Secret Agency in Mainstream Postmodern Cinema

Neal KingVirginia Polytechnic and Institute and State University

nmking@vt.edu

©

2008 Neal King.

All rights reserved.

- Among the most studied films of the last few decades are those that descend from the mid-century fiction of Philip Dick and his contemporaries, including Richard Condon (The Manchurian Candidate) and William Burroughs (Naked Lunch). These authors wrote during the Cold War scandal of the apparent "brain-washing" of U.S. soldiers by communists. In medical journal articles, Biderman and Lifton reported that military men had been coerced into confessing atrocities, and they helped to raise the specter of mind control, crystallizing fears of Big Brotherly rule that had been solidifying since the world war. As further news leaked of the Central Intelligence Agency's baroque attempts to counterprogram double-agents, sci-fi writers wove mind-control plots into parodies of spy novels. The agents in such tales believe their own covers and think that they are ordinary men until evidence of violent pasts disrupts their lives in colorful ways. In the most subversive stories, protagonists never know who they were or whom they might attack next.

- The setup, in which normal life masks one's status as a spy--a sort of hardboiled play on the monomyth--has drawn several filmmakers, who spin it into social satire. Consider a 1983 release by writer-director David Cronenberg. Tired of the banality programmed by the television station he runs, Max searches for "something harder." He samples recordings of torture called "Videodrome." The footage turns him on, and Max watches until he hallucinates a blend of video display, sex, and violence. But he soon learns that "Videodrome" is a mind control tool, wielded by fascists who induce Max to kill. He loses his grip on reality, appears to torture women, draws a gun from a hole in his gut and shoots men at work--all on orders from those who control him. At the end of Videodrome, Max blows his own brains out, television having poisoned his mind. In Max's postmodern story, local governance gives way to conspiracy, certainty to schizophrenia, and narrative realism to surreal subjectivity. The heroic agency sustained by Hollywood's classical alignment of spectators with successful, heterosexual protagonists is displaced by the penetration of bodies and minds. Max discovers that his status as agent-in-training has been kept so secret that neither he nor the audience knows about it until late in the film. He is a postmodern pawn.

- Ordinary-seeming citizens turn out to be unwitting secret agents, terrorists, and assassins in a series of North American films released over the last quarter century, including Blade Runner (1982), Videodrome (1983), Total Recall (1990), Naked Lunch (1991), The Long Kiss Goodnight (1996), Conspiracy Theory (1997), Dark City (1998), eXistenZ (1999), the three-film Matrix cycle (1999, 2003; see Figure 1 below), Imposter (2002), and A Scanner, Darkly (2006). In these movies, bourgeois protagonists discover secret lives of violence, engage with rebel groups, and then threaten and sometimes kill their own lovers. They escape ordinary routines and wrestle with over-socialization, media saturation, hampered agency, intensive surveillance, and the soul-draining effects of consumer capitalism. By discussing such films, I intend neither to nominate a genre nor to use them as reflections of the social world, but rather to consider the functions that production of and commentary on such films serve filmmakers, scholars, and perhaps others as well. The storytelling, which the 1950s brainwashing scandals indirectly inspired, have allowed filmmakers, analysts, and audiences to reconsider the status of authorship and agency in a postmodern world--in which subjects are commodities to be redefined for profit and prestige.

- There is no way to draw a clear line around the films named above. Scholars have included several of them in such overlapping sets as "mindfuck films" (Eig) and "puzzle films" (Elsaesser, Panek)--in some cases, claiming that Hollywood has undergone a large-scale, postmodern change. I have chosen the core of mind-job films simply by selecting those in which protagonists serve as unknowing agents of espionage. I study the derivation and correlates of this conceit in order to trace the origin of a postmodern segment of popular culture. Mind-job cinema engages postmodernity on the thematic level, and contemporary films result from an industrial context that has changed since the classical studio era of the 1930s and 1940s: for example, authors sign on to specific projects rather than to long-term employment by studios. One might thus presume that depictions of postmodernity in post-classical film arose with shifts in production--new modes of filmmaking (multinational hegemony, short-term contracting, the breakdown of genres and realism, etc.) and new patterns of storytelling. Indeed, the appearance of art-film styles of narration in mainstream, English-language feature film has led several scholars to posit a new narrative era, in which Hollywood's commitment to coherent, character-centered narrative drive has weakened. The general argument in such literature is that contemporary films are more likely than before to fracture their narratives into opaque spectacles, with thrills aplenty but scant import.

- For instance, a book-length study argues that postmodern cinema results from "a revulsion against tightly structured, formulaic, narrowly commercialized methods traditionally linked to the studio system" (Boggs and Pollard 7). That mode of production, of "classical Hollywood cinema" (Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson), includes attention to probabilistic and historical realism; coherent, clear plots that turn on decisions of white, heterosexual heroes; and editing/cinematography meant to disguise the artifice of narration and thus intensify emotional response. Critics have suggested that such cinema conveys "status quo ideals and messages" (Boggs and Pollard 5), and that the postmodern shift entailed critique and rejection of the modernity shored up by such ideology (6).

- Analysts argue for recent shifts in Hollywood storytelling, with the advent of the "psychological puzzle film" (Panek 65), with its (initially) unclear means of distinguishing protagonists' hallucinations from diegetic reality; of "post classical narration" (Thanouli), with its art-cinema trappings and addled protagonists; of big-budget action spectaculars (Davis and de los Rios), with their noisy set-pieces that crowd out character development; and of postmodern cinema (Beard, "Crisis of Classicism"), which recuperates cheery Hollywood from the pessimistic 1970's auteurist rebellion. Elsaesser also argues that "puzzle films" combine contemporary themes of psychic pathology (paranoia, schizophrenia) with the unreliable narration typical of post-classical film, and emerge from an industrial context in which filmmakers wish every film to provide "access for all" by meaning anything to anyone (37). Thus several analysts suggest that North American films have struck a sort of postmodern grand slam. In the postmodern era, these scholars argue, a significant chunk of storytelling has grown ambiguous in meaning, perhaps the better to serve the interests of the conglomerates that abjure widely shared critical views. These analyses suggest that especially fractured or polysemic storytelling also depicts elements distinct to postmodern life, grappling with the very forces that produce it: imbrications of virtual and real, electronic and fleshy, robotic and agentic; the inducement of disorientation and schizophrenia by corporate control. Thus might postmodern film be postmodern in all ways at once: in origin, in theme, and in narrative form. To assess the extent to which these forms coincide, I study the mind-job films from those angles.

- Analysis of structure reveals patterns in the plotting of secret-agent films. Mainstream artists, whether screenwriters or editing teams led by directors, tend to employ a four-act structure to feature film, in which regularly timed pauses emphasize protagonists' goals and/or changes of direction, in order to clarify unfolding plots (Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson).[1] Mind-job movies mostly use this structure to emphasize heroes' departures from normal life, confusion over identity, and crises brought by combat and isolation.[2]

- The Matrix and Total Recall, for example, both begin with a disaffected worker open to a new, more rebellious life. Each ends its opening act with the hero's break from the mundane: one unplugged from the titular "matrix" that imprisons his mind, the other driven from his home by a woman who turns out only to have posed as his wife ("your whole life is a lie," she tells him in Total Recall). Both heroes are rudely awakened to the fact that they have been brainwashed, their apparent normalcy all lies. Both begin to search for truths about their origins. The films' second acts introduce complications: one hero may be the foretold savior of the last colony of humankind, unplugged from the brainwashing matrix in order to free people from parasitic machines; the other may be a spy, also implanted (with false memories and a sham marriage to make the subterfuge more convincing) into a proletarian rebellion. These second acts end on moments of tension in which heroes wrestle with the competing possibilities that they are superhuman saviors, brainwashed dupes, or both ("What a mind job," says a skeptic of the savior prophecy, in The Matrix). The films' third acts play these possibilities off against each other as the oppressive rulers raise the stakes of the conflicts. Comrades and authorities provide competing testimonies, thus keeping heroes confused about who they really are. As is typical of Hollywood melodrama, third acts end on moments of crisis. In each case, a rebel mentor is captured or killed by an oppressive ruler; and it turns out that the deluded heroes were being used by secret police. "That's the best mind fuck yet," says the hero of Total Recall, who must escape another brainwashing in order to realize (what might be) his destiny. The hero of The Matrix must rescue his kidnapped mentor to fulfill his own. The fourth, climactic acts test heroes in the combat that suggests who they, and what their destinies, are. Both rescue people they love and appear to be foretold saviors after all, but both also know they were programmed by others to work their miracles. They may be heroic, but are hardly free in any liberal sense. Brainwashed to do good is brainwashed nonetheless; and they do not know which identities might be all their own, or whether there is such a thing. Indeed, the Matrix cycle saves its final revelation of the hero's purpose for the climax of its first sequel; then, as in Total Recall, he learns the dispiriting truth that his savior status was manufactured by oppressors to subvert rebellion (see Figure 2).

- Thus can mind-job films feature plots that are both parallel and clear: revelations of brainwashing inspire departures from normal life; competing hints at origins heighten confusion; escalating conflicts with oppressors lead to crises; and final combat allows heroes to rescue comrades and stake claims to destinies. Such plotting trains viewer attention on the characters' goals and their ongoing revision of and attempts to meet them. Though these stories depict confusion, they employ classical means to prevent it among viewers (at which both appear largely to have succeeded). Films with this plotting also released during the 1990s include The Long Kiss Goodnight and Dark City.

- As other examples of parallel plotting, consider two drug-novel adaptations, those of the Philip Dick's A Scanner Darkly and William Burroughs's Naked Lunch. Both concern addicts assigned to spy on loved ones. Though only one ends its first act with a traumatic event (Bill, the hero of Naked Lunch, gets high and accidentally shoots his wife), both end with heroes undercover, newly assigned to surveil drug peddlers. The second acts complicate assignments by hinting to the confused heroes how closely watched they are, without clarifying who they are. The protagonist of Naked Lunch shares a flat with an insectoid handler who directs his espionage. He makes new friends who are dead ringers for old ones and for the wife whom he has killed. His handler orders him to spy on those people but doesn't reveal how he came to spy in the first place. Who might pull the strings he cannot guess. The main characters of A Scanner Darkly share a house fitted with cameras and microphones that capture their drug use. We see the government's brainwashing process, by which the hero's mind is split and made to work for police so deep undercover that he does not realize that he is also one of the addicts who live there. He thus spies on his friends and on himself without realizing it. Both films end their second acts with newer, more focused assignments: One character is to spy closely on a woman who resembles his deceased wife, and the other resolves to spy more intently on the alter version of his own self.

- Thus, while the first acts disrupt ongoing routines with new missions, second ones complicate and then focus those missions on especially intimate spying. Third acts develop the goals clarified by the second acts without allowing heroes to meet them; the spies pursue questions of identity but find no final answers. In Naked Lunch, his handler breaks it to the hero that he was brainwashed and pre-programmed to kill his wife, who the handler claims was a counter spy ("An unconscious agent is an effective agent," he reassures the outraged hero). When friends try to talk him back to his normal life, this hero sends them away and drinks himself into a pit of despair. In A Scanner Darkly, the hero is troubled by the thought that a narc might live among his friends, but cannot see that it's him. Worried that he has lost his family forever and that betrayals abound in the drug war, he slips into an existential funk just as deep, staring into the camera at the end of the act. Thus do both films end third acts on notes of crisis. Heroes have tried but failed to learn who they are or where they are going, and fear that they will lose everyone they love. Those dark moments set up climactic pursuits.

- Fourth acts twist plots with final betrayals, send heroes into drug factories run by double agents, and foreground their lasting alienation and confusion. The narcotics agent of A Scanner Darkly winds up incarcerated in a drug-rehab center that serves as an illicit factory for drugs. He is so thoroughly brainwashed that he lives as a prisoner there without understanding that he's still being used to collect evidence of larger conspiracy. He secretes the blue flower that his handlers programmed him to obtain as evidence of drug production; but the film offers little hope that his mind will clear or mission end. The spy in Naked Lunch also visits a drug factory run by a man who pretends to cure addictions but instead fosters them for profit. There, the hero rescues the woman who resembles the wife whom he's killed, but then shoots her by accident as well. His story ends with a sense of ongoing tragedy and malaise. In neither film does the hero see a way out of the loop of loss, betrayal, and addictive madness. These stories are bleak, and they dwell on drug-addled, brainwashed confusion. But they both use Hollywood's four-act formula to keep mind-job stories as clear as possible (though neither sold many tickets). Heroes accept missions in their brainwashed states, later focus their spying on those closest to them, then become troubled by their lack of love and agency in those positions, and finally fail in their struggles for independence.[3]

- Other films with brainwashed spies that feature different plots also employ the Hollywood four-act structure to keep stories clear. The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and the 2004 remake offer minor variations on the same script. By the end of the second acts, heroes have learned that they were brainwashed. At the crisis-points that end third acts, delusional assassins murder women they love. Suicide, matricide, and salvation close both films. A more mainstream play on those parodies, Conspiracy Theory (1997) focuses on the romance and the danger that the brainwashed assassin poses to the woman he loves. Sunnier than the film it lampoons, Conspiracy Theory features no disturbing murders by heroic characters, but only the threat thereof. It ends happily for all but conspirators.

- We see more such classical structure if we look to the periphery of mind-job cinema. The obverse of the brainwashed-spy conceit is the story of a man who deludes himself that he is a spy when he (probably) is not. In A Beautiful Mind (2001) and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002) (both based on biographies), young professionals dream of stardom and sex. Heroes of these films perceive themselves to be recruited to Cold War espionage (code-breaking in one film, assassination in the other), both of them responding to their insecurities with women. In the second acts, both heroes mix their public lives as professionals (mathematician, game-show producer) with clandestine spying. In their third acts, both heroes try to square their delusions with cohabitation, and fail. Only in the climaxes do they forswear their lives as spies and attain some normalcy and romantic bliss. These films are more focused on professional and romantic success than are those in the mind-job core.[4] Other films that feature deluded operatives include Fight Club (1999) and Memento (2000), both of which offer narrative puzzles (what is diegetically real? what is a hero's hallucination?) and solve them in conventional fashion (climactic exposition specifies mental illness and the difference between hallucination and diegetic reality). Both rely on conventional four-act plotting to maintain clarity (see Bordwell [80] about the plot structure of Memento). The films neither mention spies nor draw from the stream running from the Condon/Burroughs/Dick novels, but they do suggest both the patterns that deluded-terrorist/detective stories can take, and their maintenance of conventions of clarity. The narrative shifts in these films do not make them postmodern.

- Indeed, claims about the postmodernity of shifts in storytelling may overstate the case. For instance, most of the elements of postmodern film noted by Boggs and Pollard (16) characterize decades of cinema rather than a postmodern period only: mass marketing, moral quagmires, film noir, and savage disorder--all present in Hollywood product since before World War II. Though mind-job films and other crime/sci-fi/horror cinema depict the immoral and insane, often in terms of deliberately puzzling narratives (such as whodunit detective stories that save revelations for last), mundane Hollywood storytelling remains as clear as ever. Intentional exceptions to the rule of narrative clarity in English language features are few. U.S. theaters have long showed European and Asian art films, with their own non-narrative modes; and Hollywood features have long depicted mentally unbalanced characters in ways that drew audiences to question lines between diegetic reality and hallucination (see, for instance, 1939's The Wizard of Oz). Examples of such cinema from the last two decades do not indicate postmodern shift in Hollywood cinema.[5]

- In any case, the plot patterns in the mind-job core suggest a common lineage, as though adapters of Condon, Burroughs, and Dick watched and read each other's works and developed the templates typical of generic production. It also suggests a commitment to classical Hollywood storytelling and the consumer-friendly clarity of plotting that it emphasizes, even if the protagonists tend to hallucinate and by doing so challenge audiences to learn each film's distinction (if any) between fantasy and diegetic reality. Most mind-job films supply viewers with enough information to arrive at plausible interpretations of plot events. (Exceptions come only from Cronenberg, whose screenplays, though generally clear and classically structured, leave open the possibilities that heroes never wake from their dreams.) Even when hallucination and reality blend, hegemonic conventions keep mind-job films from lapsing into the abstract self-consciousness of art-cinema narration. Those conventions are professional guides that filmmakers continue to take pride finding new ways to follow (Bordwell 51, 107). And viewers who hope to identify with heroes continue to demand that stories follow them as well (Eig).[6] Thus mind-job cinema is not particularly post-classical in its narrative form, though it is concerned with elements of postmodernity as themes.

- Fredric Jameson identifies "a whole mode of contemporary entertainment literature, which one is tempted to characterize as 'high tech paranoia', in which the circuits and networks of some putative global computer hook-up are narratively mobilized by labyrinthine conspiracies of autonomous but deadly interlocking and competing information agencies in a complexity often beyond the capacity of the normal reading mind" (80). Jameson roots conspiracy myth in the complexity of late capitalism, in which the growth of conglomerates (ruled by Byzantine legal codes but no obvious morals), breakdown of communities, and collisions of worldviews inspire general confusion. Industrial production has given way in the most developed world to consumer capitalism, as merchants pursue the unfettered advertisement and exchange that can most fully valorize their capital. Multinational corporations effect, via their intensive advertisement, "a prodigious expansion of capital into hitherto uncommodified areas [leading to the] colonization of Nature and the Unconscious" (78). What might have been "a space of praxis" becomes a no-man's land of disconnected places and times, or a set of ideas inserted into consciousness by powerful organizations. Jameson notes that forces of late capitalism control the very circuits of information that people use to imagine their worlds, blinding us to what we might learn from the stories that we tell. As an economic order, defended by the military that it mocks in its pop-culture parodies, the postmodern culture industry has shown that it can turn even criticism of rebellion against it into a commodity (56).

- One might expect characters to confront such a world in contemporary cinema, a world in which powerful but poorly understood forces govern the minds of high-tech professionals in the most subversive and intimate ways imaginable. Indeed, modernity appears as a theme in mind-job films, as protagonists' fears of being just like everyone else and too little the individuals of professional-worker ideals. Postmodernity in Hollywood cinema appears as the consumerism of urban renewal, in which old neighborhoods are plowed up and turned into ad-saturated consumer havens by shadowy conglomerates (the omnipresent advertising of Blade Runner--see Figure 3 below--and Total Recall, the manufactured communities of Dark City and The Matrix), only to be destroyed as heroes' mind-warps externalize in spectacular violence. Postmodernism also appears in the schizophrenia induced in Hollywood heroes, who decide that behind façades of shopping centers lie conspiracies too vast to comprehend. The tightening disciplines of postmodern life leave them feeling impotent, so they wade into public bloodbaths to redeem themselves. These films use the surrealist language of contemporary film to present schizophrenic, penetrative combat, suggesting a postmodern aesthetic of cyborg unreality.

- Three elements of postmodernity as theme thus bear brief discussion: blinkered perception, bodily violation, and hampered agency. Deluded about their pasts, mind-job heroes cannot trust their senses. As they buckle under psychic strain, the movies draw from sci-fi and horror cinema's arsenals of lurid imagery to convey confusion. In some cases, the environments around heroes alter as though with their moods. The Matrix films render fantasy in photo-realistic terms and shuttle characters through spatial displacements that make the architecture around them as confusing as any postmodern spaces. Total Recall features serpentine shots of vast interiors, viewed as if from the inside the hero's mind. The skyline of Dark City reshapes itself as buildings rise and fall, changing size and appearance in seconds. Though much of the style of mind-job cinema fits the model of "intensified continuity" in narrative film identified by Bordwell, and thus simply makes more frequent use of the most dramatic compositions, camera moves, and editing strategies of classical Hollywood, some hallucinatory scenes go further still, into the generic turf of science fiction. They execute virtual camera moves across vast spaces and through walls (as in the Matrix cycle and Total Recall), toying with the imbrications of electronic media with actual and psychic spaces. Sudden space-time displacements convey the heroes' fractured states of mind and the fall of the walls they have kept up between fantasy and reality. The Cronenberg films Videodrome, Naked Lunch, and eXistenZ offer prosthetic flesh-machines with erotic overtones, and symbolize fissured minds with penetrated bodies. Their heroes find themselves in new places without having traveled there by obvious means; they talk to strangers who seem to know them. Editing and physical effects allow audiences to share the heroes' queasy disorientation, one generally linked in the stories to the violations and bodies and minds.

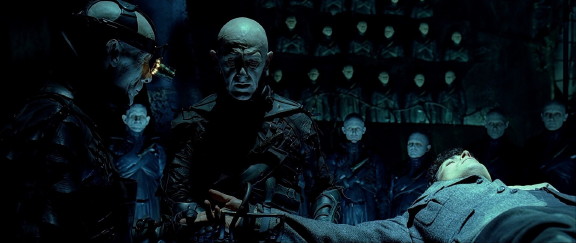

- The most obvious aesthetic development in mind-job cinema renders new relations between mind, flesh, and machine as penetrative violation. The hero of Videodrome develops a vaginal slit in his belly; he and other men slide videotapes and guns into the orifice and pull them out again, transformed but still deadly. The titular character of The Manchurian Candidate (2004) receives new programming through a needle into his brain; inhabitants of Dark City receive new personae through large syringes between their eyes; those of The Matrix do so through ports at the backs of their skulls. Inside the matrix, one has a "bug" crawl into his navel to keep track of him; and later a villain takes over the minds of other characters by plunging his virtual hand into their chests. The players of eXistenZ have ports of their own at the bases of their backs through which penile implants insert new worlds and identities.

- The penetrative tendencies of action cinema are realized most fully in scenes of mind-job combat. Shot by a "flesh gun," a villain in Videodrome dies by splitting from head to toe, organs exploding as his blood spouts. The brainwashing conspirators of Dark City die when their heads crack open and the insects within wriggle forth to expire. The colonialist of Total Recall loses his eyes to the vacuum of space as his head slowly pops. In Imposter, a cyborg assassin screams as cops eviscerate him and pull a weapon from his heart. Much of this assumes a sexual tone that implicates postmodern manhood. Others have written of the penetrative violence and wordplay of such mind-job films as eXistenZ and The Matrix (Freeland), Total Recall (Goldberg), and Videodrome (Beard, Artist as Monster; Shaviro), in most cases linking the bodily penetration to postmodern fantasies of compromised manhood. In his analysis of other science-fiction films, Byers suggests that allusions to male intimacy can play on a "pomophobia"--the sense that moral and physical perversion infiltrates the solid male subject of modernity (7). "The homophobic's paranoia about homosexual rape [expresses] a fear of violation of the masculine body that, in a heterosexual economy, sees itself as inviolable, as hard and sealed off rather than soft or opened" (15).[7]

- As mind job becomes "mind fuck" (as in Total Recall), men open their bodies and penetrate each other, claiming a perversely gendered space far from mundane life. Their domestic lives are phony set-ups and fall to violence and betrayal as battles compromise their bodies. Heroes are bound and/or brainwashed in the torture scenes of Imposter, The Matrix, The Long Kiss Goodnight, The Manchurian Candidate, Dark City (see Figure 4), Videodrome, Conspiracy Theory, and Total Recall. Most retaliate with penetrative assaults of their own. Some heroes escape with mere bullet wounds, beatings, and broken limbs, but the violation of a hero's body is nearly as foregone a conclusion as the mortification of a villain's.[8] These scenes involve face-offs between heroes and those who challenge their senses of themselves, burdening the violation with mind-job metaphors.

- Heroes, and the conspirators who mold their minds, direct much of the threat of violence against lovers. Brainwashed protagonists kill wives and (at least former) lovers in both versions of The Manchurian Candidate, The Long Kiss Goodnight, Naked Lunch and Total Recall, and eXistenZ, and have been programmed to do so in The Matrix and Dark City. Even in cases where heroes resist the urge to savage their families, they direct the violence elsewhere. The brainwashed hero of Dark City learns that he has been implanted with the impulses of a serial killer of women by the strangers who control him. But he claims, in the name of his love for the woman programmed to be his wife, a sense of personal autonomy. That formerly secret agency then manifests in mind-job form by laying waste to a city and slaughtering the strangers who have implanted their thoughts.[9]

- Entertaining an ideal of possessive individualism, with its promises of status and freedom, heroes seem to suffer the effects of pacifying surveillance, seductive advertisement, demanding romance, burdensome families, rule-bound employment, and addictive routine. They could seem to respond with violence as moral hygiene, as if to flush from their brains the codes of faceless conspiracies that govern their minds as well as their worlds. So does violence become one of the principal expressions of agency in mind-job cinema, rooted as it is in an apparent revulsion from intimacies of any kind. We should not presume that these films valorize agency of a modernist ideal, however. The thematic depiction appears to be more complex.

- For all of the fighting that heroes do, agency in its ideal form seems out of reach for most. Even the most professionally successful hero (of the peripheral film A Beautiful Mind) must learn to live with his phantoms, unable to will them away. Neo cannot save his world by fighting in The Matrix Revolutions. Asked why he endures beating after beating, knowing that he must die, he claims, "Because I choose to"; but only by relaxing and allowing his opponent to penetrate and kill him can Neo help to destroy his enemy, in a plan authored not by him but by the computer program that has directed his movements. His passive acquiescence, rather than a choice to stand tall against attack, saves the day. Dark City's John also triumphs in battle, but only after being programmed to do so by an ally with a syringe full of lethal thoughts. And the new world that John creates (including the name "John") is based not upon a life lived before his brainwashing but on the implanted programs instead. So must the hero of Total Recall worry about the possibility that he has won a battle by implanted design rather than by his own choosing. As protagonists shoot each other in eXistenZ, they must also wonder where virtual reality begins and ends, and thus whether the satisfying combat is of their own authorship or not. Other heroes kill themselves on the orders of implanted programming in Videodrome and Imposter. A testament to heroic agency, mind-job cinema is not.

- So mind-job films depict postmodern conditions, classically plotted. The remaining question bears on their origins. Does a movie that makes postmodernity its theme also arise from its unique mode of production?

- Mind-job

cinema issues from a small group of mainstream filmmakers (in the U.S.,

Australia, and Canada) who work with Cold War fantasies. Canadian

writer/director Cronenberg has been the most prolific translator,

having drafted a screenplay for Total Recall from one of

Dick's stories, adapted Burroughs's Naked Lunch, and made

two other films featuring the same elements (Videodrome

and eXistenZ). In his study of Cronenberg's cinema, The

Artist

as Monster, Beard celebrates this authorial lineage:

Cronenberg has always expressed his allegiance to the romantic-existentialist-modernist idea of the artist as heroic and transgressive explorer--explorer especially of the inner sources of transgression. His admiration especially for William Burroughs has always been expressed in these terms, and his attempts to emulate Burroughs have led him to create works which seek a direct, oneiric connection with unconscious instincts and associations. Videodrome is, along with Naked Lunch, certainly the best--most extreme and virtuosic--example of this phenomenon. The film's absolutely un-objective plunge into the realm of bodily disorder, identity chaos, bewildering transformation, and abjection signals a new commitment by Cronenberg to this principle of blind truth to the imagination, an embrace of fundamental disorientation as the price for a direct connection with the unconscious, and a discovery of a new path to the goal of artistic honesty. (123)

- This testament to the work that Cronenberg has done to adapt Burroughs raises the question of auteurism. A humanist theory of the origin of film narrative, auteurism has expanded from a friendly critical perspective to a corporate marketing pitch and the posture of many filmmakers who wish to build renown. The theory was invented by aspiring French filmmakers who celebrated the genius of the Hollywood directors (Hawks, Hitchcock, and Ford prominent among them); it explained how great films could be made within a profit-oriented industry. Decidedly modernist, auteurism celebrated the single artist's measure of control over work in the factory-like conditions of corporate Hollywood. It has also become the logic of block-buster era marketing. Distributors have found that writer-director, and producer-director "hyphenated" talent can make successful films, in part because the most popular names serve as product-differentiating brands in genre-film marketing (Baker and Faulkner, Flanagan). Auteurism's popularity has also grown with the development of the free-agent process of film-by-film deal-making among artists, which favors those authors who call attention to their skill at manipulating and pleasing viewers. The hope is that producers will hire an auteur as a safe bet to make a successful film. Thus do many parties maintain respective interests in the lauding of auteurist control over storytelling in film.

- The irony of auteurism as a scholarly theory of postmodern culture is that postmodernity as usually theorized undercuts the formations upon which auteurism depends: the stability of authorial subjects, the metaphor capacity of texts, and the shared meaning of mass cultural products. Consider the case of Blade Runner (1982). Adapted from a Philip Dick story, and making vivid the urban decay and corporate corruption of its setting, Blade Runner has assumed "the oxymoronic status of a canonical postmodern cultural artefact" among scholars (qtd. in Begley 188). The film tells the story of a cop assigned to slaughter renegade androids who have had human memories implanted so successfully that their corporate creators can market them as "more human than human." Fans of the film have long toyed with the notion that the cop is yet another android, brainwashed so thoroughly that he's bought his own cover as human and knows not what drives him. The film seems to hint at this with a momentary gleam in the hero's eye (and, in post-release versions, his dream of unicorns). At the end of the story, he takes an android as a lover and flees. Begley points out that scholars have embraced the metaphorical significance of Blade Runner's story in a way that works against their own theories of postmodern opacity. That is, some analysts interpret it both as a product of a dissimulating culture-industry and as a rich object for interpretation. On this conflict, Begley suggests that "it seems strangely mimetic to suppose" that a film such as Blade Runner "both represents and exemplifies postmodernism" (191). The argument that a film results from post-industrial shifts is a social-scientific one, usually paired in postmodern theory with the argument that films have lost much of their metaphorical import. This coheres as far as it goes, though it may exaggerate the change in Hollywood production (Bordwell 16, 189). Nevertheless, to argue in addition that Blade Runner director Ridley Scott and his screenwriters have achieved a vivid representation of the postmodern condition is to make a very different point, one in apparent conflict with the first. Those who analyze postmodernity as the decomposition of meaning, who also adhere to the modernist author as creator of metaphors that spectators may interpret, may be having their cake and eating it too. "Can narrative film mimetically reproduce postindustrial relations?" Begley asks rhetorically of such analysis. "Is Ridley Scott the author of postmodernity?" (191). Indeed, in view of the fracturing of meaning and authorship in postmodern theory, who would find value in such a claim to authority?

- Commentary celebrating the metaphorical significance of

postmodern film is not hard to come by: on Dark City

(Tryon); Terminator 2 (Byers); Videodrome

(Beard, Artist as Monster 125), Memento and

Conspiracy Theory (Boggs and Pollard).[10]

Consider

Boggs and Pollard on Blade Runner, among other

films:

While such movies do not fit conventional Hollywood formulas, they nonetheless stand at the critical edge of contemporary film culture today; their "postmodernity" equates with their graphic illumination of fundamental social and intellectual trends. (249)

This film's critical illumination of postmodernity, the authors argue, occurs in "the media-saturated public sphere" in which postmodern cinema in general "both appropriates and caricatures the antipolitical mood of the times while trivializing the major social problems that dominate the lives of ordinary citizens" (247). They thus provide the double argument typical of commentary on Blade Runner: it provides critical illumination, but also results from a production process that tends to diffuse the meaning of film. As Begley points out (191), the exceptional objects in such analysis tend to fit the eclectic standards of elite culture (high modernist in aesthetic, the work of reputable authors, and none too successful with the masses). The double status of such postmodern film is such that it both stands as product of an anti-political culture machine and (in some cases) allows for intensive interpretation of its insight into the postmodern condition. - What might have made this selective auteurism so popular? Begley suggests that such "postmodernist appropriation of Blade Runner rests on an ideal spectator who is very nearly an academic critic" (190).[11] I move beyond Begley's suggestion by adding that auteurist celebration of postmodern culture can also come in handy for filmmakers, whose careers might flourish if they can be branded auteurs. If the ideal spectator, in the celebration of postmodern culture, is nearly an academic critic, then perhaps the ideal filmmaker has the authority of a scholar. Ridley Scott has embraced the notion of the provocative, postmodern mind-job at the heart of the film he directed. He argues, in commentary attached to the pointedly labeled "Ridley Scott's Final Cut" home-video release of the film (2007), that Blade Runner's hero is indeed a replicant, programmed with the memories and skills of a human cop. By aligning with the notorious inference of the hero's nonhuman status, and taking credit for the implication, Scott asserts control over the film and the fans' responses. He dons the mantle of visionary that mimetic interpretation ascribes. Thus presented as intervention, not mere consumer product, Scott's work can seem both to result from and to provide critical commentary on the postmodern condition.

- The stories that filmmakers tell about making the films foreground authorial lineage and control. Jacobson and González chart the Hollywood development of The Manchurian Candidate in the wake of the success of Condon's novel. Cronenberg has stated that Videodrome was first inspired both by the career of Marshall McLuhan and by Cronenberg's experience watching late-night television (Cronenberg and Grünberg). It turned toward more political matters as he crafted his story for the science fiction and horror genres in which he works. On his DVD commentary, Cronenberg tells of the paranoia of Videodrome's star, who worried that a faceless, controlling "they" would destroy the film and its makers. Cronenberg says that he reassured those on the set that he, as writer/director, was in control. Thus might auteurism come in handy across a range of circumstances. On their DVD commentaries, production personnel note connections between these various works. The star of Videodrome connects it to the writing of Philip Dick; another actor, successful after starring in the Matrix films, provided the clout needed to get A Scanner Darkly made by agreeing to star in it; a screenwriter of Dark City notes (with distaste) resemblance between his story and the work of Cronenberg. Thus does a chain of storytelling connect Cold War jitters to Hollywood careers and craft. A small group of filmmakers, who work within their international, industrial network to exchange ideas and tell provocative stories, have mined postmodern ore from public interest in the brainwashing of soldiers and spies. The late-1950s appearance of reports of false confessions by U.S. soldiers raised discussion of "brainwashing." Several novels on the topic, popular films, and a stream of science fiction followed. Cronenberg and others read the novels, saw potentials for provocative filmmaking, and made a series of films that influenced other artists, resulting in more Philip Dick adaptations (Imposter, A Scanner Darkly, etc.) and parodies thereof (Conspiracy Theory and Shane Black's script for The Long Kiss Goodnight). The cyberpunk line of fiction influenced Australian Alex Proyas (Dark City) as well as the Wachowski brothers in the U.S. (The Matrix cycle). Copycatting of provocative stories became popular among filmmakers at the turn of the century, adding a more concrete motive to the larger trends postmodernity has wrought (e.g., widespread suspicion of intertwined corporate media and individual perception) (Wilson 93).

- Bordwell shows that filmmakers have long employed

attention-getting

devices within the framework of clearly-told stories (17) and do so

today in part to demonstrate their virtuosity (51). They work in a

distribution process so crowded that "product differentiation" serves

studios and storytellers (73):

Films aren't made just for audiences but for other filmmakers . . . a filmmaker can gain fame with fresh or elegant solutions to storytelling problems. . . . Prowess in craft yields not only professional satisfaction but also prestige, and perhaps a better job (107).

This appears to have worked for such well-known filmmakers as Frankenheimer (a television director who gained a reputation as a feature-film director with such early 1960's Cold War films as his 1962 version of The Manchurian Candidate), Cronenberg, the Wachowski brothers (The Matrix), and the authors of such peripheral films as A Beautiful Mind (which won Academy Awards) and Memento (which secured writer/director Christopher Nolan's status as a potent auteur in Hollywood, such that he now makes summer blockbusters). Thompson notes that, while the break-up of the monopolistic studios left artists to seek work on film-by-film bases rather than in long-term contracts, the day-to-day organization of the job remains largely the same--"coordinated from development to post-production via the use of a numbered continuity script [which guides the work of people who] still have a set of craft assumptions inherited from older generations" (346). Thus filmmakers flaunt plot twists and violence for the same reason they cleave to classical principles of storytelling. - In this loose network of artists we find the most immediate and concrete agency behind mind-job cinema--a group of filmmakers invested in tricky but clear storytelling, about heroes whose agency is hampered by the filmmaking beneficiaries of modernist celebration of authorship. Using the classical Hollywood model, filmmakers can boost their own status as auteurs by puncturing the delusions of the heroes whose stories they tell. Just as agency manifests in mind-job films as agonistic violence, often against loved ones, so does authorship appear as the showy mutilation of the traditional hero's subjectivity. These filmmakers play one agency off against another and show they are really in charge.

- Mind-job cinema may very well result from larger postmodern change; I note merely that we need not resort to theories of the collapse of Western narrative, the death of authorship, a fragmentation of mundane storytelling, or collective schizophrenia in order to explain the appearance of these stories. We have sufficient reason in the mundane workings of artistic networks in English-language, feature-film production. The root of mind-job cinema thus may or may not be postmodern production. But, either way and following Begley, I urge against having it all ways in our analyses. I do not see how mind-job movies can be both post-classically ambiguous and metaphorically clear, or be apolitical and bear insight into postmodern conditions. Indeed, the imputation of meaning to the mind-job movies, by their scholarly critics, by their fans, and by the filmmakers themselves (however career-serving those imputations might be), lend credence to the notion that storytelling by the international, Hollywood-dominated film industry is more classical and more modernist than not. For all of the schizophrenia and conspiratorial brainwashing depicted onscreen, these stories tell, in reasonably clear fashion, stories of people with postmodern problems. They slight neither clear progress nor character development for vapid nostalgia, violent spectacle, or brainwashed hallucination. Nor does such storytelling appear to respond to uniquely postmodern demand. Though a generation will have grown up on video screenings of Fight Club and The Matrix, mind-job films are not otherwise hits. These visions of compromised agency and restless violence seem unlikely to indicate mass sentiments or to shape their courses. The small size of audiences for most of these films suggests that we look elsewhere to explain patterns in the storytelling. Likewise, though Cronenberg tells stories that never specify diegetic reality, he is alone in that respect among makers of mind-job cinema, and does not indicate a larger trend. Postmodernism in Hollywood's storytelling may be sharply constrained by its commercial impulses.

- Changes in mass culture issue from the practices of (consumer capitalist) organizations, by the artists both employed and selfishly motivated to push cultural boundaries with "edgy" entertainment, loaded as that might be with nutty assassins and their mind-blowing violence. By splintering the psyches of their protagonists, filmmakers tout the reliability of their own craftsmanship, in service of careers in a labor market that maintains wholly modernist ideals of authorship.

|

| |

| Figure

1: Scene from The Matrix. Postmodernity taken literally, as body and agency compromised. © Warner Bros., 2008. Image from the author's personal collection. |

Mind-Job Plotting

|

| |

| Figure

1: Scene from Total Recall. Crisis ends the third act and leads to the climactic battles of the film. All appears to be lost as the hero sees double, confronted by the oppressive state with evidence that his personality is a scam implanted to manipulate him and destroy rebellion. © Lion's Gate, 2006. Image from the author's personal collection. |

Mind-Job Themes

|

| |

| Figure

3: Scene from Blade Runner. Postmodernity appears as theme in this confusing, ad-intensive cityscape. © Warner Brothers, 2008. Image from the author's personal collection. |

|

| |

| Figure

3: Scene from Dark City. Posthuman conspirators prepare to inject a controlling, collective personality into the skull of the bound hero. © New Line, 2008. Image from the author's personal collection. |

Mind-Job Production

Interdisciplinary

Studies

Virginia Polytechnic and Institute and State University

nmking@vt.edu

Talk Back

COPYRIGHT © 2008 Neal King. READERS MAY USE PORTIONS OF THIS WORK IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE FAIR USE PROVISIONS OF U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW. IN ADDITION, SUBSCRIBERS AND MEMBERS OF SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTIONS MAY USE THE ENTIRE WORK FOR ANY INTERNAL NONCOMMERCIAL PURPOSE BUT, OTHER THAN ONE COPY SENT BY EMAIL, PRINT OR FAX TO ONE PERSON AT ANOTHER LOCATION FOR THAT INDIVIDUAL'S PERSONAL USE, DISTRIBUTION OF THIS ARTICLE OUTSIDE OF A SUBSCRIBED INSTITUTION WITHOUT EXPRESS WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM EITHER THE AUTHOR OR THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS IS EXPRESSLY FORBIDDEN.

THIS ARTICLE AND OTHER CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE ARE AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE UNTIL RELEASE OF THE NEXT ISSUE. A TEXT-ONLY ARCHIVE OF THE JOURNAL IS ALSO AVAILABLE FREE OF CHARGE. FOR FULL HYPERTEXT ACCESS TO BACK ISSUES, SEARCH UTILITIES, AND OTHER VALUABLE FEATURES, YOU OR YOUR INSTITUTION MAY SUBSCRIBE TO PROJECT MUSE, THE ON-LINE JOURNALS PROJECT OF THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY PRESS.

Notes

1. Analysts (Bordwell, Staiger, and Thompson) have demonstrated that large numbers of Hollywood feature films adhere to classical principles of character-driven drama. Thompson shows that such films break their stories into sets of acts (usually four per 90-150" feature, rather than the three claimed by Syd Field in his famous 1979 text), which emphasize character traits at their conclusions. Filmmakers use stylistic flourishes to mark end points of dramatic acts, to inspire moments of contemplation, to emphasize changes of direction, and thus to clarify the unfolding stories and maintain viewer interest. By having characters redirect the courses of their action at such points and provide the audience with moments of reflection, feature films privilege those decisions as defining characteristics.

2. I use the term "hero" not as approbation or affirmation of agency but as shorthand for the character on whom the camera and story dwell. A hero is the character who spends at least as much time on screen as any other and whose personal trials receive as much attention as those of any other, and may not be the principal agent driving the plot.

3. This is not to say that all stories are equally plot-focused. The adaptation of A Scanner Darkly includes a few scenes that illustrate character rather than advance the surveillance plot or depict changes in those characters. The writer/director wishes not to be known for "by-the-book storytelling" (Johnson 340). In his commentary on the home-video release of the film, Linklater recounts studio pressure to cut the static scenes.

4. In a different direction, a peripheral cycle such as the Jason Bourne series (2002, 2004, 2007)--based on Robert Ludlum's spy novels--involves brain injury and amnesia, and a brief sequence during which a hero discovers that he was trained to do violence. But it does not depict the intrusion of spy memories into normal life, because the hero never has a normal life. Cop action movies with mind-job elements include the Robocop cycle (1987, 1990, 1993) and Demolition Man (1993), in which cop heroes are electronically brainwashed in order to prevent them from challenging lawless oppressors.

5. Berg excludes art films and the science fiction genre from his survey of "alternative" plotting because the former are defined as those primarily aimed at formal experimentation (12), and the latter "provides the motivation for and naturalizes" breaks in continuity (11). He rightly suggests that the best test of change in Hollywood storytelling comes from mainstream feature films outside of those sets.

6. Volker argues that reports of the death of traditional, reliable narration in mainstream feature films are greatly exaggerated. He advocates that we distinguish stories that merely confuse their audiences from those in which main characters mislead by narrating delusions or lies. By his standard, a film such as Fight Club has an unreliable narrator, whereas a hallucinatory film such as Naked Lunch does not. By its conclusion, as its narrator's head clears, Fight Club more rigidly distinguishes between the protagonist's hallucination and diegetic reality than Cronenberg ever does. Cronenberg has stated (in DVD commentary for Videodrome) that he does not mark hallucinations stylistically, because "they feel real" to those who experience them. But Cronenberg is alone in this approach among mind-job filmmakers. Eig suggests that a film that was postmodern not only in theme, but in narrative form as well, would do without the classical storytelling typical of films such as Fight Club.

7. Much of mind-job cinema violence follows the trend of contemporary crime movies, in which gory, penetrative combat accompanies puns about homosexuality and homosocial bonding. But these intimate violations transcend even the liberal standards of cop action bloodshed. In the cop movies that are peripheral to the mind-job cycle, sexual violence between men marks a space where men admit to their madness and love of antisocial action (King). So too, in mind-job cinema, where heroes join anarchic quests and revel in rebellious destruction.

8. The least violent film is A Scanner Darkly. It features the explosion of a man's head by gunfire but little other bloodshed. It is also the most depressive of the set, leaving its dazed hero incarcerated in a nearly somnambulant state at its conclusion, as if to suggest that, without violence, mind-job heroes cannot wake.

9. Peripheral films include such romantic comedies as True Lies (1994), Grosse Pointe Blank (1997), Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005), and War, Inc. (2008). The heroes are not deluded about their work as assassins, but their loved ones are, and heroes get stressed trying to integrate their lives. The films play with the threats that confused heroes pose to their lovers as they flee the constraints of consumer life. For instance, Grosse Pointe Blank arranges names and dialogue to represent the hero's anomie: his name is Mr. Blank; he repeats the schizophrenic's mantra ("It's not me") when he kills, hides behind dark glasses, and extorts psychotherapy with mocking threats of violence.

10. Consider this scholarly commentary on The Truman Show, a cousin of mind-job films in which an apparently ordinary man only realizes in middle age that his life has been choreographed by a television producer. The commentary demonstrates links between the purposes of film critics, postmodern scholars, and marketers of mainstream film:

While my own critical response to the film's artistic merit is no different than most critics' appraisal of it as a powerful indictment of rampant technology and rote consumerism or as a "thought-stirring parable about privacy and voyeurism" (Guthmann www.aboutfilm.com), the real critical value of The Truman Show lies in the boldness of its central concept and its self-reflexivity which provides an apt metacommentary on the New Hollywood situation.In the context of Kokonis's larger argument that Hollywood film has subordinated narrative and critical commentary to spectacle, this is a remarkable assessment of a postmodern film. The showy self-reflexivity of so many Hollywood authors serves in such analysis, paradoxically, as evidence that claims of hampered agency/authorship are valid. I suggest not that the makers of The Truman Show lack the insight that Kokonis attributes to them, but rather that such intensive interpretation undercuts his own larger argument about postmodern, postclassical Hollywood, and the way in which its storytelling has sacrificed its critical, interpretable edge.

11. Boggs and Pollard discuss the fate of film authorship in postmodern Hollywood, concluding with the paradox that recent change in production "simultaneously elevates and diminishes the status of auteur" (23), endowing them with "the aura of (postmodern) critical public intellectuals" (21). This is because directors can attain celebrity status and work as free agents but must submit to increasingly tight corporate control in order to have their projects funded.

Works Cited

Baker, Wayne E., and Robert R. Faulkner. "Role as Resource in the Hollywood Film Industry." The American Journal of Sociology 97.2 (1991): 279-309.

Beard, William. The Artist as Monster: The Cinema of David Cronenberg. Toronto: University of Toronto P, 2001.

---. "The Crisis of Classicism in Hollywood, 1967-77." S: European Journal for Semiotic Studies 10.1-2 (1998): 7-23.

Begley, Varun. "Blade Runner and the Postmodern: A Reconsideration." Literature/Film Quarterly 32.3 (2004): 186-92.

Berg, Charles Ramirez. "A Taxonomy of Alternative Plots in Recent Films: Classifying The 'Tarantino Effect'." Film Criticism 31.1/2 (2006): 5-61.

Biderman, Albert D. "Communist Attempts to Elicit False Confessions from Air Force Prisoners of War." Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 33.9 (1957): 616–25.

Blade Runner. Five-Disc Complete Collector's Edition. Dir. Ridley Scott. Perf. Harrison Ford. 1982. Blu-ray. Warner Bros. Entertainment, 2007.

Boggs, Carl, and Thomas Pollard. A World in Chaos: Social Crisis and the Rise of Postmodern Cinema. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2003.

Bordwell, David. The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. Berkeley: University of California P, 2006.

Bordwell, David, Kristin Thompson, and Janet Staiger. The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960. New York: Columbia UP, 1985.

Byers, Thomas B. "Terminating the Postmodern: Masculinity and Pomophobia." Modern Fiction Studies 41.1 (1995): 5-33.

Cronenberg, David, and Serge Grünberg. David Cronenberg. London: Plexus, 2006.

Dark City. Director's Cut. Dir. Alex Proyas. Perf. Rufus Sewell. 1998. Blu-ray. New Line Home Entertainment, 2008.

Davis, Robert, and Riccardo de los Rios. "From Hollywood to Tokyo: Resolving a Tension in Contemporary Narrative Cinema." Film Criticism 31.1/2 (2006): 157-72.

Eig, Jonathan. "A Beautiful Mind(Fuck): Hollywood Structures of Identity." Jump Cut: A review of contemporary media 46 (2003). July 2008 <http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc46.2003/eig.mindfilms/text.html>.

Elsaesser, Thomas. "The Mind-Game Film." Puzzle Films: Complex Storytelling in Contemporary Cinema. Ed. Warren Buckland. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 13-41.

Ferenz, Volker. "Fight Clubs, American Psychos and Mementos: The Scope of Unreliable Narration in Film." New Review of Film and Television Studies 3.2 (2005): 133-59.

Field, Syd. Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting. New York: Dell Pub. Co., 1979.

Flanagan, Martin. "The Hulk, an Ang Lee Film." New Review of Film and Television Studies 2.1 (2004): 19-35.

Freeland, Cynthia A. "Penetrating Keanu: New Holes but the Same Old Shit." The Matrix and Philosophy: Welcome to the Desert of the Real. Ed. William Irwin. Chicago: Open Court, 2002. 205-15.

Goldberg, Jonathan. "Recalling Totalities: The Mirrored Stages of Arnold Schwarzenegger." differences 4.1 (1992): 172-204.

Jacobson, Matthew Frye, and Gaspar González. What Have They Built You to Do?: The Manchurian Candidate and Cold War America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Jameson, Fredric. "Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism." New Left Review 146 (1984): 53-92.

Johnson, David T. "Directors on Adaptation: A Conversation with Richard Linklater." Literature/Film Quarterly 35.1 (2007): 338-41.

King, Neal. Heroes in Hard Times: Cop Action Movies in the U.S. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1999.

Kokonis, Michael. "Postmodernism, Hyperreality and the Hegemony of Spectacle in New Hollywood: The Case of The Truman Show." Gramma: Journal of Theory and Criticism 7.2 (2002).

Lifton, Robert J. "Chinese Communist 'Thought Reform': Confession and Re-Education of Western Civilians." Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 33.9 (1957): 626–44.

The Matrix. The Ultimate Matrix Collection. Dir. Andy and Larry and Wachowski. Perf. Keanu Reeves. 1999. Blu-ray. Warner Bros. Entertainment, 2008.

Panek, Elliot. "The Poet and the Detective: Defining the Psychological Puzzle Film." Film Criticism 31.1/2 (2006): 62-88.

Shaviro, Steven. The Cinematic Body. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota P, 1993.

Thanouli, Eleftheria. "Post-Classical Narration: A New Paradigm in Contemporary Cinema." New Review of Film and Television Studies 4.3 (2006): 183-96.

Thompson, Kristin. Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1999.

Total Recall. Dir. Paul Verhoeven. Perf. Arnold Schwarzenegger. 1990. Blu-ray. Lion's Gate Entertainment, 2006.

Tryon, Charles. "Virtual Cities and Stolen Memories: Temporality and the Digital in Dark City." Film Criticism 28.2 (2003): 42-62.

Wilson, George. "Transparency and Twist in Narrative Fiction Film." Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 64.1 (2006): 81-95.