Nobel laureate

Joseph Stiglitz, professor at Columbia University, told the media in

Singapore that the likelihood of the U.S. economy sliding back into

recession is "very, very high" in 2010. Stiglitz attributes this risk

to the lack of job creation as our so-called "V-shaped" recovery takes

place. Stiglitz argues that the U.S. economy must grow at 3% annually

in order to create enough jobs for the expanding workforce. The

probability that U.S. can sustain a 3% pace of recovery is low.

Interestingly, Stiglitz suggests that the federal government should

prepare another stimulus

package aimed at providing job growth. This third stimulus bill would

inevitably be wracked by the political pork which made the second $787

billion bill a complete waste of tax payer money and Congressional

effort. I agree with Stiglitz that the 'jobless' nature of this

recovery will not be a benign thing. There is no way that the U.S.

economy can increase productivity indefinitely without an expansion in

employment and the failure of job growth in the second half of 2010

will likely cause further recession.

With the withdrawal of

government spending and the increase in taxes we will likely see,

investment will only occur with an expansion of consumption. The

W-shaped recession is still a very possible scenario. Nevertheless, I

reject Stiglitz's idea that the government can just pass a bill each

time the economic situation looks to be worsening in order to forestall

a contraction. This tactic did not work in the spring of 2008, nor has

the current fiscal stimulus package done much for the monetary-driven

recovery we've seen thus far.

Disclosure: None

Stiglitz: The U.S. Will Crash Again Unless We Pass Even More

Stimulus

Once again, the U.S. economy

faces disaster should we not enact more stimulus. Joseph Stiglitz has

warned that the U.S. economy could contract again in the second half of

2010 without additional government stimulus.

Once again, the U.S. economy

faces disaster should we not enact more stimulus. Joseph Stiglitz has

warned that the U.S. economy could contract again in the second half of

2010 without additional government stimulus.

Canadian

Press:

"The likelihood of this slowdown is very, very high," Stiglitz told

reporters in Singapore. "There is a significant chance that the number

will be in the negative range." Stiglitz, a professor at Columbia

University, called on Washington to make more funds available to state

governments who face a drop in tax revenue.

The

U.S. economy, the world's largest, must grow at least 3 per cent to

create enough jobs for new entrants into the labour force, he said.

...

"If you don't prepare now, and the

economy turns out to be as weak as I think it's likely to be, then

you'll be in a very difficult position," he said.

Thing is, at the very least, shouldn't we first wait until the

majority of current stimulus is spent? The U.S. has barely done 30%

so far. The rallying dollar

probably doesn't expect much influence from Mr. Stiglitz

next year.

Stiglitz warns US economy may contract in second half of 2010, calls

for more stimulus

By Alex Kennedy

(CP)

–

Dec 20, 2009

SINGAPORE — Nobel Prize-winning economist

Joseph Stiglitz warned

there's a "significant" chance the U.S. economy will contract in the

second half of next year, and urged the government to prepare a second

stimulus package to spur job creation.

"The likelihood of this

slowdown is very, very high," Stiglitz told reporters in Singapore.

"There is a significant chance that the number will be in the negative

range."

Stiglitz, a professor at Columbia

University, called on

Washington to make more funds available to state governments who face a

drop in tax revenue. The U.S. economy, the world's largest, must grow

at least 3 per cent to create enough jobs for new entrants into the

labour force, he said.

The unemployment rate fell to 10 per cent

in November from 10.2 per cent in October.

"If

you don't prepare now, and the economy turns out to be as weak as I

think it's likely to be, then you'll be in a very difficult position,"

he said.

The economy grew at a 2.8 per cent rate

in July through September, after a record four straight quarters of

contraction.

TAPPER: Economists like Joseph Stiglitz and Paul Krugman say

that they're worried there's going to be -- the economy's going to

contract in the second half. How worried is President Obama about

a

double-dip recession?

GIBBS: Well, again, I think

-- I would say the president is worried about today and worried about

the future.

TAPPER: Does he think it's

likely? I mean, is he...

GIBBS: I -- I -- I would

simply say the president is --

wakes up concerned every day about where this economy is; understands

that millions are hurting, whether they are in last month's job losses

or the job losses stretching past those two years since this recession

officially began. But understand, people were hurting long before a

board said there was a recession in this country.

TAPPER: Right. But

obviously you plan differently if you

expect a, you know, another contraction of the economy coming up, as

opposed to the line that we're on right now.

GIBBS: Well, but I also

think that the president -- again,

I refer you back to what the president talked about in December:

him

not being satisfied with where we were and wanting to change that --

the direction of that line.

TAPPER: So he is preparing as

if there is going to be a contraction. He is...

(CROSSTALK)

GIBBS: No, no, no, no. I --

he's not an economic

prognosticator. The president is concerned about the economy;

concerned about the stories of people hurting that he has heard for

many, many years and is working to do all that we can to create an

environment for businesses, small and large, to hire more people.

TAPPER: The -- the

administration this week announced that it

was going to temporarily, at least, or for the time being suspend the

transfer of detainees from Guantanamo Bay to Yemen. You did

transfer

six in December. Are you -- do you know where those six are?

GIBBS: I'm not going to get

into -- I think Christi

(Parsons of the Chicago Tribune) asked these questions the other day

and I'm not going to get into discussing transfers.

TAPPER: OK. Given the need to

talk to Congress and get them on

board with the transfer of prisoners to the Thomson Correctional

Center, the need to convert that prison from a maximum security prison

to a super-max, do you have any realistic timetable as to when you

think Guantanamo can actually be closed?

GIBBS: I -- I think Christi

also asked that question. I

didn't have a timetable answer. Obviously, we'll work with Congress in

the upcoming session on many of the things that you talked about, not

just retrofitting, but purchasing a prison on Thomson, as well as other

issues relating to the movement of prisoners from Guantanamo to Thomson.

TAPPER: One last question, I'm

sorry. The -- in recent days,

Qais Khazali, who was a member -- the leader of the League of the

Righteous in Iraq. He was arrested by U.S. forces in 2007.

He was

responsible for an attack in Karbala that killed five U.S.

soldiers.

In recent days, the U.S. military has turned him over to the Iraqis,

and the Iraqis have freed him as part of the reconciliation going on

there.

GIBBS: I -- let me ask

somebody to...

TAPPER: I got this from the Pentagon.

GIBBS: OK. Well, let

me ask -- let me get some information on the -- on that case. I

don't have anything in front of me.

TAPPER: Well, this is a general

question: Is it appropriate for the U.S. military to turn...

GIBBS: Let me -- let me --

other than what you've told me, I'm not overly familiar with the

details of the case.

TAPPER: Just as a general

principle?

GIBBS: I don't want to --

I don't want to generalize about something with which you've just asked

me with great specificity

TAPPER: Economists like Joseph

Stiglitz and Paul Krugman say

that they're worried there's going to be -- the economy's going to

contract in the second half. How worried is President Obama about

a

double-dip recession?

GIBBS: Well, again, I think

-- I would say the president is worried about today and worried about

the future.

TAPPER: Does he think it's

likely? I mean, is he...

GIBBS: I -- I -- I would

simply say the president is --

wakes up concerned every day about where this economy is; understands

that millions are hurting, whether they are in last month's job losses

or the job losses stretching past those two years since this recession

officially began. But understand, people were hurting long before a

board said there was a recession in this country.

TAPPER: Right. But

obviously you plan differently if you

expect a, you know, another contraction of the economy coming up, as

opposed to the line that we're on right now.

GIBBS: Well, but I also

think that the president -- again,

I refer you back to what the president talked about in December:

him

not being satisfied with where we were and wanting to change that --

the direction of that line.

TAPPER: So he is preparing as

if there is going to be a contraction. He is...

(CROSSTALK)

GIBBS: No, no, no, no. I --

he's not an economic

prognosticator. The president is concerned about the economy;

concerned about the stories of people hurting that he has heard for

many, many years and is working to do all that we can to create an

environment for businesses, small and large, to hire more people.

TAPPER: The -- the

administration this week announced that it

was going to temporarily, at least, or for the time being suspend the

transfer of detainees from Guantanamo Bay to Yemen. You did

transfer

six in December. Are you -- do you know where those six are?

GIBBS: I'm not going to get

into -- I think Christi

(Parsons of the Chicago Tribune) asked these questions the other day

and I'm not going to get into discussing transfers.

TAPPER: OK. Given the need to

talk to Congress and get them on

board with the transfer of prisoners to the Thomson Correctional

Center, the need to convert that prison from a maximum security prison

to a super-max, do you have any realistic timetable as to when you

think Guantanamo can actually be closed?

GIBBS: I -- I think Christi

also asked that question. I

didn't have a timetable answer. Obviously, we'll work with Congress in

the upcoming session on many of the things that you talked about, not

just retrofitting, but purchasing a prison on Thomson, as well as other

issues relating to the movement of prisoners from Guantanamo to Thomson.

TAPPER: One last question, I'm

sorry. The -- in recent days,

Qais Khazali, who was a member -- the leader of the League of the

Righteous in Iraq. He was arrested by U.S. forces in 2007.

He was

responsible for an attack in Karbala that killed five U.S.

soldiers.

In recent days, the U.S. military has turned him over to the Iraqis,

and the Iraqis have freed him as part of the reconciliation going on

there.

GIBBS: I -- let me ask

somebody to...

TAPPER: I got this from the Pentagon.

GIBBS: OK. Well, let

me ask -- let me get some information on the -- on that case. I

don't have anything in front of me.

TAPPER: Well, this is a general

question: Is it appropriate for the U.S. military to turn...

GIBBS: Let me -- let me --

other than what you've told me, I'm not overly familiar with the

details of the case.

TAPPER: Just as a general

principle?

GIBBS: I don't want to -- I

don't want to generalize about something with which you've just asked

me with great specificity

Pretty speeches can take you only so far.

A month

after the Copenhagen climate conference, it is clear that the

world’s leaders were unable to translate rhetoric about global

warming into action.

It was, of course, nice that world

leaders could agree that it

would be bad to risk the devastation that could be wrought by an

increase in global temperatures of more than two degrees Celsius.

At least they paid some attention to the mounting scientific

evidence. And certain principles set out in the 1992 Rio Framework

Convention, including “common but differentiated responsibilities

and respective capabilities,” were affirmed. So, too, was the

developed countries’ agreement to “provide adequate, predictable

and sustainable financial resources, technology, and

capacity-building” to developing countries.

The failure of Copenhagen was not the

absence of a legally

binding agreement. The real failure was that there was no agreement

about how to achieve the lofty goal of saving the planet, no

agreement about reductions in carbon emissions, no agreement on how

to share the burden, and no agreement on help for developing

countries. Even the commitment of the accord to provide amounts

approaching $30 billion for the period 2010-12 for adaptation and

mitigation appears paltry next to the hundreds of billions of

dollars that have been doled out to the banks in the bailouts of

2008-09. If we can afford that much to save banks, we can afford

something more to save the planet.

The consequences of the failure are

already apparent: The price

of emission rights in the European Union Emission Trading System

has fallen, which means that firms will have less incentive to

reduce emissions now and less incentive to invest in innovations

that will reduce emissions in the future. Firms that wanted to do

the right thing, to spend the money to reduce their emissions, now

worry that doing so would put them at a competitive disadvantage as

others continue to emit without restraint. European firms will

continue to be at a competitive disadvantage relative to American

firms, which bear no cost for their emissions.

Underlying the failure in Copenhagen are

some deep problems. The

Kyoto approach allocated emission rights, which are a valuable

asset. If emissions were appropriately restricted, the value of

emission rights would be a couple trillion dollars a year -- no

wonder that there is a squabble over who should get them.

Clearly, the idea that those who emitted

more in the past should

get more emission rights for the future is unacceptable. The

“minimally” fair allocation to the developing countries requires

equal emission rights per capita. Most ethical principles would

suggest that, if one is distributing what amounts to “money” around

the world, one should give more (per capita) to the poor.

So, too, most ethical principles would

suggest that those that

have polluted more in the past -- especially after the problem was

recognized in 1992 -- should have less right to pollute in the

future. But such an allocation would implicitly transfer hundreds

of billions of dollars from rich to poor. Given the difficulty of

coming up with even $10 billion a year -- let alone the $200

billion a year that is needed for mitigation and adaptation -- it

is wishful thinking to expect an agreement along these lines.

Perhaps it is time to try another

approach: a commitment by each

country to raise the price of emissions (whether through a carbon

tax or emissions caps) to an agreed level, say, $80 per ton.

Countries could use the revenues as an alternative to other taxes

-- it makes much more sense to tax bad things than good things.

Developed countries could use some of the revenues generated to

fulfill their obligations to help the developing countries in terms

of adaptation and to compensate them for maintaining forests, which

provide a global public good through carbon sequestration.

We have seen that goodwill alone can get

us only so far. We must

now conjoin self-interest with good intentions, especially because

leaders in some countries (particularly the United States) seem

afraid of competition from emerging markets even without any

advantage they might receive from not having to pay for carbon

emissions. A system of border taxes -- imposed on imports from

countries where firms do not have to pay appropriately for carbon

emissions -- would level the playing field and provide economic and

political incentives for countries to adopt a carbon tax or

emission caps. That, in turn, would provide economic incentives for

firms to reduce their emissions.

Time is of the essence. While the world

dawdles, greenhouse

gases are building up in the atmosphere, and the likelihood that

the world will meet even the agreed-upon target of limiting global

warming to two degrees Celsius is diminishing. We have given the

Kyoto approach, based on emission rights, more than a fair chance.

Given the fundamental problems underlying it, Copenhagen’s failure

should not be a surprise. At the very least, it is worth giving the

alternative a chance.

Stiglitz Says Wall Street ‘Talking Up’

Recovery (Update1)

By Isabelle Mas and Simon Kennedy

Jan. 7 (Bloomberg) -- Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz

said

investors are “talking up” signs of a global economic recovery

in a bid to boost equities.

“Wall Street is talking up the recovery

because it would

like to sell stocks,” Stiglitz told reporters at a conference

in Paris today.

The MSCI

World Index of stocks has surged 73 percent since

its low of last March even while the economies of advanced

nations grow below their potential rates following the worst

recession since the Great Depression.

Stocks are rallying because interest

rates are low and

companies have been cutting costs by reducing payrolls, factors

that suggest economies remain weak, said Stiglitz, a professor

at Columbia University in New York.

“Whenever rates are low, stock markets

are often high,”

he said. By contrast, economists are “almost universally

pessimistic.”

Speaking at the conference, Stiglitz said

U.S. regulators

haven’t done enough to address the risks posed by large banks,

derivatives and executive compensation.

He recommended a tax be introduced on

financial speculation

as a way of generating revenue and forcing investors to focus on

the longer-term.

The next bubble to burst

"Find the trend whose premise is

false, and bet against it."

- George Soros

It didn't used to be this way. Back in

the days of Bretton Woods,

and

a gold-backed currency, the financial markets were relatively

stable. If you wanted to make money you had to do it over a long period

of time.

In the post-Bretton Woods era, and especially in the last

decade, market bubbles and crashes happen every few years. An investor

with a keen eye and an open mind can spot golden investment

opportunities, or at least avoid the fallout from the bubble bust.

We are about to see the bursting of the

next bubble...and its

going to be a doozy.

With President-elect Barack Obama and congressional

Democrats considering a massive spending package aimed at pulling the

nation out of recession, the national debt is projected to jump by

as much as $2 trillion this year, an unprecedented increase that

could test the world's appetite for financing U.S. government spending.

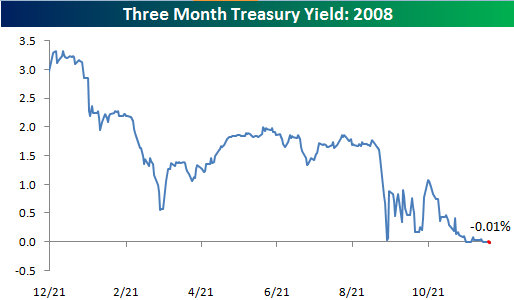

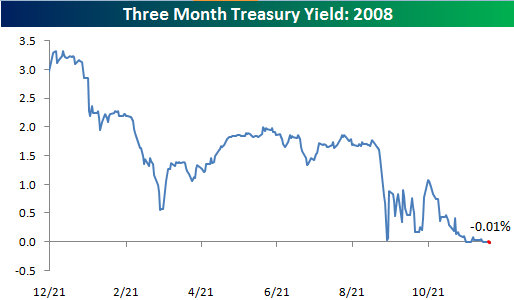

For now, investors are frantically stuffing money into the

relative

safety of the U.S. Treasury, which has come to serve as the world's

mattress in troubled times. Interest rates on Treasury bills have

plummeted to historic lows, with some short-term investors literally

giving the government money for free.

But about 40 percent of the debt held by private investors

will mature in a year or less,

according to Treasury officials. When those loans come due, the

Treasury will have to borrow more money to repay them, even as it

launches perhaps the most aggressive expansion of U.S. debt in modern

history.

You can always spot a bubble by the

irrationality of the investment

near the top. For instance, in 2005 people were offering tens of

thousands of dollars above asking price for homes because they were

"afraid they would be priced out of the market" and never be able to

afford a home.

In other words, it was

panic buying - paying premium prices for an asset irregardless of

its long-term investment value. A sure sign of a bubble.

We are seeing this same dynamic today in

treasury bonds.

It isn't just short-term treasuries. The

30 year treasury bond

yields just 2.83%. Does anyone really think that inflation in the next

30 years will never surpass 2.83%?

The flight to U.S. Treasuries

is an Armageddon trade.

It reflects investors’ panicked attempts to seek safety amid plummeting

stock markets, collapsing property values and more than $1 trillion in

losses and write-offs by banks worldwide.

There never was, and never will be,

justification for yields on any bond to be negative. What it means is

that people are paying the government to lend it money.

It makes no economic sense at all. Shoving your cash into your mattress

is a better investment than that. Like the housing bubble and the

Dot-Com bubble, this illogical panic buying will end poorly as well.

The treasury bubble isn't just a bad

investment because the

investor knowingly looses money. It's a bad investment because the

fundamentals of the asset are deteriorating.

Note the Washington

Post article above. The federal government isn't just adding $2

Trillion in new treasuries to the market this year, but another $6

Trillion is maturing this year. That $6 Trillion in existing debt will

need to be rolled over (because we have no intention of ever paying it

down). Thus we need to borrow $8 Trillion just this year,

almost all of that from foreigners (because we don't save money in

America. We spend it on imports from those same foreigners).

So then the question is: how likely are foreigners to loan us the

money? Let's look at the trend of their recent

appetite for our debt.

Net purchases of the U.S.

long-term securities

declined from $65.4 billion (revised down from $66.2 billion) in

September to 1.5 billion in October. That’s quite a disastrous result,

considering the foreign purchases barely cover the domestic sale, while

the markets expected a value close to $40 billion for October net

purchases.

It's important to note that the

treasury and the dollar are joined at the hip. Any blow to

confidence in one, hits the other just as hard. Here's a quick list of

items to look for in the coming year:

1) The global recession is forcing

nations to sell their currency

reserves (which are usually dollars) to protect their own currency.

India and Russia have already been doing this.

2) Selling treasuries are the equivalent

of promises to print money.

More dollars being printed means a weaker dollar in the future.

3) Foreign sovereign-wealth funds took a

beating in late 2007 and

early 2008 when they bought into Wall Street banks. They will be much

more cautious buying dollar assets in the future.

4) The bailouts aren't over. The states

are asking for a

$1 Trillion bailout.

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation will need a bailout this year

of tens of billions. The bailouts of AIG, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

keep getting more costly. The automakers will need more money as well.

5) The economy could be even worse than

expected, thus causing a shortage of tax revenue.

America's GDP is only about $13

Trillion. Does it sound even

remotely logical and sustainable for a nation that produces $13

Trillion a year to be borrowing $8 Trillion in a single year?

So what does it mean for the treasury

bubble to pop?

For starters, because it is a bubble, millions of investors would lose

money, which might cause a selling panic (bursting bubbles are always

messy).

Second, it might threaten

Treasuries’ status as the

global “risk-free asset” and would damage the international stature of

the U.S. Foreigners, who own about half of all Treasuries, might stop

funding the country’s growing trade and budget deficits without an

increase in U.S. interest rates.

Finally, a busted Treasury-market bubble

could undermine the

dollar’s global reserve-currency status, which in turn would spell

higher U.S. interest rates, undercutting economic growth.

Basically what I am saying is sell your

treasuries now if you have

any. They are overvalued and have nowhere to go but down, and when it

goes down it will take the dollar with it.

Story Tools

Font size:

Photo visibility:

PARIS

— Five prominent economists who correctly predicted the 2008 world

economic meltdown say the crisis is only going to get worse.

"Beware

the happy talk from those who say we are 'turning the corner,'" writes

Dean Baker of the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Economic Research.

"Ignore the daily ups and downs of the market and tighten your belts.

This is going to hurt."

Canada wasn't spared in the dire

prognostications Monday in the latest online edition of Foreign Policy

magazine.

New

York University economist Nouriel Roubini, dubbed "Dr. Doom" in an

August profile in a New York Times Sunday Magazine, said the crisis is

still in its early stages.

"As the U.S. economy shrinks, the

entire global economy will go into recession. In Europe, Canada, Japan

and the other advanced economies, it will be severe," according to

Roubini.

"Nor will emerging-market economies —

linked to the

developed world by trade in goods, finance, and currency — escape real

pain."

Roubini, who was speaking publicly about

an impending

disaster in 2006, added: "The bubbles, and there were many, have only

begun to burst."

He predicted the U.S. recession will last

at

least two years and could drag on as long as the one that plagued Japan

in the 1990s.

He said hedge funds are being forced to

sell their

assets at fire-sale prices while some financial institutions will go

bust, and some governments in emerging economies could default on their

debt.

Morgan Stanley Asia chairman Stephen

Roach said Asian

economies will suffer from being overly dependent on exports to the

U.S. and on their own undervalued currencies.

"A similar verdict

is likely for the commodity-producing regions of the world, not just

the oil-dependent Middle East, but also the resource-intensive

economies of Australia, Canada, Brazil, Russia and Africa," Roach

writes.

"As global growth slows, so does the

demand for

economically sensitive commodities, resulting in a sharp correction in

the bubble-distorted commodity prices and growth rates of the major

commodity producers."

Yale University economist Robert J.

Shiller, author of the 2008 book The Subprime Solution, was one of

several who cited the example of Japan.

"History tells us there

is some precedent for a protracted, weak housing market. After the last

housing boom in the United States peaked in 1989, it took a typical

city five years to hit bottom," he writes.

"This time, prices

have only been going down for two years. We might look with caution to

Japan, where urban land prices fell for 15 consecutive years, from 1991

to 2006."

The least pessimistic is International

Economy magazine

editor David Smick, who predicts that U.S. president-elect Barack

Obama's first budget deficit will surpass $1.5 trillion US as he faces

demands to stimulate the economy, enacts his own spending and tax-cut

initiatives, and faces a mountain of bailout demands from state

governments, private pension funds and other ailing institutions.

Internationally,

Smick said export-dependent developing countries, and the western banks

that financed their growth, are particularly vulnerable.

"If too

many of these emerging markets go down, the IMF (International Monetary

Fund) lacks the necessary resources to mount rescue operations," writes

Smick, author of the 2008 book The World Is Curved: Hidden Dangers to

the Global Economy.

"To put things in perspective, Austrian

banks

have emerging-market financial exposure exceeding $290 billion.

Austria's GDP is only $370 billion."

Smick's optimism emanates

from the oceans of cash sitting on the world economy's sidelines,

including $6 trillion in money market funds alone

"The faster

Obama and his global counterparts can fashion credible financial

reforms that enhance transparency while preserving capital and trade

flows, the sooner that sidelined capital will re-engage," he writes.

"In

the end, markets crave certainty — in this case, certainty that our

leaders have a credible game plan. That plan is not yet in place."

© Copyright (c)

The Vancouver Sun

Once again, the U.S. economy

faces disaster should we not enact more stimulus. Joseph Stiglitz has

warned that the U.S. economy could contract again in the second half of

2010 without additional government stimulus.