

in my

view, and it’s not threatened by reserve holdings of Japan

or China

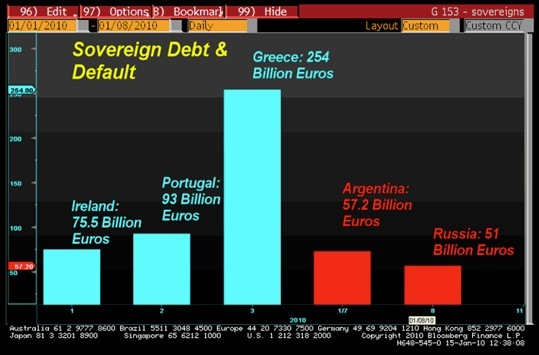

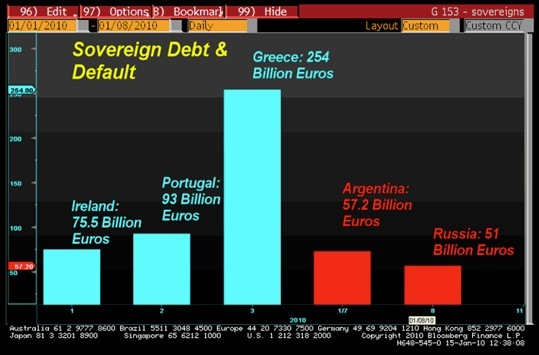

either. It is much more likely that Greece,

Portugal, or Spain will be forced from the euro than it is

that Texas or even California would be forced from the dollar.

Much more likely.

For this reason,

everything in world currency

terms has to be assessed in relative terms. The institutions that

support the

dollar, the public institutions, the Federal Reserve and the US

Treasury, are

much more flexible and better-adapted to economic management,

generally, and

the crisis in particular, than is the euro system. The Europan system

is a

system managed by a rigidly constrained central bank and by a loose

network of

finance ministers who are ridden by ideological differences and unable

to turn to

bring the power of the European economy to the assistance of the

economies on

the periphery of the euro zone that had been most severely effected in

fiscal

terms by the crisis.

The world investment

communities are well aware

that what happened in November 2008 was

that the dollar rescued the euro, not the other way around. This was

done by a

massive extension of swap of currencies from the Federal Reserve to the

euro zone

to alleviate a massive shortage of dollars caused by banks and others

hoarding

dollar assets and dumping dollar liabilities. It’s true that the euro

has gone

up and the dollar has gone down since then, but the basic asymmetry in

these

institutional arrangements and capacities remains.

So, I think Mr. Paul

is really, first of all,

wrong, alarmist and to some extent politically motivated. In spite of

everything that’s gone wrong in the American economy it’s quite

unwarranted to start

talking as though there’s an imminent collapse of the dollar. All

reserve

systems are fragile. All monetary regimes can collapse. It’s not

excluded that

something very bad could happen. The costs of something like this are

however

very large, and the most likely thing is that the existing system, the

existing

role of the dollar, will continue and as I say for the reasons that

I’ve just

given, the euro is in no position to replace the dollar.

Thank

you very much for taking your time,

Professor Galbraith!

SOURCES:

[iii] John Kenneth

Galbraith: “The Great Crash 1929”, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston,

1954.

[iv] Lars Schall:

“Marshall Auerback: ‘Many years of economic stagnation’”, published at MMNews

on September 7, 2009 under: http://www.mmnews.de

[v] Michael Mross: “Henkel: Politik

wrackt ab”, published at MMNews on

November 27, 2009 under: http://www.mmnews.de

In this op-ed,

Professor Galbraith said the bailout plan of September

2008 wasn’t necessary, and any rescue could have been handled by

expanding

existing programs: “Now that all five big

investment banks — Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, Lehman Brothers,

Goldman Sachs

and Morgan Stanley — have disappeared or morphed into regular banks, a

question

arises.

The point of the

bailout is to buy assets that are illiquid but not worthless. But

regular banks

hold assets like that all the time. They’re called “loans.”

With banks, runs

occur only when depositors panic, because they fear the loan book is

bad.

Deposit insurance takes care of that. So why not eliminate the

pointless

$100,000 cap on federal deposit insurance and go take inventory? If a

bank is

solvent, money market funds would flow in, eliminating the need to

insure those

separately. If it isn’t, the FDIC has the bridge bank facility to take

care of

that.

Next, put half a

trillion dollars into the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. fund — a

cosmetic

gesture — and as much money into that agency and the FBI as is needed

for

examiners, auditors and investigators. Keep $200 billion or more in

reserve, so

the Treasury can recapitalize banks by buying preferred shares if

necessary —

as Warren Buffett did this week with Goldman Sachs. Review the

situation in three

months, when Congress comes back. Hedge funds should be left on their

own. You

can’t save everyone, and those investors aren’t poor.

With this solution,

the systemic financial threat should go away. Does that mean the

economy would

quickly recover? No. Sadly, it does not. Two vast economic problems

will

confront the next president immediately. First, the underlying housing

crisis….The second great crisis is in state and local government.”

[ix] Geoffrey Batt: “This Is The Government: Your

Legal Right To Redeem Your Money Market Account Has Been Denied”,

published at Zero Hedge on January 3, 2010 under: http://www.zerohedge.com

Batt writes: (N)ew

regulations proposed by the

administration, and specifically by the ever-incompetent Securities and

Exchange Commission, seek to pull one of these three core pillars from

the

foundation of the entire money market industry, by changing

the

primary assumptions of the key Money Market Rule 2a-7. A key

proposal in

the overhaul of money market regulation suggests that money market fund

managers will have the option to "suspend redemptions to allow

for

the orderly liquidation of fund assets." You read that right:

this does not refer to the charter of procyclical, leveraged,

risk-ridden,

transsexual (allegedly) portfolio manager-infested hedge funds like

SAC,

Citadel, Glenview or even Bridgewater (which in light of ADIA's latest

batch of

problems, may well be wishing this was in fact the case), but the heart

of

heretofore assumed safest and most liquid of investment options: Money

Market

funds, which account for nearly 40% of all investment company assets.

The next

time there is a market crash, and you try to withdraw what you thought

was

"absolutely" safe money, a back office person will get back to you

saying, "Sorry - your money is now frozen. Bank runs have

become

illegal." This is precisely the regulation now proposed by the

administration. In essence, the entire US capital market is now a hedge

fund, where even presumably the safest investment tranche can be locked

out

from within your control when the ubiquitous "extraordinary

circumstances" arise. The second the game of constant offer-lifting

ends,

and money markets are exposed for the ponzi investment proxies they

are,

courtesy of their massive holdings of Treasury Bills, Reverse Repos,

Commercial

Paper, Agency Paper, CD, finance company MTNs and, of course, other

money

markets, and you decide to take your money out, well - sorry, you are

out of

luck. It's the law.

A brief primer on money markets

A

very succinct explanation of what money

markets are was provided by none other than SEC's Luis Aguilar on June

24,

2009, when he was presenting the case for making

even the

possibility of money market runs a thing of the past. To wit:

Money

market funds were founded nearly 40 years ago. And, as is well known,

one of the hallmarks of money market funds is their ability to maintain

a

stable net asset value — typically at a dollar per share.

In the time they have been around, money market

funds have grown enormously

— from $180 billion in 1983 (when Rule 2a-7 was first adopted), to $1.4

trillion at the end of 1998, to approximately $3.8 trillion at the end

of 2008,

just ten years later. The Release in front of us sets forth

a number of informative statistics but a few that are of particular

interest

are the following: today, money market funds account for

approximately

39% of all investment company assets; about 80% of all U.S. companies

use money

market funds in managing their cash balances; and about 20% of the cash

balances of all U.S. households are held in money market funds.

Clearly, money market funds have become part of the fabric by which

families,

and companies manage their financial affairs.

When

the Reserve fund broke the buck, and it

seemed like an all-out rout of money markets was inevitable, the result

would

have been a virtual elimination of capital access by everyone: from

households

to companies. This reverberated for months, as the also presumably

extremely

safe Commercial Paper market was the next to freeze up, side by side

with all

traditional forms of credit. Only after the Fed stepped in an

guaranteed money

markets, and turned on the liquidity stabilization first, then

quantitative

easing spigot second, did things go back to some sort of new normal.

However,

it is only a matter of time before the patchwork of band aids holding

the dam

together is once again exposed, and a new, stronger and, well,

"improved" run on the electronic bank materializes. It is precisely

this contingency that the SEC and the administration are preparing for

by

"empowering

money

market fund boards of directors to suspend redemptions in extraordinary

circumstances to protect the interests of fund shareholders."

A

little more on money

markets:

Money

market funds seek to limit exposure to losses due to credit, market,

and liquidity risks. Money market funds, in the United States, are

regulated by the

Securities and Exchange Commission's (SEC) Investment Company Act of

1940. Rule

2a-7 of the act restricts investments in money market funds by quality,

maturity and diversity. Under this act, a money fund mainly

buys the

highest rated debt, which matures in under 13 months. The portfolio

must

maintain a weighted average maturity (WAM) of 90 days or less and not

invest

more than 5% in any one issuer, except for government securities and

repurchase

agreements.

Ironically, the proposed

change to Rule 2a-7 seeks to

make dramatic changes to the composition of MMs: from 90 days, the WAM

would

get shortened to 60 days. And this is occurring at a time when the

government

is desperately seeking to find ways of extending maturities and

durations of

short-term debt instruments: by reverse rolling the $3.2 trillion

industry, the

impetus will be precisely

the reverse of what should be happening, as more

ultra-short maturity instruments are horded up, leaving a dead zone in

the

60-90 day maturity window. Some other proposed changes to 2a-7 include

"prohibiting the funds from investing in Second Tier securities, as

defined in Rule 2a-7. Eligible securities would be redefined as

securities

receiving only the highest, rather than the highest two, short-term

debt

ratings from a requisite nationally recognized securities rating

organization. Further, money market funds would be permitted to acquire

long-term unrated securities only if they have received long-term

ratings in

the highest two, rather than the highest three, ratings categories." In

other words, let's make them so safe, that when

the time comes, nobody will have access

to them. Brilliant.

[x] compare “Ponzi

Scheme:

The Federal Reserve Bought Approximately 80 Percent Of U.S. Treasury

Securities

Issued In 2009”, published at The

Economic Collapse under:

http://theeconomiccollapseblog.com

[xi] compare

Michael C. Ruppert: “Confronting Collapse. The Crisis

of Energy and Money in a Post

Peak Oil World. A

25-Point Program for Action”, Chelsea

Green

Publishing, December 2009.

[xii] compare Michael C. Lynch:

“Nonsense, Peak Oil, and

Oil Prices”, published at Business Week

on December 17, 2009 under: http://bx.businessweek.com

and Jeff Poor: “CNBC’s Kilduff: $100 Oil in Next Six Months.

Network

contributor says China pushing prices higher; blasts

the peak oil theory as dated”, published at Business

& Media Institute on January 12, 2010 under:

http://www.businessandmedia.org/

Jeff Poor writes: Kudlow asked

if we needed to rely on

“windmills on Nantucket” as a new power source

and Kilduff told Kudlow that wasn’t a good idea. But he also refuted

the theory

of peak oil.

“Well

if we do it will be very expensive, Larry,” Kilduff said. “And I have

been

opponent of the peak oil theory my entire career, not for the least of

which

reasons was that this morning's announcement from McMoRan Exploration

and

several other companies who might have made the oil find of a decade in

shallow

Gulf waters. And it's a real game-changer for the companies involved

and it’s

in a neighborhood that is going to be one of the biggest finds in

decades.”

Peak

oil is a theory that there exists a point in time when the maximum rate

of

global petroleum extraction is reached. However, a

recent BusinessWeek article disputed

this theory and Kilduff explained that when

this idea was conceived, there wasn’t the technology to confirm such a

theory.

“With

new technologies every day, Larry,” Kilduff said. “This was thigh

problem with

the peak oil theory from the beginning. How could you have the hubris

to tell

me that we had the knowledge and the science to help us find this oil?

Our cell

phones were as big as cars. Now they fit in your pocket, right? Now,

the same

thing goes for satellite technology that can find oil and new drills

that can

get to places without harming the lands anywhere near what we had in

the '50s

and '60s and '70s.”

We Are So Screwed

"Our

immersion in the details of crises that have arisen over the past eight

centuries and in data on them has led us to conclude that the most

commonly repeated and most expensive investment

advice ever given in the boom just before a financial

crisis stems from the perception that 'this time is different.' "Our

immersion in the details of crises that have arisen over the past eight

centuries and in data on them has led us to conclude that the most

commonly repeated and most expensive investment

advice ever given in the boom just before a financial

crisis stems from the perception that 'this time is different.'

"That advice, that the old rules of valuation no longer

apply,

is usually followed up with vigor. Financial professionals and, all too

often, government leaders explain that we are doing things better than

before, we are smarter, and we have learned from past mistakes. Each

time, society convinces itself that the current boom, unlike the many

booms that preceded catastrophic collapses in the past, is built on

sound fundamentals, structural reforms, technological innovation, and

good policy."

- This Time is Different (Carmen M. Reinhart and

Kenneth Rogoff)

When does a potential crisis become an actual crisis, and how

and

why does it happen? Why did most everyone believe there were no

problems in the US (or Japanese or European or British) economies in

2006? Yet now we are mired in a very difficult situation. "The subprime

problem will be contained," said now controversially confirmed Fed

Chairman Bernanke, just months before the implosion and significant Fed

intervention. I have just returned from Europe, and the discussion

often turned to the potential of a crisis in the Eurozone if Greece

defaults. Plus, we take a look at the very positive US GDP numbers

released this morning. Are we finally back to the Old Normal? There's

just so much to talk about...

The Statistical Recovery Has Arrived

Before we get into the main discussion point, let me briefly

comment

on today's GDP numbers, which came in at an amazingly strong 5.7%

growth rate. While that is stronger than I thought it would be (I said

4-5%), there are reasons to be cautious before we sound the "all clear"

bell.

First, over 60% (3.7%) of the growth came from inventory

rebuilding,

as opposed to just 0.7% in the third quarter. If you examine the

numbers, you find that inventories had dropped below sales, so a

buildup was needed. Increasing inventories add to GDP, while,

counterintuitively, sales from inventory decrease GDP. Businesses are

just adjusting to the New Normal level of sales. I expect further

inventory build-up in the next two quarters, although not at this

level, and then we level off the latter half of the year.

While rebuilding inventories is a very good thing, that growth

will

only continue if sales grow. Otherwise inventories will find the level

of the New Normal and stop growing. And if you look at consumer

spending in the data, you find that it actually declined in the 4th

quarter, both annually and from the previous quarter. "Domestic demand"

declined from 2.3% in the third quarter to only 1.7% in the fourth

quarter. Part of that is clearly the absence of "Cash for Clunkers,"

but even so that is not a sign of economic strength.

Second, as my friend David Rosenberg pointed out, imports fell

over

the 4th quarter. Usually in a heavy inventory-rebuilding cycle, imports

rise because a portion of the materials businesses need to build their

own products comes from foreign sources. Thus the drop in imports is

most unusual. Falling imports, which is a sign of economic retrenching,

also increases the statistical GDP number.

Third, I have seen no analysis (yet) on the impact of the

stimulus

spending, but it was 90% of the growth in the third quarter, or a

little less than 2%.

Fourth (and quoting David): "... if you believe the GDP data -

remember, there are more revisions to come - then you de facto must

be

of the view that productivity growth is soaring at over a 6% annual

rate. No doubt productivity is rising - just look at the never-ending

slate of layoff announcements. But we came off a cycle with no

technological advance and no capital deepening, so it is hard to

believe that productivity at this time is growing at a pace that is

four times the historical norm. Sorry, but we're not buyers of that

view. In the fourth quarter, aggregate private hours worked contracted

at a 0.5% annual rate and what we can tell you is that such a decline

in labor input has never before, scanning over 50 years of data,

coincided with a GDP headline this good.

"Normally, GDP growth is 1.7% when hours worked is this weak,

and

that is exactly the trend that was depicted this week in the release of

the Chicago Fed's National Activity Index, which was widely ignored. On

the flip side, when we have in the past seen GDP growth come in at or

near a 5.7% annual rate, what is typical is that hours worked grows at

a 3.7% rate. No matter how you slice it, the GDP number today

represented not just a rare but an unprecedented event, and as such, we

are willing to treat the report with an entire saltshaker - a few

grains won't do."

Finally, remember that third-quarter GDP was revised downward

by

over 30%, from 3.5% to just 2.2% only 60 days later. (There is the

first release, to be followed by revisions over the next two months.)

The first release is based on a lot of estimates, otherwise known as

guesswork. The fourth-quarter number is likely to be revised down as

well.

Unemployment rose by several hundred thousand jobs in the

fourth

quarter, and if you look at some surveys, it approached 500,000. That

is hardly consistent with a 5.7% growth rate. Further, sales taxes and

income-tax receipts are still falling. As I said last year that it

would be, this is a Statistical Recovery. When unemployment is rising,

it is hard to talk of real recovery. Without the stimulus in the latter

half of the year, growth would be much slower.

So should we, as Paul Krugman suggests, spend another trillion

in

stimulus if it helps growth? No, because, as I have written for a very

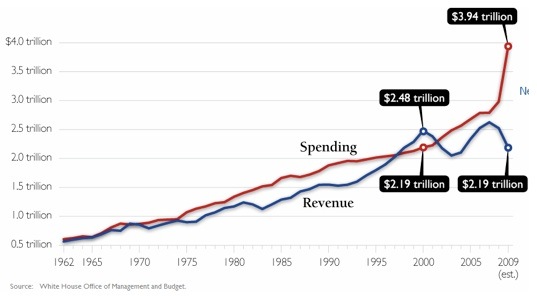

long time, and will focus on in future weeks, increased deficits and

rising debt-to-GDP is a long-term losing proposition. It simply puts

off what will be a reckoning that will be even worse, with yet higher

debt levels. You cannot borrow your way out of a debt crisis.

This Time Is Different

While I was in Europe, and flying back, I had the great

pleasure of reading This Time is Different, by Carmen M.

Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, on my new Kindle, courtesy of Fred Fern.

I am going to be writing about and quoting from this book for

several weeks. It is a very important work, as it gives us the first

really comprehensive analysis of financial crises. I highlighted more

pages than in any book in recent memory (easy to do on the Kindle, and

even easier to find the highlights). Rather than offering up theories

on how to deal with the current financial crisis, the authors show us

what happened in over 250 historical crises in 66 countries. And they

offer some very clear ideas on how this current crisis might play out.

Sadly, the lesson is not a happy one. There are no good endings once

you start down a deleveraging path. As I have been writing for several

years, we now are faced with choosing from among several bad choices,

some being worse than others. This Time is Different offers

up some ideas as to which are the worst choices.

If you are a serious student of economics, you should read

this

book. If you want to get a sense of the problems we face, the authors

conveniently summarize the situation in chapters 13-16, purposefully

allowing people to get the main points without drilling into the

mountain of details they provide. Get the book at a 45% discount at Amazon.com.

Buy it with the excellent book I am now reading, Wall

Street Revalued, and get free shipping.

A Crisis of Confidence

Let's lead off with a few quotes from This Time is

Different, and then I'll add some comments. Today I'll focus on

the theme of confidence, which runs throughout the entire book.

"But highly leveraged economies, particularly those in which

continual rollover of short-term debt is sustained only by confidence

in relatively illiquid underlying assets, seldom survive forever,

particularly if leverage continues to grow unchecked."

"If there is one common theme to the vast range of crises we

consider in this book, it is that excessive debt accumulation, whether

it be by the government, banks, corporations, or consumers, often poses

greater systemic risks than it seems during a boom. Infusions of cash

can make a government look like it is providing greater growth to its

economy than it really is. Private sector borrowing binges can inflate

housing and stock

prices

far beyond their long-run sustainable levels, and make banks seem more

stable and profitable than they really are. Such large-scale debt

buildups pose risks because they make an economy vulnerable to crises

of confidence, particularly when debt is short term

and needs to be constantly refinanced. Debt-fueled booms all too often

provide false affirmation of a government's policies, a financial

institution's ability to make outsized profits, or a country's standard

of living. Most of these booms end badly. Of course, debt instruments

are crucial to all economies, ancient and modern, but balancing the

risk and opportunities of debt is always a challenge, a challenge

policy makers, investors, and ordinary citizens must never forget."

And this is key. Read it twice (at least!):

"Perhaps more than anything else, failure to recognize the

precariousness and fickleness of confidence-especially

in

cases in which large short-term debts need to be rolled over

continuously-is the key factor that gives rise to the

this-time-is-different syndrome. Highly indebted governments,

banks, or corporations can seem to be merrily rolling along for an

extended period, when bang!-confidence

collapses, lenders disappear, and a crisis hits.

"Economic theory tells us that it is precisely the fickle

nature of confidence,

including its dependence on the public's expectation of future events,

that makes it so difficult to predict the timing of debt crises. High

debt levels lead, in many mathematical economics models, to "multiple

equilibria" in which the debt level might be sustained - or might not

be. Economists do not have a terribly good idea of what kinds of events

shift confidence and of how to concretely assess confidence

vulnerability. What one does see, again and again, in the history of

financial crises is that when an accident is waiting to happen, it

eventually does. When countries become too deeply indebted, they are

headed for trouble. When debt-fueled asset price explosions seem too

good to be true, they probably are. But the exact timing can be very

difficult to guess, and a crisis that seems imminent can sometimes take

years to ignite."

How confident was the world in October of 2006? I was writing

that

there would be a recession, a subprime crisis, and a credit crisis in

our future. I was on Larry Kudlow's show with Nouriel Roubini, and

Larry and John Rutledge were giving us a hard time about our so-called

"doom and gloom." If there is going to be a recession you should get

out of the stock market, was my call. I was a tad early, as the market

proceeded to go up another 20% over the next 8 months.

As Reinhart and Rogoff wrote: "Highly indebted governments,

banks,

or corporations can seem to be merrily rolling along for an extended

period, when bang! - confidence collapses, lenders

disappear, and a crisis hits."

Bang is the right word. It is the nature of human

beings to

assume that the current trend will work out, that things can't really

be that bad. Look at the bond markets only a year and then just a few

months before World War I. There was no sign of an impending war.

Everyone "knew" that cooler heads would prevail.

We can look back now and see where we made mistakes in the

current

crisis. We actually believed that this time was different, that we had

better financial instruments, smarter regulators, and were so, well,

modern. Times were different. We knew how to deal with leverage.

Borrowing against your home was a good thing. Housing values would

always go up. Etc.

Now, there are bullish voices telling us that things are

headed back

to normal. Mainstream forecasts for GDP growth this year are quite

robust, north of 4% for the year, based on evidence from past

recoveries. However, the underlying fundamentals of a banking crisis

are far different from those of a typical business-cycle recession, as

Reinhart and Rogoff's work so clearly reveals. It typically takes years

to work off excess leverage in a banking crisis, with unemployment

often rising for 4 years running. We will look at the evidence in

coming weeks.

The point is that complacency almost always ends suddenly. You

just don't slide gradually into a crisis, over years. It happens!

All of a sudden there is a trigger event, and it is August of 2008. And

the evidence in the book is that things go along fine until there is

that crisis of confidence. There is no way to know when it will happen.

There is no magic debt level, no magic drop in currencies, no

percentage level of fiscal deficits, no single point where we can say

"This is it." It is different in different crises.

One point I found fascinating, and we'll explore it in later

weeks.

First, when it comes to the various types of crises with the authors

identify, there is very little difference between developed and

emerging-market countries, especially as to the fallout. It seems that

the developed world has no corner on special wisdom that would allow

crises to be avoided, or allow them to be recovered from more quickly.

In fact, because of their overconfidence - because they actually feel

they have superior systems - developed countries can dig deeper holes

for themselves than emerging markets.

Oh, and the Fed should have seen this crisis coming. The