Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2008)

Science fiction film is a film genre that uses science fiction: speculative, science-based depictions of phenomena that aren't necessarily accepted by mainstream science. such as extra-terrestrial life forms, alien worlds, esp, and time travel, often along with futuristic elements such as spacecraft, robots, or other technologies. Science fiction films have often been used to focus on political or social issues, and to explore philosophical issues like the human condition. In many cases, tropes derived from written science fiction may be used by filmmakers ignorant of or at best indifferent to the standards of scientific plausibility and plot logic to which written science fiction is traditionally held.

The genre has existed since the early years of silent cinema, when Georges Melies' A Trip to the Moon (1902) amazed audiences with its trick photography effects. The next major example in the genre was the 1927 film Metropolis. From the 1930s to the 1950s, the genre consisted mainly of low-budget B-movies. After Stanley Kubrick's 1968 landmark 2001: A Space Odyssey, the science fiction film genre was taken more seriously. In the late 1970s, big-budget science fiction films filled with special effects became popular with audiences and paved the way for the blockbuster hits of subsequent decades.

| Science Fiction |

|---|

| Books · Authors Films · Television Conventions |

Contents[hide] |

|

|

This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2008) |

Defining precisely which films belong to the science fiction genre is often difficult, as there is no universally accepted definition of the genre, or in fact its underlying genre in literature. According to one definition:

Science fiction film is a film genre which emphasizes actual, extrapolative, or speculative science and the empirical method, interacting in a social context with the lesser emphasized, but still present, transcendentalism of magic and religion, in an attempt to reconcile man with the unknown (Sobchack 63).

This definition assumes that a continuum exists between (real-world) empiricism and (supernatural) transcendentalism, with science fiction film on the side of empiricism, and horror film and fantasy film on the side of transcendentalism. However, there are numerous well-known examples of science fiction horror films, epitomized by such pictures as Frankenstein and Alien.

The visual style of science fiction film can be characterized by a clash between alien and familiar images. This clash is implemented when alien images become familiar, as in A Clockwork Orange, when the repetitions of the Korova Milkbar make the alien decor seem more familiar.[1] As well, familiar images become alien, as in the films Repo Man and Liquid Sky.[2] For example, in Dr. Strangelove, the distortion of the humans make the familiar images seem more alien.[3] Finally, alien and familiar images are juxtaposed, as in The Deadly Mantis, when a giant praying mantis is shown climbing the Washington Monument.

Cultural theorist Scott Bukatman has proposed that science fiction film allows contemporary culture to witness an expression of the sublime, be it through exaggerated scale, apocalypse or transcendence.

Science fiction films appeared early in the silent film era, typically as short films shot in black and white, sometimes with colour tinting. They usually had a technological theme and were often intended to be humorous. In 1902, Georges Méliès released Le Voyage dans la Lune, often considered the first sci fi movie and a film that used early trick photography effects to depict a spacecraft’s journey to the moon. Several films merged the science-fiction and horror genres, such as Frankenstein (1910), a film adaptation of Mary Shelley's novel, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1912). A longer science fiction film, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1916), was based on Jules Verne’s novel. In the 1920s, European filmmakers tended to use science fiction films for prediction and social commentary, as can be seen in German films such as Metropolis (1927) and Frau im Mond (1929).

In the 1930s, there were several big budget science fiction films, notably Just Imagine (the first feature length science fiction film by a US studio), the US-made films King Kong (1933) and Lost Horizon (1936) and the British-made Things to Come (1936). Starting in 1934, a number of science fiction comic strips were adapted as serials, notably Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, both starring Buster Crabbe. These serials, and the comic strips they were based on, helped fix in the mind of the US public the idea that science fiction was juvenile and absurd, and led to the common description of science fiction as "that crazy Buck Rogers stuff". After 1936, no more big budget science fiction films were produced until 1950's Destination Moon, the first color film.

During the 1950s, the science fiction film became a popular genre with American audiences, leading to an increase in film production.[4] Public interest in space travel and new technologies revived. While many 1950s science-fiction films were still low-budget B movies, there were several successful films with larger budgets and impressive special effects. Some of the many B movies are also still of interest today. There was a close connection between many films in the science fiction genre and the monster movie, in, for example, Them!, The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, and The Blob.

Ray Harryhausen began to use stop-motion animation to create special effects for films.

There were relatively few science fiction films in the 1960s, but some of the films transformed science fiction cinema. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) brought new realism to the genre, with its groundbreaking visual effects and realistic portrayal of space travel and influenced the genre with its epic story and transcendent philosophical scope. Other 1960s films included Planet of the Apes (1968) and Fahrenheit 451 (1966), which provided social commentary, and the campy Barbarella (1968), which explored the sillier side of earlier science fiction. Jean-Luc Godard's French "new wave" film Alphaville (1965) posited a futuristic Paris commanded by an artificial intelligence which has outlawed all emotion.

Another influential science fiction film of the 1960s, though it was never produced, was Satyajit Ray's The Alien, a story about a boy in Bengal befriending an alien. After production of the film was cancelled, the script became available throughout America in mimeographed copies, and may have served as inspiration for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982).[5][6]

The era of manned trips to the moon in the 1970s saw a resurgence of interest in the science fiction film. Andrei Tarkovsky’s slow-paced Solaris (1972) had visuals and a philosophic scope reminiscent of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Science fiction films from the early 1970s explored the theme of paranoia, in which humanity is depicted as under threat from ecological or technological adversaries of its own creation, such as Silent Running (ecology), Westworld (man vs. robot), THX 1138 (man vs. the state), and Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (threat of brainwashing). Conspiracy thriller films of the 1970s included Soylent Green and Futureworld. The science fiction comedies of the 1970s included Woody Allen's Sleeper and John Carpenter's Dark Star.

Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, both released in 1977 , were box-office hits that brought about a huge increase in science fiction films. In 1979, Star Trek: The Motion Picture brought the television series to the big screen for the first time. It was also in this period that The Walt Disney Company released many science fiction films for family audiences such as The Island at the Top of the World, Escape to Witch Mountain, The Black Hole, Flight of the Navigator, and Honey, I Shrunk The Kids. Ridley Scott's films, such as Alien and Blade Runner, along with James Cameron's The Terminator, presented the future as dark, dirty and chaotic, and depicted aliens and androids as hostile and dangerous. In contrast, Steven Spielberg's E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, one of the most successful films of the 1980s, presented aliens as benign and friendly.

The big budget adaptations of Frank Herbert's Dune, Alex Raymond's Flash Gordon and Arthur C. Clarke's sequel to 2001, 2010, were box office duds that dissuaded producers from investing in science fiction literary properties. Disney's Tron turned out to be a moderate success. The strongest contributors to the genre during the second half of the 1980s were James Cameron and Paul Verhoeven with The Terminator and RoboCop entries. Robert Zemeckis' 1985 film Back to the Future and its sequels were critically praised and became box office successes, let alone international phenemenons. James Cameron's 1986 sequel to Alien, Aliens, was very different to the original film, falling more into the action/sci-fi genre, it was both a critical and commercial success and Sigourney Weaver was nominated for Best Actress in a Leading Role at the Academy Awards. The Japanese anime film Akira (1988) also had a big influence outside Japan when released.

In the 1990s, the emergence of the world wide web and the cyberpunk genre spawned several movies on the theme of the computer-human interface, such as Total Recall (1990), The Lawnmower Man (1992), and The Matrix (1999). Other themes included disaster movies (e.g., Armageddon and Deep Impact both from 1998), alien invasion (e.g., Independence Day from 1996) and genetic experimentation (e.g., Jurassic Park from 1993 and Gattaca from 1997).

As the decade progressed, computers played an increasingly important role in both the addition of special effects (thanks to Terminator 2:Judgment Day, and Jurassic Park) and the production of films. As software developed in sophistication it was used to produce more complicated effects. It also enabled filmmakers to enhance the visual quality of animation, resulting in films such as Ghost in the Shell (1995) from Japan, and The Iron Giant (1999) from the US.

During the first decade of the 2000s, superhero films abounded, as did earthbound SF such as the Matrix trilogy. In 2005, the Star Wars sextet was completed with the darkly-themed Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith. Science-fiction also returned as a tool for political commentary in films such as A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Minority Report, Sunshine, and Children of Men. J.J. Abrams's "Star Trek", released in 2009, would be an example of a critically acclaimed sci-fi film.

Science fiction films are often speculative in nature, and often include key supporting elements of science and technology. However, as often as not the "science" in a Hollywood science fiction movie can be considered pseudo-science, relying primarily on atmosphere and quasi-scientific artistic fancy than facts and conventional scientific theory. The definition can also vary depending on the viewpoint of the observer.[citation needed]

Many science fiction films include elements of mysticism, occult, magic, or the supernatural, considered by some to be more properly elements of fantasy or the occult (or religious) film.[citation needed] This transforms the movie genre into a science fantasy with a religious or quasi-religious philosophy serving as the driving motivation. The movie Forbidden Planet employs many common science fiction elements, but the film carries a profound message - that the evolution of a species toward technological perfection (in this case exemplified by the disappeared alien civilization called the "Krell") does not ensure the loss of primitive and dangerous urges.[citation needed] In the film this part of the primitive mind manifests itself as monstrous destructive force emanating from the freudian subconscious, or "Id".

Some films blur the line between the genres, such as movies where the protagonist gains the extraordinary powers of the superhero. These films usually employ a quasi-plausible reason for the hero gaining these powers.[citation needed]

Not all science fiction themes are equally suitable for movies. In addition to science fiction horror, space opera is most common.[citation needed] Often enough, these films could just as well pass as westerns or World War II movies if the science fiction props were removed.[citation needed] Common motifs also include voyages and expeditions to other planets, and dystopias, while utopias are rare.[citation needed]

Film theorist Vivian Sobchack argues that science fiction films differ from fantasy films in that while science fiction film seeks to achieve our belief in the images we are viewing, fantasy film instead attempts to suspend our disbelief. The science fiction film displays the unfamiliar and alien in the context of the familiar. Despite the alien nature of the scenes and science fictional elements of the setting, the imagery of the film is related back to mankind and how we relate to our surroundings. While the sf film strives to push the boundaries of the human experience, they remain bound to the conditions and understanding of the audience and thereby contain prosaic aspects, rather than being completely alien or abstract.[citation needed]

Genre films such as westerns or war movies are bound to a particular area or time period. This is not true of the science fiction film. However there are several common visual elements that are evocative of the genre. These include the spacecraft or space station, alien worlds or creatures, robots, and futuristic gadgets. More subtle visual clues can appear with changes the human form through modifications in appearance, size, or behavior, or by means a known environment turned eerily alien, such as an empty city.[citation needed]

While science is a major element of this genre, many movie studios take significant liberties with what is considered conventional scientific knowledge. Such liberties can be most readily observed in films that show spacecraft maneuvering in outer space. The vacuum should preclude the transmission of sound or maneuvers employing wings, yet the sound track is filled with inappropriate flying noises and changes in flight path resembling an aircraft banking. The film makers assume that the audience will be unfamiliar with the specifics of space travel, and focus is instead placed on providing acoustical atmosphere and the more familiar maneuvers of the aircraft.

Similar instances of ignoring science in favor of art can be seen when movies present environmental effects. Entire planets are destroyed in titanic explosions requiring mere seconds, whereas an actual event of this nature would likely take many hours.

The role of the scientist has varied considerably in the science fiction film genre, depending on the public perception of science and advanced technology.[citation needed] Starting with Dr. Frankenstein, the mad scientist became a stock character who posed a dire threat to society and perhaps even civilization. Certain portrayals of the "mad scientist", such as Peter Sellers's performance in Dr. Strangelove, have become iconic to the genre.[citation needed] In the monster movies of the 1950s, the scientist often played a heroic role as the only person who could provide a technological fix for some impending doom. Reflecting the distrust of government that began in the 1960s in the U.S., the brilliant but rebellious scientist became a common theme, often serving a Cassandra-like role during an impending disaster.

The concept of life, particularly intelligent life, having an extraterrestrial origin is a popular staple of science fiction films. Early films often used alien life forms as a threat or peril to the human race, where the invaders were frequently fictional representations of actual military or political threats on Earth. Later some aliens were represented as benign and even beneficial in nature in such films as Escape to Witch Mountain, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, "Koi Mil Gaya", and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Aliens in contemporary films are still often depicted as hostile, however, such as those in the Alien series of films.

In order to provide subject matter to which audiences can relate, the large majority of intelligent alien races presented in films have an anthropomorphic nature, possessing human emotions and motivations. Often they will embody a particular human stereotype, such as the barbaric warriors, scientific intellectuals, or priests and clerics.[citation needed] They will frequently appear to be nearly human in physical appearance, and communicate in a common Earth tongue, with little trace of an accent. Very few films have tried to represent intelligent aliens as something utterly different from human kind (e.g. Solaris).[citation needed]

A frequent theme among science fiction films is that of impending or actual disaster on an epic scale. These often address a particular concern of the writer by serving as a vehicle of warning against a type of activity, including technological research. In the case of alien invasion films, the creatures can provide as a stand-in for a feared foreign power.

Disaster films typically fall into the following general categories:[citation needed]

While monster films do not usually depict danger on a global or epic scale, science fiction film also has a long tradition of movies featuring monster attacks. These differ from similar films in the horror or fantasy genres because science fiction films typically rely on a scientific (or at least pseudo-scientific) rationale for the monster's existence, rather than a supernatural or magical reason. Often, the science fiction film monster is created, awakened, or "evolves" because of the machinations of a mad scientist, a nuclear accident, or a scientific experiment gone awry. Typical examples include The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), the Godzilla series of films.

The core mental aspects of what makes us human has been a staple of science fiction films, particularly since the 1980s. Blade Runner examined what made an organic-creation a human, while the RoboCop series saw an android mechanism fitted with the brain and reprogrammed mind of a human to create a cyborg. The idea of brain transfer was not entirely new to science fiction film, as the concept of the "mad scientist" transferring the human mind to another body is as old as Frankenstein.

Films such as Total Recall have popularized a thread of films that explore the concept of reprogramming the human mind. The theme of brainwashing in several films of the sixties and seventies including A Clockwork Orange and The Manchurian Candidate coincided with secret real-life government experimentation during Project MKULTRA. Voluntary erasure of memory is further explored as themes of the films Paycheck and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. The anime series Serial Experiments Lain also explores the idea of reprogrammable reality and memory.

The idea that a human could be entirely represented as a program in a computer was a core element of the film Tron. This would be further explored in the film version of The Lawnmower Man, and the idea reversed in Virtuosity as computer programs sought to become real persons. In the Matrix series, the virtual reality world became a real world prison for humanity, managed by intelligent machines. In eXistenZ, the nature of reality and virtual reality become intermixed with no clear distinguishing boundary.

Robots have been a part of science fiction since the Czech playwright Karel Čapek coined the word in 1921. In early films, robots were usually played by a human actor in a boxy metal suit, as in The Phantom Empire, although the female robot in Metropolis is an exception. The first depiction of a sophisticated robot in a US film was in The Day the Earth Stood Still. Over the last several decades, robots in films have been depicted as having increasingly advanced capabilities, including artificial intelligence.[citation needed] In films, robots are often depicted as humanoid-looking machines that walk stiffly and speak with a flat affect.[citation needed]

Robots in films are often sentient and sometimes sentimental, and they have filled a range of roles in science fiction films. Robots have been supporting characters, such as Robby the Robot in Forbidden Planet, sidekicks (e.g., C-3PO and R2-D2 from Star Wars), and extras, visible in the background to create a futuristic setting. As well, robots have been formidable movie villains or monsters (e.g., the robot Box in the 1976 film Logan's Run. In some cases, robots have even been the leading characters in science fiction films; in the 1982 film Blade Runner, many of the characters are bioengineered android "replicants".

One popular theme in science fiction film is whether robots will someday replace humans, a question raised in the film adaptation of Isaac Asimov's I, Robot, or whether intelligent robots could develop a conscience and a motivation to take over or destroy the human race (as depicted in The Terminator).

The concept of time travel—travelling backwards and forwards through time—has always been a popular staple of science fiction film and science fiction television series. Time travel usually involves the use of some type of advanced technology, such as H. G. Wells' classic The Time Machine, or the commercially successful 1980s-era Back to the Future trilogy. Other movies, such as the Planet of the Apes series, explained their depictions of time travel by drawing on physics concepts such as the Special relativity phenomenon of time dilation (which could occur if a spaceship was travelling near the speed of light). Some films show time travel not being attained from advanced technology, but rather from an inner source or personal power, such as the 2000s-era films Donnie Darko and The Butterfly Effect.

More conventional time travel movies use technology to bring the past to life in the present, or in a present that lies in our future. The movie Iceman (1984) told the story of the reanimation of a frozen Neanderthal. The movie Freejack (1992) shows time travel used to pull victims of horrible deaths forward in time a split-second before their demise, and then use their bodies for spare parts.

A common theme in time travel movies is the paradoxical nature of travelling through time. In the French New Wave film La Jetée (1962), director Chris Marker depicts the self-fulfilling aspect of a person being able to see their future by showing a child who witnesses the death of his future self. La Jetée was the inspiration for Twelve Monkeys, (1995) director Terry Gilliam's film about time travel, memory, and madness. The Back to the Future series goes one step further and explores the result of altering the past, while in Star Trek: First Contact (1996) the crew must rescue the Earth from having its past altered by time-travelling cyborgs.

The science fiction film genre has long served as a useful vehicle for "safely" discussing controversial topical issues and often providing thoughtful social commentary on potential unforeseen future issues. Presentation of issues that are difficult or disturbing for an audience, can be made more acceptable when they are explored in a future setting or on a different, earth-like world. The altered context can allow for deeper examination and reflection of the ideas presented, with the perspective of a viewer watching remote events. Most controversial issues in science fiction films tend to fall into two general story lines, Utopian or dystopian. Either a society will become better or worse in the future. Because of controversy, most science fiction films will fall into the dystopian film category rather than the Utopian category.

The type of commentary and controversy presented in a science fiction film often illustrated the particular concerns of the period in which they were produced. Early science fiction films expressed fears about automation replacing workers and the dehumanization of society through science and technology. Later films explored the fears of environmental catastrophe or technology-created disasters, and how they would impact society and individuals (i.e Soylent Green).

The monster movies of the 1950s—like Godzilla (1954)—served as stand-ins for fears of nuclear war, communism and views on the cold war.[citation needed] In the 1970s, science fiction films also became an effective way of satirizing contemporary social mores with Silent Running and Dark Star presenting hippies in space as a riposte to the militaristic types that had dominated earlier films.[citation needed] Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange presented a horrific vision of youth culture, portraying a youth gang engaged in rape and murder, along with disturbing scenes of forced psychological conditioning serving to comment on societal responses to crime.

Logan's Run depicted a futuristic swingers utopia that practiced euthanasia as a form of population control and The Stepford Wives anticipated a reaction to the women's liberation movement. Enemy Mine demonstrated that the foes we have come to hate are often just like us, even if they appear alien.

Contemporary science fiction films continue to explore social and political issues. One recent example would be 2002's Minority Report, debuting in the months after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and focused on the issues of police powers, privacy and civil liberties in the near-future United States.

More recently, the headlines surrounding events such as the Iraq War, international terrorism, the avian influenza scare, and U.S. anti-immigration laws have found their way into the consciousness of contemporary filmmakers. The 2006 film V for Vendetta drew inspiration from controversial issues such as The Patriot Act and the War on Terror, while the futuristic science fiction thriller Children of Men (also 2006) commented on diverse social issues such as xenophobia, propaganda, and cognitive dissonance.

Lancaster University professor Jamaluddin Bin Aziz argues that as science fiction has evolved and expanded, it has fused with other film genres such as gothic thrillers and film noir. When science fiction integrates film noir elements, Bin Aziz calls the resulting hybrid form "future noir," a form which "... encapsulates a postmodern encounter with generic persistence, creating a mixture of irony, pessimism, prediction, extrapolation, bleakness and nostalgia." Future noir films such as Blade Runner, Twelve Monkeys, Dark City, and Children of Men use a protagonist who is "...increasingly dubious, alienated and fragmented", at once "dark and playful like the characters in Gibson’s Neuromancer", yet still with the "...shadow of Philip Marlowe..."

Future noir films that are set in a post-apocalyptic world "...restructure and re-represent society in a parody of the atmospheric world usually found in noir’s construction of a city — dark, bleak and beguiled." Future noir films often intermingle elements of the gothic thriller genre, such as Minority Report, which makes references to occult practices, and Alien, with its tagline ‘In space, no one can hear you scream’, and a space vessel, Nostromo, “that hark[s] back to images of the haunted house in the gothic horror tradition.” Bin Aziz states that films such as James Cameron’s The Terminator are a sub-genre of ‘techno noir’ that create "...an atmospheric feast of noir darkness and a double-edged world that is not what it seems."[7]

When compared to science fiction literature, science fiction films often rely less on the human imagination and more upon action scenes and special effect-created alien creatures and exotic backgrounds. Since the 1970s, film audiences have come to expect a high standard for special effects in science fiction films. In some cases, science fiction-themed films superimpose an exotic, futuristic setting onto what would not otherwise be a science-fiction tale. Nevertheless, some critically-acclaimed science fiction movies have followed in the path of science fiction literature, using story development to explore abstract concepts.

Jules Verne was the first major science fiction author to be adapted for the screen with Melies Le Voyage dans la Lune (1902) and 20,000 lieues sous les mers (1907), which used Verne's scenarios as a framework for fantastic visuals. By the time Verne's work fell out of copyright in 1950 the adaptations were treated as period pieces. His works have been adapted a number of times since then, including 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea in 1954, From the Earth to the Moon in 1958, and Journey to the Center of the Earth in 1959.

H. G. Wells has had better success with The Invisible Man, Things to Come and The Island of Doctor Moreau all being adapted during his lifetime with good results while The War of the Worlds was updated in 1953 and again in 2005, adapted to film at least four times altogether. The Time Machine has had two film versions (1961 and 2002) while Sleeper in part is a pastiche of Wells' 1910 novel The Sleeper Awakes.

With the drop-off in interest in science fiction films during the 1940s, few of the 'golden age' science fiction authors made it to the screen. A novella by John W. Campbell provided the basis for The Thing from Another World (1951). Robert A. Heinlein contributed to the screenplay for Destination Moon in 1950, but none of his major works were adapted for the screen until the 1990s: The Puppet Masters in 1994 and Starship Troopers in 1997. Isaac Asimov's fiction influenced the Star Wars and Star Trek films, but it was not until 1988 that a film version of one of his short stories (Nightfall) was produced. The first major motion picture adaptation of a full-length Asimov work was Bicentennial Man (1999) (based on the short stories "Bicentennial Man" and "The Positronic Man" co-written with Robert Silverberg), although 2004's I, Robot, a film loosely based on Asimov's book of short stories by the same name, drew more attention.

The adaptation of science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke's novel as 2001: A Space Odyssey won the Academy Award for Visual Effects and offered thematic complexity not typically associated with the science fiction genre at the time. Its sequel, 2010, was commercially successful but less highly regarded by critics. Reflecting the times, two earlier science fiction works by Ray Bradbury were adapted for cinema in the 1960s with Fahrenheit 451 and The Illustrated Man. Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five was filmed in 1971 and Breakfast of Champions in 1998.

Philip K. Dick's fiction has been used in a number of science fiction films, in part because it evokes the paranoia that has been a central feature of the genre. Films based on Dick's works include Blade Runner (1982), Total Recall (1990), Impostor (2001), Minority Report (2002), Paycheck (2003), and A Scanner Darkly (2006). These films are loose adaptations of the original story, with the exception of A Scanner Darkly, which is close to Dick's book.

Frank Herbert used his science fiction novels to explore complex[7] ideas involving philosophy, religion, psychology, politics and ecology, which have caused many of his readers to take an interest in these areas. The underlying thrust of his work was a fascination with the question of human survival and evolution. Herbert has attracted a sometimes fanatical fan base, many of whom have tried to read everything he wrote, fiction or non-fiction, and see Herbert as something of an authority on the subject matters of his books. Indeed such was the devotion of some of his readers that Herbert was at times asked if he was founding a cult,[8] something he was very much against.

There are a number of key themes in Herbert's work:

Frank Herbert carefully refrained from

offering his readers

formulaic answers to many of the questions he explored.

In the post-classic era, the most significant trend in noir crossovers has involved science fiction. In Jean-Luc Godard's Alphaville (1965), Lemmy Caution is the name of the old-school private eye in the city of tomorrow. The Groundstar Conspiracy (1972) centers on another implacable investigator and an amnesiac named Welles. Soylent Green (1973), the first major American example, portrays a dystopian, near-future world via a self-evidently noir detection plot; starring Charlton Heston (the lead in Touch of Evil), it also features classic noir standbys Joseph Cotten, Edward G. Robinson, and Whit Bissell. The movie was directed by Richard Fleischer, who two decades before had directed several strong B noirs, including Armored Car Robbery (1950) and The Narrow Margin (1952).[105]

The cynical and stylish perspective of classic film noir had a formative effect on the cyberpunk genre of science fiction that emerged in the early 1980s; the movie most directly influential on cyberpunk was Blade Runner (1982), directed by Ridley Scott, which pays evocative homage to the classic noir mode[106] (Scott would subsequently direct the poignant noir crime melodrama Someone to Watch Over Me [1987]). Scholar Jamaluddin Bin Aziz has observed how "the shadow of Philip Marlowe lingers on" in such other "future noir" films as Twelve Monkeys (1995), Dark City (1998), and Minority Report (2002).[107] Fincher's feature debut was Alien 3 (1992), which evoked the classic noir jail movie Brute Force.

Cronenberg's Crash (1996), an adaptation of the speculative novel by J. G. Ballard, has been described as a "film noir in bruise tones".[108] The hero is the target of investigation in Gattaca (1997), which fuses film noir motifs with a scenario indebted to Brave New World. The Thirteenth Floor (1999), like Blade Runner, is an explicit homage to classic noir, in this case involving speculations about virtual reality. Science fiction, noir, and anime are brought together in the Japanese films Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004), both directed by Mamoru Oshii, and the television series Noir (2001).[1

|

|

This article or section has

multiple issues. Please help improve the article or

discuss these issues on the talk page.

|

This article provides an overview of religious themes in science fiction.

Science fiction (SF) works often present explanations, commentary or use religious themes to convey a broader message. The use of religious themes in the SF genre varies from refutations of religion as primitive or unscientific, to creative explanations and new insights into religious experience and beliefs as a way of gaining new perspectives to the human condition (e.g. gods as aliens, prophets as time travelers, metaphysical or prophetic vision gained through technological means, etc. ). The genre of science fiction with respect to the religious thematic schemes can be seen as an open system that can unpack and/or deconstruct (often in a postmodern sense) traditionally closed religious works for example, the relationship between the closed and limited nature of the creation story of Genesis in opposition to the open and expansive nature of the film The Matrix.

As an exploratory medium, SF rarely takes religion at face value by simply accepting or rejecting it, though a simple rejection does tend to be the more common bias, particularly in golden age authors like Robert A. Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke, but even among these this refutation is only general, not universal. As with many topics in SF, when religious themes are presented they tend to be investigated very deeply. The reader is invited to step outside the conventional understanding of the subject and consider wider possibilities that are often relevant to everyday human experience. Since the genre of SF often deals with humanity’s understanding of itself in the face of great technological and social change -- most SF grapples with questions of a spiritual or religious nature. Consequently the significance of religious themes in SF cannot be understated.

In addition to considering theological or philosophical or ideologies directly or indirectly from a religious context, some fiction deals with these topics as portraying real religions such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Bahá'í Faith - see LDS fiction and Bahá'í Faith in fiction.

In the story "In partibus infidelium" ("In the Land of the Unbelievers") by Polish writer Jacek Dukaj, humanity makes contact with other space-faring civilizations, and Christianity - specifically, the Catholic Church - spreads far and wide. Humans become a minority among believers and an alien is elected as the Pope...

One of the consequences of assuming time travel to be possible is to open up the possibility of modern people traveling back to the time of Jesus Christ - and specifically, to the crucifixion. This raises complex moral and religious questions dealt with in very different ways by different writers.

Cyberpunk is a science fiction genre noted for its focus on "high tech and low life".[1] The name is a portmanteau of cybernetics and punk and was originally coined by Bruce Bethke as the title of his short story "Cyberpunk", published in 1983.[2] It features advanced science, such as information technology and cybernetics, coupled with a degree of breakdown or radical change in the social order.[3]

Cyberpunk plots often center on a conflict among hackers, artificial intelligences, and megacorporations, and tend to be set in a near-future Earth, rather than the far-future settings or galactic vistas found in novels such as Isaac Asimov's Foundation or Frank Herbert's Dune.[4] The settings are usually post-industrial dystopias but tend to be marked by extraordinary cultural ferment and the use of technology in ways never anticipated by its creators ("the street finds its own uses for things").[5] Much of the genre's atmosphere echoes film noir, and written works in the genre often use techniques from detective fiction.[6]

"Classic cyberpunk characters were marginalized, alienated loners who lived on the edge of society in generally dystopic futures where daily life was impacted by rapid technological change, an ubiquitous datasphere of computerized information, and invasive modification of the human body." - Lawrence Person[7]

Contents[hide] |

Primary exponents of the cyberpunk field include William Gibson, Neal Stephenson, Bruce Sterling, Pat Cadigan, Rudy Rucker, and John Shirley.[8]

Many influential films, such as Blade Runner and the Matrix trilogy can be seen as prominent examples of the cyberpunk style and theme.[4] Computer games, board games, and role-playing games, such as Cyberpunk 2020 and Shadowrun, often feature storylines that are heavily influenced by cyberpunk writing and movies. Beginning in the early 1990s, some trends in fashion and music were also labeled as cyberpunk. Cyberpunk is also featured prominently in anime,[9] Akira and Ghost in the Shell being among the most notable.[9]

Cyberpunk writers tend to use elements from the hard-boiled detective novel, film noir, and postmodernist prose to describe the often nihilistic underground side of an electronic society. The genre's vision of a troubled future is often called the antithesis of the generally utopian visions of the future popular in the 1940s and 1950s. Gibson defined cyberpunk's antipathy towards utopian SF in his 1981 short story "The Gernsback Continuum", which pokes fun at and, to a certain extent, condemns utopian science fiction.[13][14][15]

In some cyberpunk writing, much of the action takes place online, in cyberspace, blurring the border between actual and virtual reality. A typical trope in such work is a direct connection between the human brain and computer systems. Cyberpunk depicts the world as a dark, sinister place with networked computers dominating every aspect of life. Giant, multinational corporations have for the most part replaced governments as centers of political, economic, and even military power.

Protagonists in cyberpunk writing usually include computer hackers, who are often patterned on the idea of the lone hero fighting injustice, such as Robin Hood.[16] One of the cyberpunk genre's prototype characters is Case, from Gibson's Neuromancer.[17] Case is a "console cowboy", a brilliant hacker who betrays his organized criminal partners. Robbed of his talent through a crippling injury inflicted by the vengeful partners, Case unexpectedly receives a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be healed by expert medical care but only if he participates in another criminal enterprise with a new crew.

Like Case, many cyberpunk protagonists are manipulated, placed in situations where they have little or no choice, and although they might see things through, they do not necessarily come out any further ahead than they previously were. These anti-heroes—"criminals, outcasts, visionaries, dissenters and misfits"[18] call to mind the private eye of detective novels. This emphasis on the misfits and the malcontents is the "punk" component of cyberpunk.

Cyberpunk can be intended to disquiet readers and call them to action. It often expresses a sense of rebellion, suggesting that one could describe it as a type of culture revolution in science fiction. In the words of author and critic David Brin:

…a closer look [at cyberpunk authors] reveals that they nearly always portray future societies in which governments have become wimpy and pathetic …Popular science fiction tales by Gibson, Williams, Cadigan and others do depict Orwellian accumulations of power in the next century, but nearly always clutched in the secretive hands of a wealthy or corporate elite.[19]

Cyberpunk stories have also been seen as fictional forecasts of the evolution of the Internet. The earliest descriptions of a global communications network came long before the World Wide Web entered popular awareness, though not before traditional science-fiction writers such as Arthur C. Clarke and some social commentators such as James Burke began predicting that such networks would eventually form.[20]

The science-fiction editor Gardner Dozois is generally acknowledged as the person who popularized the use of the term "cyberpunk" as a kind of literature, although Minnesota writer Bruce Bethke coined the term in 1980 for his short story "Cyberpunk", which was published in the November 1983 issue of Amazing Science Fiction Stories.[21] The term was quickly appropriated as a label to be applied to the works of William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Pat Cadigan and others. Of these, Sterling became the movement's chief ideologue, thanks to his fanzine Cheap Truth. John Shirley wrote articles on Sterling and Rucker's significance.[22]

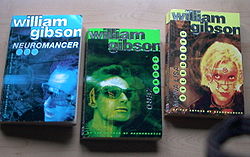

William Gibson with his novel Neuromancer (1984) is likely the most famous writer connected with the term cyberpunk. He emphasized style, a fascination with surfaces, and atmosphere over traditional science-fiction tropes. Regarded as ground-breaking and sometimes as "the archetypal cyberpunk work",[7] Neuromancer was awarded the Hugo, Nebula, and Philip K. Dick Awards. After Gibson's popular debut novel, Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988) followed. According to the Jargon File, "Gibson's near-total ignorance of computers and the present-day hacker culture enabled him to speculate about the role of computers and hackers in the future in ways hackers have since found both irritatingly naïve and tremendously stimulating".[23]

Early on, cyberpunk was hailed as a radical departure from science-fiction standards and a new manifestation of vitality.[24] Shortly thereafter, however, many critics arose to challenge its status as a revolutionary movement. These critics said that the SF "New Wave" of the 1960s was much more innovative as far as narrative techniques and styles were concerned.[25] Furthermore, while Neuromancer's narrator may have had an unusual "voice" for science fiction, much older examples can be found: Gibson's narrative voice, for example, resembles that of an updated Raymond Chandler, as in his novel The Big Sleep (1939).[24] Others noted that almost all traits claimed to be uniquely cyberpunk could in fact be found in older writers' works—often citing J. G. Ballard, Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, Stanislaw Lem, Samuel R. Delany, and even William S. Burroughs.[24] For example, Philip K. Dick's works contain recurring themes of social decay, artificial intelligence, paranoia, and blurred lines between objective and subjective realities, and the influential cyberpunk movie Blade Runner is based on one of his books. Humans linked to machines are found in Pohl and Kornbluth's Wolfbane (1959) and Roger Zelazny's Creatures of Light and Darkness (1968).

In 1994, scholar Brian Stonehill suggested that Thomas Pynchon's 1973 novel Gravity's Rainbow "not only curses but precurses what we now glibly dub cyberspace".[26] Other important predecessors include Alfred Bester's two most celebrated novels, The Demolished Man and The Stars My Destination,[27] as well as Vernor Vinge's novella True Names.[28]

Science-fiction writer David Brin describes cyberpunk as "the finest free promotion campaign ever waged on behalf of science fiction". It may not have attracted the "real punks", but it did ensnare many new readers, and it provided the sort of movement that postmodern literary critics found alluring. Cyberpunk made science fiction more attractive to academics, argues Brin; in addition, it made science fiction more profitable to Hollywood and to the visual arts generally. Although the "self-important rhetoric and whines of persecution" on the part of cyberpunk fans were irritating at worst and humorous at best, Brin declares that the "rebels did shake things up. We owe them a debt".[29]

Cyberpunk further inspired many professional writers who were not among the "original" cyberpunks to incorporate cyberpunk ideas into their own works, such as George Alec Effinger's When Gravity Fails. Wired magazine, created by Louis Rossetto and Jane Metcalfe, mixes new technology, art, literature, and current topics in order to interest today’s cyberpunk fans, which Paula Yoo claims "proves that hardcore hackers, multimedia junkies, cyberpunks and cellular freaks are poised to take over the world".[30]

As a wider variety of writers began to work with cyberpunk concepts, new sub-genres of science fiction emerged, playing off the cyberpunk label, and focusing on technology and its social effects in different ways. A prominent subgenre is "steampunk", which is set in an alternate history Victorian era that combines anachronistic techonology with cyberpunk's bleak film noir world view. The term was originally coined around 1987 as a joke to describe some of the novels of Tim Powers, James P. Blaylock, and K.W. Jeter, but by the time Gibson and Sterling entered the subgenre with their collaborative novel The Difference Engine the term was being used earnestly as well.[31]

Another subgenre is "biopunk" (cyberpunk themes dominated by biotechnology) from the early 1990s, a derivative style building on biotechnology rather than informational technology. In these stories, people are changed in some way not by mechanical means, but by genetic manipulation. Paul Di Filippo is seen as the most prominent biopunk writer, including his half-serious ribofunk. Bruce Sterling's Shaper/Mechanist cycle is also seen as a major influence. In addition, some people consider works such as Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age to be postcyberpunk.

The film Blade Runner (1982), adapted from Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, is set in 2019 in a dystopian future in which manufactured beings called replicants are slaves used on space colonies and are legal prey on Earth to various bounty hunters who "retire" (kill) them. Although Blade Runner was largely unsuccessful in its first theatrical release, it found a viewership in the home video market and became a cult film.[32] Since the movie omits the religious and mythical elements of Dick's original novel (e.g. empathy boxes and Wilbur Mercer), it falls more strictly within the cyberpunk genre than the novel does. William Gibson would later reveal that upon first viewing the film, he was surprised at how the look of this film matched his vision when he was working on Neuromancer. The film's tone has since been the staple of many cyberpunk movies, such as The Matrix (1999), which uses a wide variety of cyberpunk elements.

The number of films in the genre or at least using a few genre elements has grown steadily since Blade Runner. Several of Philip K. Dick's works have been adapted to the silver screen. The films Johnny Mnemonic[33] and New Rose Hotel,[34][35] both based upon short stories by William Gibson, flopped commercially and critically.

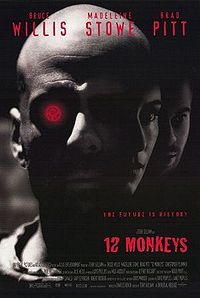

In addition, "tech-noir" film as a hybrid genre, means a work of combining neo-noir and science fiction or cyberpunk. It includes many cyberpunk films such as Blade Runner, The Terminator, 12 Monkeys.

| 12 Monkeys | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Terry Gilliam |

| Produced by | Charles Roven |

| Written by | Screenplay: David Peoples Janet Peoples Inspired by La Jetée: Chris Marker |

| Starring | Bruce

Willis Madeleine Stowe Brad Pitt Christopher Plummer |

| Music by | Paul Buckmaster |

| Cinematography | Roger Pratt |

| Editing by | Mick Audsley |

| Studio | Universal Pictures Atlas Entertainment Classico |

| Distributed by | North America: Universal Pictures Foreign: United International Pictures UK: PolyGram Filmed Entertainment |

| Release date(s) | United States: December 29, 1995 (limited) January 5, 1996 (wide) Australia: March 14, 1996 United Kingdom: April 19, 1996 New Zealand: May 10, 1996 |

| Running time | 130 min. |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $29.5 million |

| Gross revenue | $168.84 million |

12 Monkeys is a 1995 science fiction film directed by Terry Gilliam, inspired by the French short film La Jetée (1962), and starring Bruce Willis, Madeleine Stowe, Brad Pitt, and Christopher Plummer. The film depicts the world in 2035 as devastated by disease, forcing the human population to live underground. Convict James Cole (Willis) "volunteers" for time travel duty to gather information in exchange for prison release. When he first arrives in the past, Cole is arrested and locked up in a psychiatric hospital, where he meets Dr. Kathryn Railly (Stowe), a psychiatrist, and Jeffrey Goines (Pitt), the insane son of a world-renowned virologist.

After Universal Studios acquired the rights to remake La Jetée as a full-length film, David and Janet Peoples were hired to write the script. Under Terry Gilliam's direction, Universal granted the filmmakers a $29.5 million budget, and filming lasted from February to May 1995. The film was shot mostly in Philadelphia and Baltimore, where the story was set.

The film was released to critical praise and grossed approximately $168 million worldwide. Brad Pitt was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, and won a Golden Globe for his performance. The film also won and was nominated for various categories at the Saturn Awards.

Contents[hide] |

James Cole (Willis) is a convicted criminal living in a grim post-apocalyptic future. In 1996-1997, the Earth's surface was contaminated by a virus so deadly that it forced the surviving population to live underground. To earn a pardon, Cole allows scientists to send him on dangerous missions to the past to collect information on the virus, thought to be released by a terrorist organization known as the Army of the Twelve Monkeys. If possible, he is to obtain a pure sample of the original virus so a cure can be made. Throughout the film, Cole is troubled with recurring dreams involving a chase and a shooting in an airport.

On Cole's first trip, he arrives in Baltimore in 1990, not 1996 as planned. He is arrested and hospitalized in a mental institution on the diagnosis of Dr. Kathryn Railly (Stowe). There, he encounters Jeffrey Goines (Pitt), a fellow mental patient with animal rights and anti-consumerist leanings. Cole tries unsuccessfully to leave a voice mail on a number monitored by the scientists in the future. After a failed escape attempt, Cole is restrained and locked in a cell, but then disappears, returning to the future. Back in his own time, Cole is interviewed by the scientists, who play a distorted voice mail message which gives the location of the Army of the Twelve Monkeys and states that they are responsible for the virus. He is also shown photos of numerous people, including Goines. The scientists then send him back to 1996.

Cole kidnaps Railly and sets out in search of Goines, learning that he is founder of the Army of the Twelve Monkeys. When confronted, however, Goines denies any involvement with the virus and suggests that wiping out humanity was Cole's idea, originally broached at the asylum in 1990. Cole vanishes again as the police approach. After Cole disappears, Railly begins to doubt her diagnosis of Cole when she finds evidence that he is telling the truth. Cole, on the other hand, convinces himself that his future experiences are hallucinations, and persuades the scientists to send him back again. Railly attempts to settle the question of Cole's sanity by leaving a voice mail on the number he provided, creating the message the scientists played prior to his second mission. They both now realize that the coming plague is real, and make plans to enjoy the time they have left.

On their way to the airport, they learn that the Army of the Twelve Monkeys is a red herring; all the Army has done is delay traffic by releasing all the animals in the zoo. At the airport, Cole leaves a last message telling the scientists they are on the wrong track following the Army of the Twelve Monkeys, and that he will not return. He is soon confronted by Jose (Jon Seda), an acquaintance from his own time, who gives Cole a handgun and instructions to complete his mission. At the same time, Railly spots the true culprit behind the virus: Dr. Peters (David Morse), an assistant at the Goines virology lab. Peters is about to embark on a tour of several cities around the world, which matches the sequence (memorized by Cole) of viral outbreaks. Cole, while fighting through security, is fatally shot as he tries to stop Peters. As Cole dies in Railly's arms, she makes eye contact with a small boy – the young James Cole witnessing his own death; the scene that will replay in his dreams for years to come. Dr. Peters, safely aboard, sits down next to Jones (Carol Florence), one of the lead scientists in the future.

The genesis of 12 Monkeys came from executive producer Robert Kosberg, who had been a fan of the French short film La Jetée (1962). Kosberg persuaded the film's director, Chris Marker, to let him pitch the project to Universal Pictures, seeing it as a perfect basis for a full-length science fiction film. Universal reluctantly agreed to purchase the remake rights and hired David and Janet Peoples to write the screenplay.[1] Producer Charles Roven chose Terry Gilliam to direct because he believed the filmmaker's style was perfect for 12 Monkeys's nonlinear storyline and time travel subplot.[2] Gilliam had just abandoned a film adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities when he signed to direct 12 Monkeys.[3] The film also represents the second film for which Gilliam did not write or co-write the screenplay. Although he prefers to direct his own scripts, he was captivated by the Peoples' "intriguing and intelligent script. The story is disconcerting. It deals with time, madness and a perception of what the world is or isn't. It is a study of madness and dreams, of death and re-birth, set in a world coming apart."[2]

Universal took longer than expected to greenlight 12 Monkeys, although Gilliam had two stars (Bruce Willis and Brad Pitt) and a firm budget of $29.5 million (low for a Hollywood science fiction film). Universal's production of Waterworld (1995) had resulted in various cost overruns. To get 12 Monkeys greenlighted, Gilliam convinced Willis to lower his normal asking price.[4] Because of Universal's strict production incentives and his previous history with the studio on Brazil (1985), Gilliam received the right of final cut privilege.[5] The Writers Guild of America was also skeptical of the "inspired by" credit for La Jetée and Chris Marker.[6]

Gilliam's initial casting choices were Nick Nolte as James Cole and Jeff Bridges as Jeffrey Goines, but Universal objected.[3] Gilliam, who first met Bruce Willis while casting Jeff Bridges' role in The Fisher King (1991), believed Willis evoked Cole's characterization as being "somebody who is strong and dangerous but also vulnerable."[2] The actor had a trio of tattoos drawn onto his scalp and neck each day when filming: one that indicated his prisoner number, and a pair of barcodes on each side of his neck.

Gilliam cast Madeleine Stowe as Dr. Kathryn Railly because he was impressed by her performance in Blink (1994).[2] The director first met Stowe when he was casting his abandoned film adaptation of A Tale of Two Cities.[3] "She has this incredible ethereal beauty and she's incredibly intelligent," Gilliam reasoned. "Those two things rest very easily with her, and the film needed those elements because it has to be romantic."[2]

Gilliam originally believed that Brad

Pitt was not right for the role of Jeffrey Goines, but the casting

director convinced him otherwise.[3]

Pitt was cast for a relatively small salary, when he was still an "up

and coming" actor. By the time of 12 Monkeys' release, however,

Interview

with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles (1994), Legends of the Fall (1994), and Seven (1995) had been released, making

Pitt an A-list

actor, which drew greater attention to the film and boosted its

box-office standing.[5]

In Philadelphia, months before filming, Pitt spent weeks at Temple University's hospital, visiting

and studying the psychiatric ward to prepare for his role.[2]

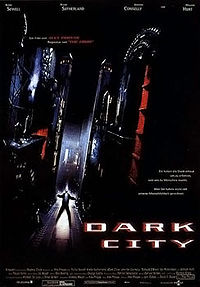

| Dark City | |

|---|---|

Dark City film poster |

|

| Directed by | Alex Proyas |

| Produced by | Alex Proyas Andrew Mason Michael De Luca Brian Witten |

| Written by | Alex Proyas David S. Goyer Lem Dobbs (screenplay) Alex Proyas (story) |

| Starring | Rufus

Sewell William Hurt Kiefer Sutherland Jennifer Connelly |

| Music by | Trevor Jones |

| Cinematography | Dariusz Wolski |

| Editing by | Dov Hoenig |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

| Release date(s) | February 27, 1998 |

| Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $27,000,000 |

| Gross revenue | $27,200,316 |

Dark City is a 1998 American science fiction film directed by Alex Proyas. The film was written by Proyas, Lem Dobbs, and David S. Goyer, and stars Rufus Sewell, William Hurt, Kiefer Sutherland, and Jennifer Connelly. While it was not a major box office success when released originally, it has subsequently developed a considerable cult fanbase among cineastes. Chicago Sun-Times film critic Roger Ebert is especially fond of the film, calling it the best of 1998.[1]

Contents[hide] |

John Murdoch (Rufus Sewell) awakens in a hotel bathtub, suffering from what seems to be amnesia. As he stumbles into his hotel room, he receives a telephone call from Dr. Daniel Schreber (Kiefer Sutherland), who urges him to flee the hotel from a group of men who are after him. During the telephone conversation, John discovers the corpse of a brutalised, ritualistically murdered woman, along with a bloody knife. Murdoch flees the scene, just as the figure, known as the Strangers, arrive at the room. Eventually he learns his real name, and finds his wife Emma (Jennifer Connelly). He is also sought by police inspector Frank Bumstead (William Hurt) for a series of murders, which he cannot remember. While being pursued by The Strangers, Murdoch discovers that he has psychokinetic powers like them and uses it to escape from them. Murdoch moves about the city, which experiences perpetual night. He sees people become comatose at midnight, with the cityscape being altered along with people's identities being changed at that time. Murdoch questions the dark urban environment and discovers through clues and interviews with his family that he was originally from a coastal town called Shell Beach. Attempts at finding a way out of the city to Shell Beach are hindered by lack of reliable information from everyone he meets. Meanwhile, the Strangers, disturbed by the presence of a human who also possesses tuning, their psychokinetic powers, inject one of their men, Mr. Hand (Richard O'Brien) with Murdoch's memories in an attempt to find him.

Murdoch eventually found Bumstead, who recognizes Murdoch's innocence and has his own questions about the nature of the dark city. They find and confront Dr. Schreber, who explains that the Strangers are endangered extraterrestrial parasites who use corpses as their hosts. Having a collective consciousness, the Strangers have been experimenting with humans to analyze the nature versus nurture concept of their human hosts in order to survive through memories. Schreber reveals Murdoch as an anomaly who inadvertently awoke during the midnight process when Schreber was in the middle of fashioning his identity as the murderer. The three men embark to find Shell Beach, which ultimately exists only as a billboard at the edge of the city. Frustrated, Murdoch tears through the wall, revealing a hole into outer space. The men are confronted by the Strangers, including Mr. Hand, who holds Emma hostage. In the ensuing fight, Bumstead, along with one of the Strangers, falls through the hole into space, revealing the city as an enormous space habitat surrounded by a force field.

The Strangers bring Murdoch to their home beneath the city and force Dr. Schreber to imprint Murdoch with their collective memory, believing Murdoch to be the final answer to their experiments. Schreber, having worked for the Strangers, betrays them instead by inserting false memories in Murdoch that use his memories and therefore the time of his entire life to train his tuning abilities. Murdoch awakens, fully realizing his abilities, frees himself and battles with the Strangers, defeating their leader Mr. Book (Ian Richardson) in a battle high above the city. After learning that "Emma" is gone and can't be restored, Murdoch utilizes his newfound powers through the Strangers' machine to create an actual Shell Beach by flooding the area within the force field with water and forming mountains and beaches. On his way to Shell Beach, Murdoch encounters Mr. Hand and informs him that the Strangers have been searching in the wrong place, the head, to understand humanity. Murdoch opens the door leading out of the city, and steps into sunlight that he fashioned. Beyond him is a dock, where he finds Emma, now with new memories and a new identity as Anna. Murdoch reintroduces himself as they walk to Shell Beach, beginning their relationship anew.

Director Alex Proyas wrote Dark City during 1990 and had the project associated initially with Walt Disney Pictures and then 20th Century Fox. The studios reneged on their agreements with Proyas due to their issues with the complexity of the story. New Line Cinema eventually accepted the project for production.[2] Before the final title of Dark City, the film had the working titles of Dark Empire and Dark World.[3] The film begins with a voice-over narration that reveals several major plot twists, which Proyas says was studio-imposed and "unnecessary".[4]

Director Alex Proyas first wrote the story of Dark City during 1991 as a detective story. The protagonist was a detective investigating a case that did not make logical sense, driving him insane as the evidence pointed to a larger, incomprehensible scheme. The detective was originally pursuing Murdoch, but Proyas considered the detective's perspective too analytical and changed it to the perspective of the man being chased for a more emotive perspective. The original plot was changed to the story of Eddie Walenski in the film, played by Colin Friels. Proyas was also inspired by science fiction stories of simulated reality that he read during his childhood. The director considered the result to be a Raymond Chandler story with a science fiction twist.[5]

The original ending for Dark City was bleak, with the Strangers claiming victory. Proyas, not liking the ending, decided to alter it to focus on the "individual's triumph" in an environment where individuality was being suppressed.[5]

Director Alex Proyas saw actor Rufus Sewell in several English television productions and a London stage show, and decided to cast the actor in the lead role of Dark City.[5]

Proyas cited actor Richard O'Brien, who portrays the Stranger Mr. Hand in Dark City, as the inspiration for the design of the Strangers themselves. Proyas was familiar with the actor's previous work and had discussions with O'Brien and other actors including Ian Richardson and David Wenham, who portrayed the Strangers to emulate O'Brien's presentation.[5]

The character Dr. Daniel P. Schreber was imagined originally by Proyas to be an older man. During the casting process, Proyas decided to have the doctor portrayed by Kiefer Sutherland, who the director believed would seem more motivated to escape from the Strangers if he were young and still had potential.[5]

Filming took place in Sydney, Australia.[5] Dark City has one of the shortest average shot lengths of a modern film; a film cut occurs in the film, on average, every 1.8 seconds.[6]

The film was inspired visually by German Expressionist films such as Metropolis (1927),[5] Nosferatu (1921) and M (1931).[2]

The morphing of the city landscape in Dark City was an idea by Proyas taken from production of his previous film, The Crow (1994). The film had a rooftop set in which smaller-scale buildings were moved around to create different backgrounds, accomplished by workers out of sight. Proyas recalled the implementation to use in Dark City. The director also included anachronisms in the film, such as a car from the 1980s driving by in the film, set in an earlier era. The city in the film was built from human memories, so the director wanted to blend together various elements to reflect the combination.[5]

The New Line Cinema Platinum Series contains one double-sided disc which include full-screen and wide-screen versions of the film. Other features include:

A director's cut of Dark City was released officially on DVD and Blu-ray Disc July 29, 2008. This version includes 15 minutes of additional footage, generally consisting of extended scenes with additional establishing shots and dialogue. In addition, the following major changes have been made:[7]

The Matrix was released one year after Dark City and was also filmed at Fox Studios in Sydney. Comparisons have been made between scenes from the movies, making note of similarities in both cinematography and atmosphere, as well as the plot.[8] Some stylistic similarities have also been noted to Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro's 1995 film The City of Lost Children.[9][10]

Fritz Lang's 1927 movie Metropolis was a major influence on the film, showing through the architecture, concepts of the baseness of humans within a metropolis, and general tone.[11] In one of the Documentary shorts featured on the Director's Cut, the influence of the early German films M and Nosferatu are mentioned.

The film bears strong resemblance to Frederik Pohl's acclaimed short story "The Tunnel Under the World", where an entire community is held captive by advertising researchers and have their memories of the day wiped clean every night as they sleep.[12] This thread is interwoven with similarities to other works: the random permutation of people's social identities is reminiscent of Jorge Luis Borges's short story "The Lottery in Babylon".[13]

One of the last scenes of the movie, in which buildings "restore" themselves, is strikingly similar to the last panel of the Akira manga. Proyas called the end battle a "homage to Otomo's Akira".[14]

The soundtrack for the film was released on February 24, 1998 on the TVT label.[15] It features music from the original score by Trevor Jones, and versions of the songs "Sway" and "The Night Has a Thousand Eyes" performed by singer Anita Kelsey. It also includes music by Hughes Hall from the trailer[16], as well as songs by Gary Numan, Echo & the Bunnymen, and Course of Empire that did not appear in the film.

Review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes gives it a "fresh" rating of 77 percent based on 77 reviews. Film critic Roger Ebert cited it as the best film of 1998.[1][17] In 2005, he included it on his "Great Movies" list.[18] Ebert uses it in his teaching, and also appears on a commentary track for the DVD.

The film was screened out of competition at the 1998 Cannes Film Festival.[19]

Dark City won the following awards:[20]

| Year | Award | Category |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Bram Stoker Award | Best Screenplay (tying with Gods and Monsters) |

| 1998 | Amsterdam Fantastic Film Festival — Silver Scream Award | |

| 1999 | Saturn Award | Best Science Fiction Film (tying with Armageddon) |

| 1999 | Brussels International Festival of Fantasy Film - Pegasus Audience Award | |

| 1999 | Film Critics Circle of Australia Award | Best Original Screenplay |

It was also nominated for the following awards: